The Australian government recently donated $40 million to assist with alleviating the food security and economic crises unfolding in Afghanistan, while reiterating its condemnation of the Taliban’s repression and exclusion of women and girls from education and work. Many nations have withheld donations because of these violations of human rights—as well as the revenge executions and disappearances of ‘traitors’ who worked with US-led forces and the US-backed Afghan government or criticised Taliban policies—to avoid legitimising the Taliban’s rule.

The commitment to oppressing women is, however, evidently still more important to the Taliban leadership than basic food security, despite their having a front-row seat to watch the humanitarian crisis play out and affect all Afghan society, not just women.

Surely the international community knows this calculus by now. The most significant difference between the Taliban of the 2020s and 1990s seems to be that instead of banning the internet as part of their strategy to control the population, they are savvy about the potential for a curated social-media presence to affect international perceptions and promote disinformation domestically for political and security purposes.

Australia did the right thing in making its decision based on the immediate food security needs of Afghans. This is a hugely complex situation, and the Afghan people stand to suffer even more if the international community applies too much pressure on particular issues at particular times. Intersecting security issues also make it impossible for the international community to get it right—if that’s defined as finding an option that causes no harm.

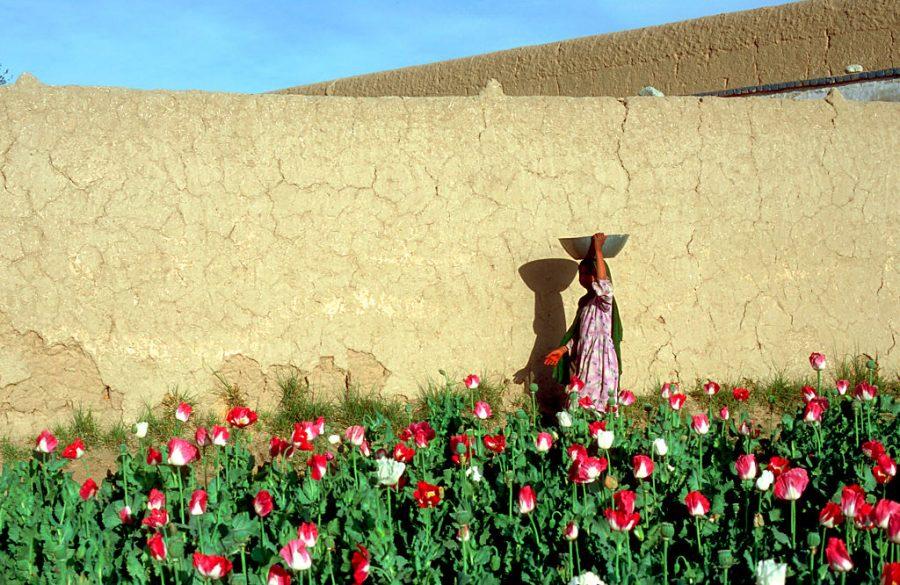

The recent ban on opium cultivation in Afghanistan responds to one of the big demands of the international community since the Taliban retook the country last year: drug control. This issue is the perfect storm of intersecting internal problems and external demands.

The particular vulnerability of the Afghan people in the wake of the US and allied withdrawal means their net benefit must remain the guiding principle for the international community’s approach to drug control, even if that brings costs or challenges there or at another place in the global heroin supply chain.

Afghan opium supplies approximately 80% of all users globally.

The 2021 harvest in Afghanistan yielded enough opium to produce 320 tons of pure heroin. For context, if that amount were sold on the Australian market (at the standard price of $50 per 0.1 gram), it would be worth $145 billion, and that’s not including the huge increase in value that we know occurs as drugs travel internationally from the farmgate to the end user. It’s also 350 times the amount of heroin Australians are known to have consumed in 2021. The potential global health costs and criminal profit from the Afghan opium yield are huge.

But a law enforcement policy that takes away a major source of income must be accompanied by an aid and development strategy to replace that income with sustainable, viable options. Otherwise, the policy is unsustainable and vulnerable people will starve.

In Afghanistan, more than 70% of people live in rural areas and around 80% of livelihoods depend on agriculture. The severe drought that decimated crops and grain stores in 2021 shows no signs of abating.

A huge portion of these agriculture-dependent livelihoods are reliant on the opium economy. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime put the value of that economy (local consumption and exports) at 9% to 14% of GDP in 2021, compared with the estimate of 9% for officially recorded legal exports of goods and service in 2020. Opium alone brings at least as much money into Afghanistan as the entire licit export economy.

The country’s ongoing drought makes identifying alternatives even more challenging. Wheat and fresh produce, for example, provide much lower returns and have much higher water requirements than opium poppies.

What options will opium farmers have as food insecurity worsens and the images of people holding desperately onto the wheels of departing aeroplanes fade further from the memory of the international community?

Enforcing a ban like this in a large, infrastructure-sparse country would be challenging at the best of times from a purely logistical perspective. But how will it be enforceable in the context of a population 95% of whom already have insufficient food every single day?

This is in stark contrast to the success of Thailand’s opium crop-replacement program, which took a development instead of a law enforcement approach. Efforts focused on enhancing food security, providing alternative crops (such as coffee) and thereby sources of income, and increasing government services in remote and rural areas.

If the international community knows the Taliban won’t budge on their treatment of women and perceived traitors, then it can’t both withhold life-saving humanitarian aid on that basis and demand an end to the opium industry that puts food on the table in many of the country’s farming communities—especially not after another catastrophic, failed nation-building attempt by Western nations. Taking a stand for women’s rights means little if it requires condemning them to starvation.

Illicit drugs are never just a law enforcement issue. In Afghanistan’s case, there’s a large humanitarian component that must be addressed in an appropriately coordinated response if the opium ban is to have any chance of success.