The recent geopolitical history of Afghanistan can be divided into five phases. But now it is at the cusp of another transition and the defining features of the new phase remain to be seen.

During the first phase, from 1974 to 1979, Pakistan began to give refuge and training to Islamists who could be deployed against Mohammed Daoud Khan’s government. Then, from 1979 to 1989, Pakistan, the United States, and Saudi Arabia financed, trained and equipped the mujahidin who fought against Soviet troops. From 1989 to 1996, Afghanistan was in transition as regional warlords gained power, closed in on Kabul and overthrew President Mohammad Najibullah. From 1996 to 2001, the Taliban government ushered in a period of wanton savagery and—with the exceptions of Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—diplomatic isolation.

The fifth phase began in 2001, following the 9/11 attacks. Since then, the US has been embroiled in a war supporting a patchwork Afghan government against a resurgent Pakistan-backed Taliban. The sixth phase raises two questions: did the US lose the war in Afghanistan and, if so, why?

The answer to the first question is both yes and no. The US has failed to eliminate the Taliban from Afghanistan and entirely rule out the possibility of the country again becoming a haven for terrorists. The ongoing peace talks with the Taliban and the impending reduction of the US military presence in the country are a clear recognition of this. The American public is war-weary and President Donald Trump is keen to declare an end to the longest international conflict in US history before the 2020 presidential election.

At the same time, the US achieved many of its initial core objectives. The Taliban was expelled from Kabul and, despite the current peace talks, its uncontested return remains doubtful. Osama bin Laden was killed in neighbouring Pakistan, Taliban leader Mullah Omar died in hiding, and his successor, Mullah Akhtar Mansour, was killed by a US drone strike in Pakistan in 2016. A semblance of a functioning state—including a national government and a military—is now a reality, however flawed. And Pakistan remains under pressure to clean up its act.

But, overall, things did not go according to plan for the US, for four main reasons. First, and most obviously, it made political mistakes, born largely of ignorance and hubris, although often apparent only in hindsight. After 2001, the US imposed on Afghanistan a presidential-style government with inadequate checks and balances. After 2003, policymakers became distracted by the initially more intense conflict in Iraq and withdrew resources and attention from Afghanistan. Moreover, they paid insufficient attention in the early years to building up the Afghan National Security Forces. In addition, democratisation efforts were mostly top-down rather than bottom-up, and elections often were scheduled before the appropriate political institutions were in place.

The second set of mistakes were military in nature. After 2008, US war planners believed that a counter-insurgency approach would work. But a ‘surge’ of the kind that initially reduced violence in Iraq failed in Afghanistan for a number of reasons.

For starters, the US was unable to co-opt key adversaries, as it had done with Sunni militias in Iraq following the ‘Anbar awakening’. Moreover, it had no solution to cross-border havens in Pakistan, from which Taliban forces could plot and launch continued attacks, and it underestimated the governance challenges in Afghanistan, which had much deeper roots than in Iraq and made development and state-building more difficult. And when US President Barack Obama announced the surge in Afghanistan, he undermined the effort by also setting out a withdrawal timeframe. That was a mistake that even Trump was wise enough to avoid.

The US also failed to learn from its mistakes. Comprehensive reviews of its Afghan policy that produced unpalatable or ineffective recommendations gave way to comprehensive reviews that produced equally unpalatable or ineffective outcomes. In particular, successive US administrations, military commanders and diplomats believed that buying Pakistan’s tactical cooperation through threats, aid or military support could prove sustainable. The unwillingness to address Pakistan’s support for terrorism head-on was driven by US concerns—real or inflated—about that country’s nuclear-weapons program. As a result, for years, many US policymakers persuaded themselves that the key to peace in Afghanistan lay in pressuring India to resolve the Jammu and Kashmir dispute and thereby somehow allay Pakistani insecurities.

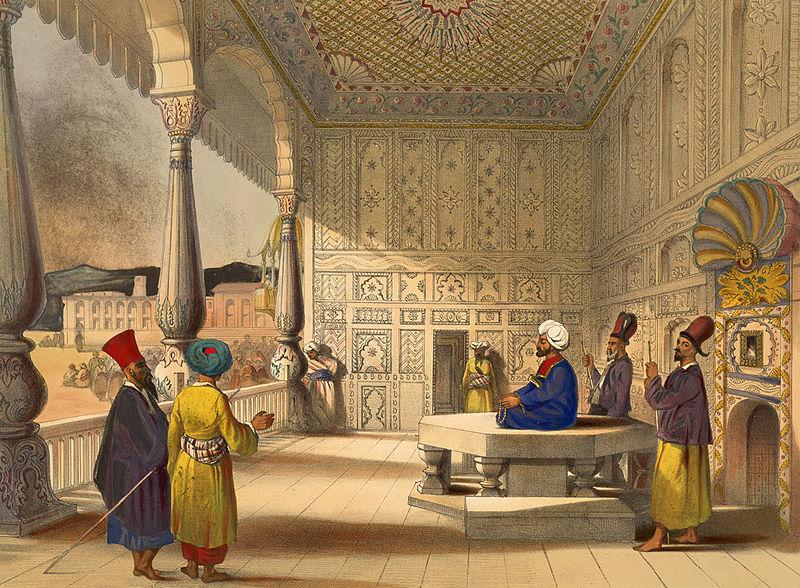

Finally, the US fell victim to its own propaganda. Consider, for example, the notion of Afghanistan as the ‘graveyard of empires’, which reflected Britain’s effort in the late 1800s to explain its failures in the First Anglo-Afghan War and the emergence of Afghanistan as a buffer zone between the British and Russian empires. It was later propagated by the US, Pakistan and others in the 1980s and the notion went hand in hand with support for the anti-Soviet Afghan mujahidin. But the reality is that Afghanistan (or parts of it) had at various points been part of the Kushan, Hellenistic, Persian, Mughal and Sikh empires, and was at the centre of the Ghaznavid and Durrani empires.

Given its location at the crossroads of Asia, Afghanistan will remain of interest to Iran, Russia, China, Pakistan and India. And as long as terrorist groups can train and operate internationally from Afghanistan and Pakistan, the US and Europe will also have a continued interest in the country’s future. In assessing that future, it will be important to reflect upon the recent past, in order to break the cycle of unlearned lessons that has brought Afghanistan and its interlocutors to this point.