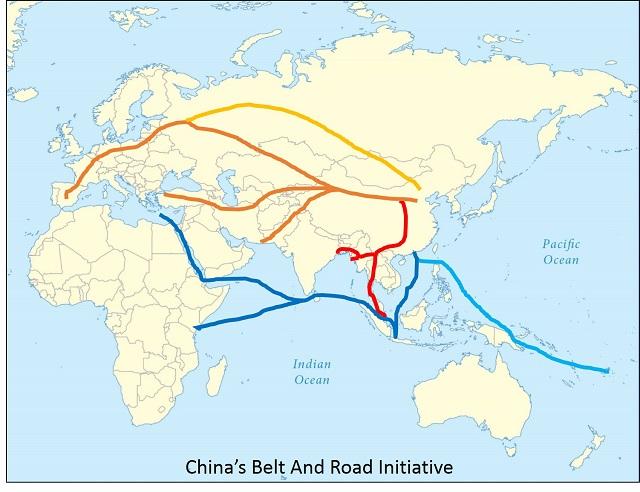

President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has caused much discussion about China’s vision for engaging the world economically. In many ways, it can bring ‘win–win’ opportunities for China’s economic partners, but there’s also potential for less desirable, unintended consequences arising from this ambitious plan.

China’s rise has seen its footprint of personnel and commercial interests overseas expand at a bewildering pace over the past two decades. Many Chinese continue to leave their shores in search of wealth and resources, either as individuals or as members of large commercial organisations. Chinese communities overseas, estimated at 35 million nine years ago, have become valuable assets in connecting China to the outside world, but they are also a potential liability. While this growing presence and influence can develop strategic interests beyond the original design, a growing subset of them are increasingly at risk from natural disasters, breakdowns of civil order, acts of terrorism, and exposure to war zones.

This growth in overseas Chinese communities has been accompanied by the continued expansion of military capability to protect China’s interests abroad and the development of a substantial middle class that expects the Communist Party to protect the Chinese diaspora. Such a development of risk accompanied by the means and expectation to address it generates a perceived obligation to act in self-defence overseas.

China’s first declared overseas military base, in the port of Obock in Djibouti, is an example of what can follow the development of commercial interests. The base will support counter-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden, enable China’s deployment of combat troops on peacekeeping operations on the African continent, and provide protection for Chinese oil imports from the Middle East at a strategic node in the BRI.

This combination of trends in growth, interests, capability and obligation is demonstrated by the recent phenomenon of Chinese evacuation operations. Referred to in China as ‘overseas citizen protection’, they have been conducted since 2006. At the turn of the century, China didn’t have the capacity, or policy, to conduct evacuation operations, and seemed content to ask other countries to evacuate its citizens.

In 2004, when 14 Chinese workers were killed in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the domestic reaction caused China to review its overseas citizen protection system, acknowledging that large numbers of Chinese were living in high-risk environments overseas. China started to conduct small evacuations using civilian means to extract citizens from Solomon Islands, Timor Leste, Tonga and Lebanon in 2006, Chad and Thailand in 2008, and Haiti and Kyrgyzstan in 2010.

The largest evacuations occurred in 2011, during the Arab Spring uprisings, when China retrieved 1,800 citizens from Egypt, 2,000 from Syria and 35,860 from Libya, along with 9,000 from Japan after the Tohoku earthquake. The 48,000 Chinese evacuated in 2011 were more than five times the total number evacuated between 1980 and 2010.

This was the first such operation to significantly involve the PLA in more than decision-making and interagency coordination in Beijing, providing surveillance, deterrence, escort and evacuation by air in the operation itself.

More recently, between 30 March and 2 April 2015, a Chinese flotilla of three PLAN naval vessels was diverted from its counter-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden to evacuate Chinese citizens from the port of Aden in Yemen. Some 563 Chinese citizens and 233 foreign citizens of 13 other nationalities were evacuated by the PLAN to Djibouti.

This was a significant development, as it was performed exclusively with military assets and was the first time the PLAN had evacuated citizens of other countries.

According to one analysis, the requirement to protect nationals abroad is much more likely to cause Chinese foreign policy to become interventionist than the protection of energy interests, largely because of public and government attention. There’s a risk that as China acts to protect its interests in areas perceived as of lesser strategic priority, such as the Southwest Pacific, its actions will generate unintended second and third order effects, with undesirable strategic consequences. This possibility has been referred to as ‘accidental friction’.

There’s evidence of an anti-Chinese mindset in Melanesian societies, associated with a belief that the ‘new Chinese’ are taking away local jobs. This perception is reinforced by negative media coverage of Chinese commercial ventures in the Pacific. Such tensions occasionally boil over into anti-Chinese violence, such as that seen in Solomon Islands and Tonga in 2006 and PNG in 2009. However, public and government opinion in China is not always sympathetic to the Chinese who are targeted in these riots.

Given the potential for anti-Chinese riots in the South Pacific, the requirement for Chinese ‘overseas citizen protection’ may become a reality in Melanesia in the near future.

If Australian and Chinese military contingents were to find themselves involved in an evacuation operation in a difficult or threatening environment, and without prior preparation, the consequences may be undesirable. A lack of understanding of each other’s techniques, control measures and rules of engagement could be quite dangerous to all involved. Such unintended consequences could be mitigated by engaging, understanding and cooperating well before this happens.