India–China border tensions have become one of the Indo-Pacific’s defining territorial disputes. The ongoing Ladakh crisis ended more than three decades of confidence-building measures and border agreements in June 2020 with the deaths of Indian and Chinese soldiers. Multiple rounds of tactical and diplomatic talks have resulted in a stalemate between the two Asian powers. Over the past year, there’s been a renewed build-up of military and transport infrastructure along the border as both countries reacted to tensions.

Beijing and New Delhi have attempted to manage escalation through ad hoc disengagement pacts, but heightened mistrust and growing Chinese assertiveness across the Indo-Pacific have cemented the de facto India–China border, known as the Line of Actual Control, as a flashpoint. Earlier this month, reports emerged of a fresh standoff between soldiers along the northeastern border, while the latest round of military talks failed to ease tensions in Ladakh.

The Chinese military’s activity on the contested border has been one of the key drivers behind the shift in the Indian public’s and government’s assessments of India’s relationship with China. The result has been a faster convergence in regional security and strategic policy directions. One obvious manifestation of this is the growing Quad partnership of New Delhi, Tokyo, Canberra and Washington. Events and activities on and around this contested border are important to understand, not only for regional dynamics but also because of the risk of escalation and possibly even wider conflict.

Yet, outside of a small community of defence and security researchers, there’s a lack of public understanding about the unsettled border, including historical areas of contention, strategic considerations and current developments. One key area is the Doklam region—a strategically significant territory cushioned between India, China and Bhutan but claimed by both China and Bhutan. A 2017 stand-off between Indian and Chinese troops there highlighted the ongoing risk of an unsettled border. The 2017 standoff, similar to current tensions, ended after a secretive disengagement agreement was reached.

A new project by ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre aims to help bridge this gap by assisting policymakers, practitioners and the public to better understand developments along the India–China border.

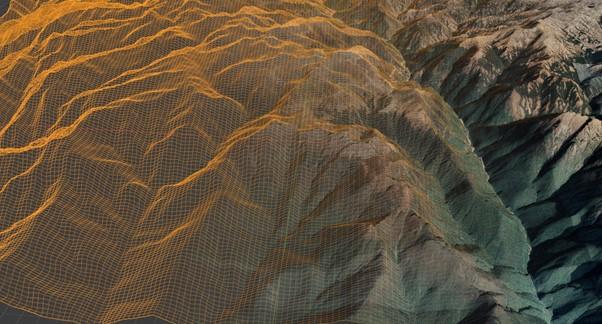

We constructed 3D models—stitched together through collection and analysis of new satellite imagery and by using open-source datasets we compiled (including geolocated military and infrastructure positions)—looking at Doklam to help assess current developments.

Our findings are set out in a visual interactive report with a 3D satellite model and a 3D topographic model. These models are overlaid with our new datasets to help explain key points of tension in Doklam.

We searched satellite imagery from 2017 to 2021 for areas of human influence and likely military positions and infrastructure, which we then marked and annotated. Archived imagery dating back to 2005 was used to establish what developments had occurred and when.

We found that India and China have both continued building military infrastructure along the border, including new frontline observation towers and forward troop bases. China accelerated construction following the 2017 stand-off, and road construction continued through late 2020 and early 2021.

In Doklam, despite the 2017 disengagement agreement, China has exploited its de facto control of Bhutanese territory, allowing its military to continue building strategic road infrastructure, including a strategic ‘rear road’, towards Indian territory. There was significant construction in 2018 and 2019, following the stand-off.

India’s historical positions along the borderlands in the Doklam region have enabled it to maintain a surveillance advantage throughout the area from frontline locations abutting the border. However, China has consolidated its position across Doklam over the past 20 years, largely building in areas hidden by terrain from Indian positions. Some of this construction has accelerated since 2017.

Approximately 50 square kilometres of internationally recognised Bhutanese territory is now under the de facto control of Beijing. The Chinese military continues to construct military positions and infrastructure in this area.

The result is a crowded border with built-up infrastructure and thousands of Indian and Chinese posts competing for strategic territorial advantage. This increases the risk of escalation and military conflict.

The disputed Doklam Plateau reflects many of the shortcomings of tactical disengagement agreements across the Line of Actual Control. While those agreements are helpful steps in reducing the likelihood of immediate conflict, they don’t address the strategic drivers of tension along the border, and several risk factors for future conflict remain. They include the physical proximity of Indian and Chinese forces, the differing perceptions of where the border lies and China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region.

Those risk factors should be mapped in detail, and both sides must make meaningful concessions if they want to lessen the likelihood of conflict. If China continues to seek to change the status quo, the escalatory risks will grow.