Abu Sayyaf and terrorism in the southern Philippines

Posted By John McBeth on May 11, 2016 @ 14:30

When Washington dispatched a joint special operations task force to the southern Philippines in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, it was motivated by evidence that the Abu Sayyaf (ASG) militant group had links with Al Qaeda and was expanding its influence beyond the immediate region.

When Washington dispatched a joint special operations task force to the southern Philippines in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, it was motivated by evidence that the Abu Sayyaf (ASG) militant group had links with Al Qaeda and was expanding its influence beyond the immediate region.

Backed by helicopters and drones, the 600-strong force may have been there in little more than an advisory and training role, but it was one effective way of demonstrating to Americans that its government was responding to the worst terrorist assault on US soil.

In the end, the unit stayed until 2014, but sources familiar with the mission now say it was never aimed at destroying the ASG, only at degrading it to a point where US citizens and interests in the southern Philippines were no longer under threat.

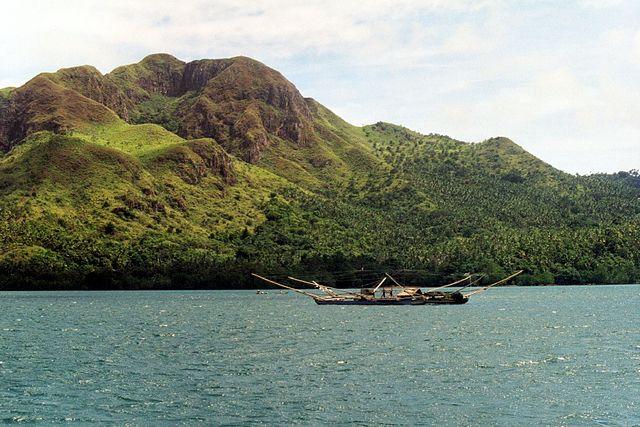

Whether that was accomplished is a now point of debate after a Jakarta shipping firm last week paid a US$1 million ransom to free 10 Indonesian crewmen who had been abducted from a tugboat [1] towing a coal barge through the Sulu Sea. Another four Indonesian and four Malaysian sailors are still being held by what’s believed to be the same al-Habsy Misaya faction of ASG, which operates from Tapul island, lying halfway between the island provinces of Tawi-Tawi and Sulu.

The case had taken on new urgency after a separate Abu Sayyaf gang beheaded a Canadian mining executive [2], seized along with a second Canadian and a Norwegian from a marina in Davao, 595 kilometres to the east of Sulu, last September.

If the Indonesians had ever contemplated a rescue mission, they would have been confronted with a baffling range of complexities, all centering around the way the ASG’s motives and affiliations are tied up in the often-bloody turbulence of southern Philippine politics.

As much as it trumpets its allegiance to the Islamic State of Syria and Iraq [3] (ISIS), only one ASG faction—on Basilan Island to the northeast of Sulu—appears to have direct links to the extremist group, and few if any Filipino militants are among the hundreds of Indonesians and Malaysians fighting in the Middle East.

Back in the early 2000s, US intelligence officers knew very little about the extent of ASG’s connections to Al Qaeda. Even today they have serious reservations about what constitutes links to ISIS, apart from militants waving its familiar black flag.

It’s certainly doubtful [4] whether any of the disparate gangs that make up ASG take orders or are receiving material or financial support from ISIS Central. The presence of foreign fighters over the years, including a Moroccan killed on Basilan recently, doesn’t prove much either.

In fact, Islam now plays an increasingly peripheral role in the ASG’s activities, which these days are more focused on kidnapping for ransom than bombings and other outright terrorist attacks. In other words, it’s back to business as usual in one of Asia’s most lawless regions.

The Indonesian Government refused to pay the ransom for the 10 sailors, but said it wouldn’t stop the tugboat owners from doing so. That’s similar to 2011 when the Samudera shipping line paid US$3 million [5] to secure the release of a bulk carrier and its 20-man crew off the coast of Somalia.

In that case, a 1,000-strong combined services task force sent to the Horn of Africa did actually intervene when a second group of pirates sought to seize back the ship after the original abductors had left with the ransom.

Indonesia’s only previous rescue mission was in March 1981 when Special Forces commandos stormed a hijacked Garuda Airlines plane [6] at Bangkok’s Don Muang International Airport and freed its 53 passengers and crew.

Mindanao presented a whole new challenge. While an Indonesian intelligence team was embedded with Philippine troops on Sulu, a rescue this time would have been extremely difficult in such an uncontrolled environment.

Indeed, a range of local sources claim there are ties between al-Habsy Misaya and Sulu Vice-Governor Abdusakur Tan, who unsuccessfully ran against incumbent [7] Mujiv Hataman for the governorship of the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) in the May 9 elections.

That has led to speculation that the taking of the Indonesians and Malaysians—and a surge in unreported abductions of wealthy businessmen across the wider region—were aimed at raising election funding for Tan and other politicians.

A Chinese Tausug, Tan is no stranger to violence. In mid-1990, forces loyal to the then-congressmen and his uncle, Saud Tan, the mayor of the Sulu capital of Jolo, fought a pitched battle with mortars and heavy machineguns against the followers of Vice-Governor, Kimar Tulawie.

By the time the Philippine Marines intervened from their hilltop base overlooking Jolo, the fighting had claimed more than 20 lives, destroyed an 800-metre swathe of the ramshackle city centre and left more than 800 people homeless.

The Abu Sayyaf was not around then and the ARMM, created only a year earlier by binding together western Mindanao’s five mainly Muslim provinces, was still struggling to get off the ground. In many respects, it still is.

What made the latest round of kidnappings a more serious escalation was the pressure being put on the Philippine government to allow the Indonesian and Malaysian governments to take direct action to intervene.

No one thinks that would have been a good idea, particularly at a time when the Philippine Army is still reeling from the loss of 18 soldiers [8] last month in a single 10-hour firefight on Basilan island.

But if ASG is not the threat it once posed as an Al Qaeda beachhead in Southeast Asia, Indonesian and Malaysian officials are increasingly worried its piratic raids could turn the Sulu archipelago into another Somalia.

That has led to Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines agreeing to mount joint patrols [9] along the Sulawesi-Sulu corridor, which carries an estimated 18 million people and 55 million tonnes of cargo a year.

But whether those patrols expand into a much bigger sea-lane—the one running through the disputed waters of the South China Sea to the west—is a completely different question.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /abu-sayyaf-and-terrorism-in-the-southern-philippines/

URLs in this post:

[1] abducted from a tugboat: http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/560649/news/world/abu-sayyaf-abducts-10-indonesian-sailors

[2] beheaded a Canadian mining executive: http://globalnews.ca/news/2660817/canadian-hostage-john-ridsdel-executed-in-philippines-after-ransom-deadline-passes/

[3] allegiance to the Islamic State of Syria and Iraq: http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2016/04/12/afp-isis-abu-sayyaf-basilan-clash.html

[4] certainly doubtful: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/inquirer/philippines-jungle-militants-eye-islamic-state/news-story/a258aca515e6ea9d062558c8ecc3c8ee

[5] Samudera shipping line paid US$3 million: http://en.tempo.co/read/news/2016/04/07/314760534/No-Deals-With-Abu-Sayyaf

[6] stormed a hijacked Garuda Airlines plane: http://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/29/world/hijackers-force-indonesian-plane-with-57-to-thailand.html

[7] who unsuccessfully ran against incumbent: http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/782579/sulu-vice-gov-tan-revels-in-support-in-armm-but

[8] loss of 18 soldiers: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36008645

[9] agreeing to mount joint patrols: http://thediplomat.com/2016/05/indonesia-philippines-malaysia-agree-on-new-joint-patrols-amid-kidnappings/

Click here to print.