An object lesson? The first British nuclear ballistic missile submarine program

Posted By James Goldrick on March 18, 2016 @ 12:30

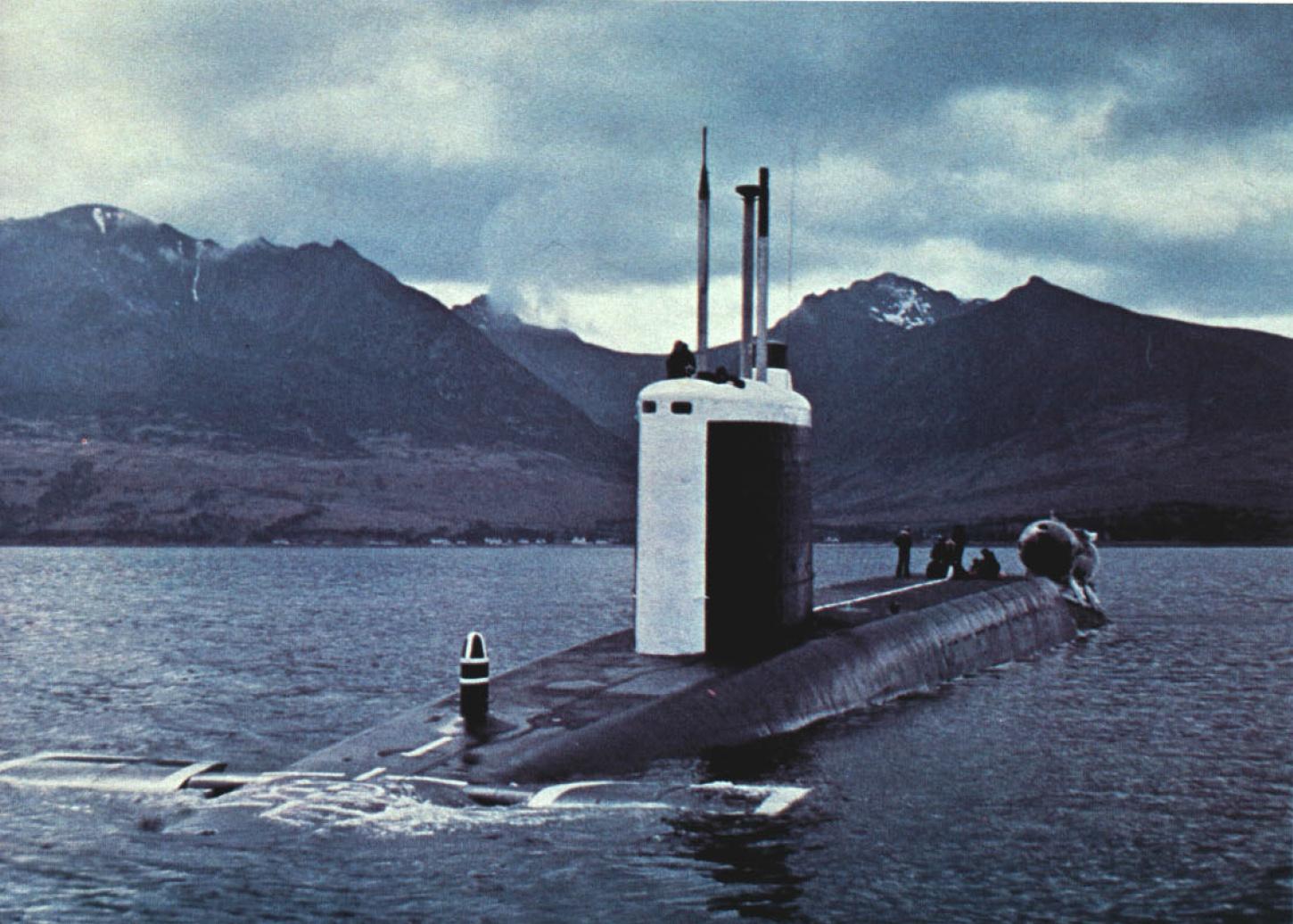

The recently published history of the British submarine service since 1945, The Silent Deep [1] by Peter Hennessy and James Jinks, contains much food for thought for those interested in Australia’s future submarine capability. One particular episode, the construction of four nuclear powered ballistic missile submarines to carry Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent in the form of the Polaris A3 missile, is worth exploring in detail.

The recently published history of the British submarine service since 1945, The Silent Deep [1] by Peter Hennessy and James Jinks, contains much food for thought for those interested in Australia’s future submarine capability. One particular episode, the construction of four nuclear powered ballistic missile submarines to carry Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent in the form of the Polaris A3 missile, is worth exploring in detail.

The order for the quartet was announced in February 1963, in the wake of the US–UK Nassau agreement of December 1962. The rate of progress required was such that the staff requirements for the new class were completed within eight weeks of the Nassau Agreement and the overall design approved less than a year later. The first boat (7,500 tons on the surface and 8,400 tons dived) was laid down in February 1964 and completed its trials in August 1967. The first operational deterrent patrol was conducted in 1968, nearly in accordance with the original schedule, while the last boat commissioned in December 1969. The project remains a remarkable achievement, one much smaller than, but nevertheless directly comparable to, the American effort that saw 41 SSBNs completed between 1961 and 1967.

Several points are notable. First, there was strong and continuing oversight by a well-led project team, designated the Polaris Executive, which had the authority to make decisions and force change. The chief executive officer assigned at the start of 1963 remained in office until the first boat was fully operational. One of his earliest initiatives was to circulate within the departments of state (aimed most particularly, at the Treasury) a paper entitled ‘What’s So Special About the Polaris Programme?’ which made clear the formidable challenges ahead.

Second, there was no competition. Only one builder, Vickers-Armstrongs at Barrow in Furness, was already building nuclear submarines and had some—although not all—of the expertise required to embark on a ballistic missile submarine construction program. Cammell Laird, the second builder, was only brought on line when it became apparent that Vickers couldn’t manage all four boats in tandem with the existing attack submarine construction line. Vickers remained the lead yard. In fact, most of the biggest problems with the whole program derived from the fact that Cammell Laird experienced a steep learning curve in developing the necessary techniques for nuclear submarine construction from scratch.

What substituted for competition was a sustained effort to identify and contain cost, to improve—and this was vital—quality control to achieve a standard of hull and machinery construction that had never been reached before. Vickers understood the requirement, but still had to vastly expand its expert workforce if both SSBN and SSN production lines were to be maintained. Such quality control included extensive training programs to give design staff and technicians the skills they needed to move from relatively simple, shallow diving diesel-electric craft to the much more demanding requirements of the missile boats. This included working with new varieties of high tensile steel and developing the welding techniques to match. It also included much more attention to detailed design and the inter-relationship of major systems and sub-systems than had ever before been required or attempted. In retrospect, this remained one of the weak areas of the program—and it’s still one of the key challenges for the successful new build of any submarine. The associated changes in Vickers’ manpower indicate the scale of the effort (and may cast some light on the Australian requirement for building the future submarine). The yard force increased from 3,100 men in 1963 to 4500 in 1967, but the support staff—including planning, testing and quality control—went from 800 to 2,400 in the same period.

Next, problems were identified and a solution sought as early as possible; there was little or no ‘learned helplessness’ and if money had to be found, it was, since the requirement for contingency funding to be available was understood from the start. Most impressive was the early acceptance that a British decision to eschew stainless steel piping in the first indigenous naval nuclear reactor was gravely flawed. The British couldn’t fix the problem from within their own resources and keep to the schedule. Notwithstanding the loss of British ‘face’ and the foreign currency cost, American assistance was asked for and given.

There’s one ironic footnote to the British SBBN programme, not mentioned in The Silent Deep but since acknowledged by other UK authorities. Training and preparing eight nuclear and missile qualified crews for the four twin-crewed boats in such a short time placed a severe strain on the manpower of the British submarine service, already under stress introducing the nuclear powered attack boats. Britain was only able to maintain its declared number of operational submarines for NATO over the critical period 1965–68 because Australian and Canadian submariners, in training and gaining experience for their brand new, British-built, diesel-electric submarines aboard RN units, made up some of the manning shortfall. Australia’s Collins class program applied some, but not all the lessons that the British had learned from their SSBN build. It will be vital that the new Future Submarine Program will have learnt and applied them all.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /an-object-lesson-the-first-british-nuclear-ballistic-missile-submarine-programme/

URLs in this post:

[1] The Silent Deep: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/183977/the-silent-deep/

Click here to print.