On 8 July, the world was stunned by the assassination of former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe during a campaigning speech in the city of Nara two days before elections were to take place. While domestic debates about improved security for politicians continue in Japan, it’s also timely to reflect on the legacy of Abe’s achievements in terms of not only his foreign policy legacy, but, especially for Australians, the contribution he made towards strengthening Japan–Australia ties.

It was during his first term in office (2006–07) that Abe signed the foundational Japan–Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation with Australian PM John Howard—a moment that redefined the whole nature of bilateral ties by extending economic and diplomatic cooperation to the security and defence spheres.

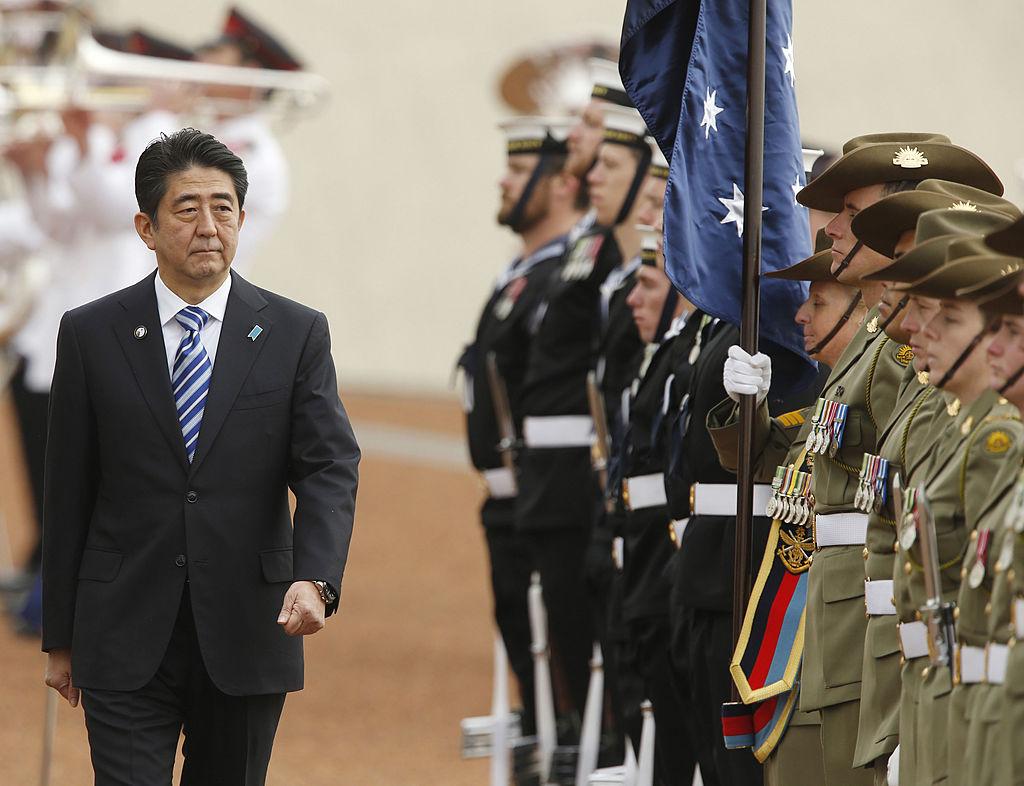

When Abe returned to office for his second term in 2012, he lost no time in further consolidating that earlier achievement. When he again visited Australia to address parliament in July 2014, he jointly launched the so-called special strategic partnership with then PM Tony Abbott. Both Abe and Abbott concurred at the time that a ‘special relationship’ was born that day. This was very specific qualitative language, reserved only for the closest of partnerships, and most commonly associated with descriptions of US–UK or US–Israel ties. Prior to this, in 2013, Abbott had already described Japan, not without controversy, as Australia’s ‘best friend in Asia’.

But the 2014 special strategic partnership announcement was more than simply effusive rhetoric and public diplomacy optics. It was accompanied by the launch of the Japan–Australia Economic Partnership Agreement, the most significant step forward in bilateral economic relations since Abe’s grandfather PM Nobusuke Kishi signed the Australia–Japan Agreement on Commerce in 1957. The 2014 agreement has since overseen increased economic cooperation; an uptick of more than 30% in two-way trade; and the development of infrastructure projects, such as the Ichthys LNG facility in northern Australia, supported by Japanese company INPEX, which is vital to the export of energy supplies to Japan.

The 2014 visit also resulted in the signing of an agreement for transfers of defence equipment and technology, designed to facilitate closer defence-technological collaboration. Though Canberra did not pursue cooperation on submarines with Japan as originally envisaged, it’s likely that this agreement will be the basis for plans to explore other high-technology projects such as, potentially, joint missile procurement.

Under Abe, Japan and Australia worked hand in glove to coordinate efforts to strengthen the regional architecture in the Indo-Pacific with the shared aim of building a stable, prosperous and rules-based order. During the turbulent presidency of Donald Trump in the US, they worked together to rescue the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which now lives on as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership under their combined leadership. Abe was also pivotal in reviving the Japan–Australia–US–India Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, which has since gone from strength to strength and forms a major platform for combined regional engagement.

Japan’s move towards a more prominent role as a regional security actor under Abe’s banner of a ‘proactive contribution to peace’ and the ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ vision, launched by Abe in 2016, were also well received in Canberra. Indeed, Australia has effectively adopted the latter concept, alongside others including the United States, to frame much of its regional engagement and to uphold a rules-based order.

Under Abe, real practical cooperation in the security and defence sphere progressed. Upgrades to logistical arrangements under the acquisition and cross-servicing agreement were put in place, followed shortly after Abe’s departure from office by the long-awaited reciprocal access agreement, which allows for smoother operational cooperation between the Australian Defence Force and the Japan Self-Defense Forces to train and exercise in one another’s countries, something he paved the way for. Even more significantly, it was Abe who pushed through ground-breaking domestic legislation in a package of peace and security laws in 2015, which created provisions for the right to ‘collective defence’ and now allows the Japan Self-Defense Forces to protect Australian deployments in the event of a survival-threatening situation.

Abe was also a champion of historical reconciliation with Australia, making an unprecedented prime ministerial visit in 2018 to Darwin, the site of sustained aerial attacks by the Empire of Japan during the Pacific War in 1942 and 1943. The visit was a part of his bid to move beyond past animosities and form the basis for a future-focused relationship—at the time, he declaimed: ‘We in Japan will never forget your openminded spirit nor the past history between us.’

There were frictions and disappointments in bilateral ties during Abe’s terms of office, such as the Australian case against Japan over whaling in the International Court of Justice, and Tokyo’s surprise at being eliminated from the tender for Australia’s future submarine program in 2016 (in favour of the French contract, since annulled and replaced by AUKUS). Yet, these setbacks were successfully absorbed and have not had a significant lasting impact on the relationship.

The tragic loss of Abe has been deeply felt in Canberra and elsewhere. After Abe’s death, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese praised him as a ‘true leader and true friend’ to Australia, a sentiment echoed by Abbott, who called Abe a ‘best friend of Australia’.

Abe’s determined leadership played a crucial role not only in charting a new path for Japan but also in building the strategic partnership with Australia. Thanks to the special strategic partnership bequeathed to us by Abe, a recent study by the Australian National University concluded that ‘Australia’s relationship with Japan has never been more close.’ Under the partnership, Japan and Australia now cooperate across a wide spectrum of diplomatic, security, defence, military, economic and scientific areas on a scale and at a pace never seen before. This in large part can be credited to the far-sighted leadership of Abe, in tandem with his Australian counterparts.

As Abe himself exhorted the Australian parliament back in 2014 in one of his many colourful evocations: ‘Let us walk forward together, Australia and Japan, with no limits.’ His successors in Tokyo and Canberra appear to have every intention of continuing on the path of bilateral friendship and cooperation that Abe did so much to pioneer.