Barack Obama’s West Point speech shows a man tired of the presidency, weighed down by the war in Afghanistan and unsure of America’s role in the world. Obama is having his LBJ moment. Johnson fought an unpopular war, losing domestic support and ultimately the support of his party. The plain-talking Texan lamented:

Barack Obama’s West Point speech shows a man tired of the presidency, weighed down by the war in Afghanistan and unsure of America’s role in the world. Obama is having his LBJ moment. Johnson fought an unpopular war, losing domestic support and ultimately the support of his party. The plain-talking Texan lamented:

I knew from the start that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved—the Great Society—in order to get involved in that bitch of a war on the other side of the world, then I would lose everything at home. All my programs…. But if I left that war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam, then I would be seen as a coward and my nation would be seen as an appeaser and we would both find it impossible to accomplish anything for anybody anywhere on the entire globe.

Substitute Afghanistan for South Vietnam and you have Obama’s dilemma. But Afghanistan is a sideshow compared to the Vietnam War and Obama is no LBJ.

The West Point speech is a model of Obama’s foreign policy style: all equivocation-by-analysis. The President points to the different traditions of isolationism and internationalism in US strategic thinking, ‘but I believe neither view fully speaks to the demands of this moment’. He then caveats America’s commitment to world security:

The United States will use military force, unilaterally if necessary, when our core interests demand it—when our people are threatened, when our livelihoods are at stake, when the security of our allies is in danger. … On the other hand, when issues of global concern do not pose a direct threat to the United States, when such issues are at stake—when crises arise that stir our conscience or push the world in a more dangerous direction but do not directly threaten us—then the threshold for military action must be higher. In such circumstances, we should not go it alone. Instead, we must mobilize allies and partners to take collective action.

America’s enemies will read this as an invitation to meddle at the margins—Ukraine, the Senkakus, the South China Sea, Syria—the places where there’s no direct threat to the US but where global interests are on the line. America’s friends will read the same speech as meaning they must do more to protect their own interests to be treated as a serious ally.

Tony Abbott will shortly make his first visit to Washington as Prime Minister. He needs to deliver a pep talk to the despondent Obama. Abbott diagnosed the problem 18 months ago on his last visit to DC as opposition leader. Then, he addressed the conservative Heritage Foundation:

What’s remarkable right now is that, perhaps for the first time, the world appears to have more confidence in America than America does in itself. … These are new and testing circumstances, perhaps more testing than any since the end of the Cold War, but that just makes despondency, let alone defeatism, more corrosive than usual.

Spot on, Prime Minister. Abbott and Obama might not be the most obvious pairing: the feisty, instinctive Oxford boxing Blue and the cool, analytical Harvard Law School grad don’t share many connections. So what should the Prime Minister and the President say to each other about the bilateral relationship?

Abbott should say to Obama that Asia is fretting about Washington’s malaise; that China has moved to a new level of on-the-ground pushing to achieve its aims; that America needs to square its shoulders and present a harder-edged presence in the region. Abbott should point to his recent increases in defence spending; remind the President about our willingness to take the fight to the enemy in Afghanistan and the enhanced cooperation agenda with the Marines and USAF in northern Australia; and say that Australia is ready to look at opportunities for expanding military cooperation with the US on space, cyber, BMD, Special Forces and ASW (among other things).

For his part, Barack Obama may want reassurance that Australia is genuine about enhancing defence cooperation. Why should Washington take anything we say for granted when it’s clear from Bob Carr’s diary that he wasn’t signed up to closer cooperation and more concerned about Beijing’s view? Obama should ask why hasn’t Australia done a better job of demolishing the ‘China choice’ red herring.

In short, both leaders need to size each other up and decide how genuine they are about defence cooperation. A tough conversation like this would best be done away from the cameras, with sleeves rolled up, shooting hoops in the presidential gym. That could build a personal connection between PM and President, and a platform for necessary innovation in defence ties over the next few years.

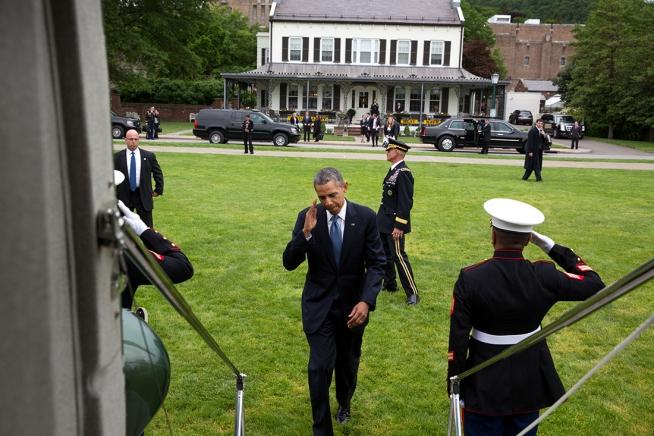

Peter Jennings is executive director of ASPI. Image courtesy of the White House.