It’s rare for a public opinion survey to shake established perceptions of a country in the way a recent Pew Research Center study of religion in India has done. The revelations in Pew’s comprehensive survey, based on interviews with 30,000 adults in 17 languages between late 2019 and early 2020, have astonished many.

In particular, this nationwide, multi-faith study finds that Indians value both religious tolerance and coexistence, on the one hand, and religious exclusivity and segregation, on the other. But this apparent contradiction is in fact not entirely surprising.

For over 25 years—notably in my 1997 book India: from midnight to the millennium and beyond—I have argued that India isn’t a melting pot like the United States. Rather, it’s a thali—a collection of different dishes in separate bowls that don’t necessarily flow into one another, but nonetheless combine satisfyingly on your palate. Pew’s study, titled ‘Religion in India: tolerance and segregation’, appears to confirm my hypothesis.

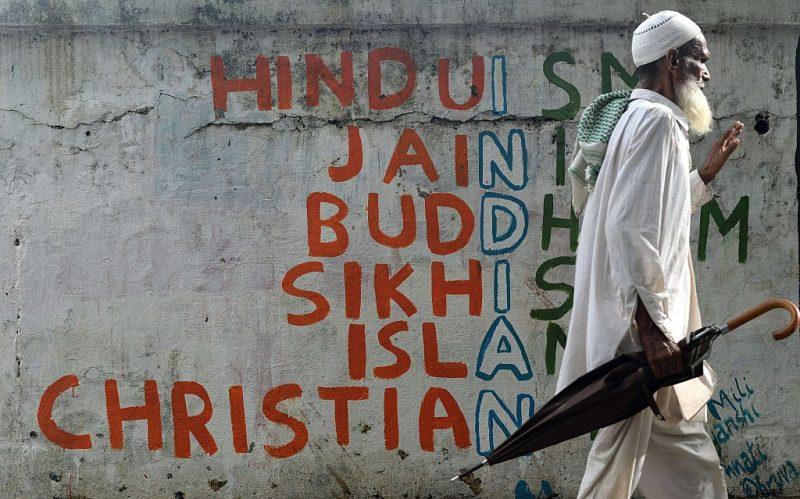

For starters, India is deeply religious: 97% of Indians say they believe in God and about 80% are certain that God exists. ‘Not only do most of the world’s Hindus, Jains and Sikhs live in India, but it also is home to one of the world’s largest Muslim populations and to millions of Christians and Buddhists,’ the Pew study observes. ‘Indians of all these religious backgrounds overwhelmingly say they are very free to practice their faiths.’ Some 53% of adults say religious diversity benefits India.

An overwhelming majority (84%) of respondents say that respect for other religions is a fundamental aspect of their identity. ‘Indians see religious tolerance as a central part of who they are as a nation,’ say the study’s authors. ‘Across the major religious groups, most people say it is very important to respect all religions to be “truly Indian.”’ Tolerance is also a religious value: ‘Indians are united in the view that respecting other religions is a very important part of what it means to be a member of their own religious community.’

But for all this mutual respect, segregationist impulses remain strong. For example, 36% of Hindus do not want Muslims as neighbors (though that does mean 64% are willing to accept them). Likewise, opposition to interfaith and intercaste marriages is widespread. About 80% of Indian Muslims disapprove of, and wish to prevent, interfaith marriages. Roughly two-thirds of Hindus feel the same way.

Disappointingly, Indians also prefer making friends within their own religious community. Religious identity has a strong hold: 64% of Hindus say it is very important to be Hindu in order to be ‘truly Indian’. North Indian Hindus say speaking Hindi—a language fiercely resisted in the country’s south and northeast—is essential, too.

Although Indians have many beliefs in common—there are startling overlaps among all faiths on topics such as reincarnation, karma, identification with a caste, and the purifying power of the sacred Ganges River—there’s a marked preference for religious segregation. Adherents of every religion want to maintain a safe distance from those of other faiths.

What are the national political implications of all this, at a time when the ruling party’s Hindutva dogma has put identity politics in the ascendant? Many supporters of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has long propagated a ‘Hindi–Hindu–Hindustan’ version of Indian nationalism, strongly believe that being Hindu and speaking Hindi are vital to being truly Indian.

That suggests a risk of discrimination against India’s minorities. Yet, according to the Pew survey, only one in five Indian Muslims say they have faced religious discrimination. People in the south, where the BJP struggles to win votes, emerge in the study as less religious and more inclusive and accommodative.

At the same time, 95% of India’s Muslims say they are proud to be Indian and 85% agree with the statement that ‘Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others.’ Those Hindutva ideologues casting doubt on the patriotism of India’s Muslims should take note.

Other religious fault lines in Indian politics also appear less troubling than previously imagined. Although Pakistan has sought for three decades to foment disaffection towards India among Sikhs in Punjab, the study finds that 95% of Sikhs say they are very proud to be Indian, while 70% say that a person who disrespects India cannot be a Sikh.

Overall, the study reveals that India is a highly religious country that is profoundly committed to respecting its diversity while practising what Pratap Bhanu Mehta calls a ‘segregationist form of toleration’. Given this, reviving and reaffirming the civic nationalism enshrined in India’s constitution, with its commitment to empowering the individual citizen rather than privileging his or her religious group, is all the more important.

This is the thesis of my most recent book, The battle of belonging (to be published internationally in October as The struggle for India’s soul). The Pew survey confirms some of my concerns, but also offers hope for affirming a liberal constitutionalism that the BJP’s nationalism has sought to eclipse.

There’s one more straw in the wind for those, like me, who would like India’s religious identity politics to yield to a focus on governmental performance and issues that affect citizens of all faiths. The Pew survey shows that unemployment, corruption and crime are the top concerns for people of all religious groups. A government that tackles those effectively, irrespective of whether it does so in Hindi or after offering prayers at a Hindu temple, is bound to win gratitude—and votes.