Alan Moorehead’s Gallipoli

Posted By Ann Moyal on May 16, 2015 @ 08:00

There have been at least seventy books by individual authors published under the title Gallipoli in as many decades. From the British Poet Laureate John Masefield in 1916 to Australia’s Les Carlyon in 2001 and on to Peter FitzSimon’s vast populist saga of 2014, they have collectively left no stone, landmark, battle, strategy, leader, fighters, gains, defeats, or lived experience unturned. Yet, for me, none can surpass the masterly, elegiac, and widely interpretative Gallipoli published by Australian expatriate, Alan Moorehead, in London in 1956 and reissued in many editions and several translations until today. Why?

A former journalist of the Melbourne Herald who left Australia in 1936 for wider scenes, Moorehead was acclaimed the Daily Express’ ‘Prince of War Correspondents’ for his cover of the British campaign in North Africa and his reporting of the war in Europe, topics he turned into his two books: African Trilogy and Eclipse. Settled in Tuscany in the post-war, he wrote twenty more books including his brilliant The White Nile, The Blue Nile and Cooper’s Creek. None, however, surpassed Gallipoli.

Yet, as an Australian schoolboy exposed to the medals in the school’s corridors and the annual talks in the memorial hall, Moorehead had come to hate the story of Anzac. As a member of the next generation, ‘we thought all these old men boring’, he wrote and when he left Australia, he swore that he ‘would never think again or expose myself to the idea of Anzac and Gallipoli’.

But after the war, when shown a diary of the campaign by an English friend, he was ‘absolutely captivated’ and gathering the private papers of British and Australian soldiers, studying the historical sources, and rounding up military archives and maps specially prepared for him by the Turks, he toured the Gallipoli Peninsula. He then became aware that ‘there could be no other story like it’ andretired to the Greek Island of Spetses in the Aegean Sea to write.

Alan Moorehead’s long first-hand experience of battle, his feeling for the soldiery, his overarching perception of policy and planning of the contributing role of international participants—the British, Irish, French, the Imperial Indian, African, and Anzac troops—together with his calm evocative style and analytical skills, placed him in the forefront of other writers.

‘A strange light plays over the Gallipoli landing on 25 April 1915’, he wrote,

‘Hardly anyone behaves on this day as you might have expected him to do. There was a certain clarity about the actions of Mustafa Kemal on the Turkish side, but for the others the great crises of the day appear to have gone cascading by as though they were some natural phenomenon, having a monstrous life of its own. For the soldiers in the front line the issues were, of course, brutally simple. Confronted by some quite impossible objective, their lives suddenly appear to them to be of no consequence at all; they get up and charge and die’.

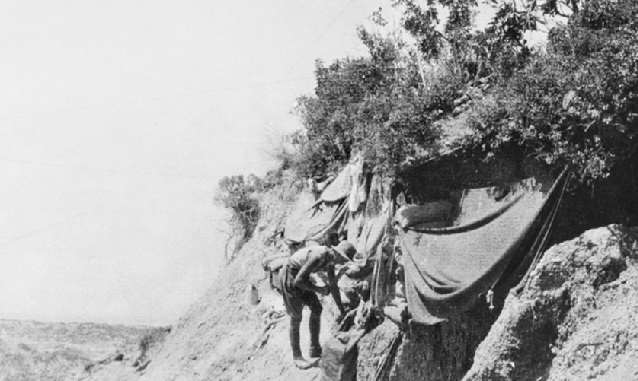

As with his World War Two despatches, there is an urgency and compelling presence in Moorehead’s descriptions of the hard-fought battles and of ‘the ant heap life’ of the soldiers: breathing, eating, sleeping, climbing, fighting, dying and burying their dead.

‘They were not fatalists’, he contends. ‘They believed that a mistake had been made in the landing at Gaba Tepe and that they might easily have to pay for it with their lives’ But there was ‘an extraordinary cheerfulness and exaltation’ among the men at the frontline. Living with the prospect of death, all the normal anxieties and jealousies of life deserted them, ‘the past receded, the future barely existed, and they lived as never before upon the moment, released from the normal weight of human ambitions and regrets’. And with his painterly eye, he observes, there were always ‘the recurring moments of release and wonder at the slanting luminous light in the early mornings and the evenings, in the marvellous colour of the sea’.

With its wide analysis, his sense of its ‘hesitant leaders, its lack of coherent planning and its fierce losses on both sides’, Moorehead cast the Gallipoli campaign in a strikingly positive light. He didn’t see it as a blunder or a reckless gamble, but as ‘the most imaginative conception of the war’ with potentialities almost beyond reckoning. Militarily its influence, he believed, was enormous. ‘It was’, he wrote, ‘the greatest amphibious operation which mankind had known up till then’ and it took place in circumstances where ‘everything was experimental’. This included the use of submarines and aircraft, the trial of modern naval guns against artillery on the shore, the manoeuvres of landing armies in small boats on a hostile coast, the use of radio, the aerial bomb, the land mines and much more. Importantly, in itself, Moorehead saw this highly complex combined operation by land, sea and sky (unlike the battles in France) as providing a practical and far reaching basis and understanding for the Allied victory of World War Two. ‘The old men were right’, he concludes, ‘it was the military event of the century’

Moorehead’s Gallipoli riveted world attention and won a number of British literary prizes including the inaugural Duff Cooper Memorial Prize for which the winner could nominate the award’s presenter. He chose Winston Churchill whose original planning of the Dardanelles campaign he had come to respect. In turn, Churchill wished the author a much greater success with the book than he had had with the campaign.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /alan-mooreheads-gallipoli/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: https://aspistrategist.ru/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/awm.png

Click here to print.