The United States Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel recently released his Department’s new Arctic Strategy during a speech at the Halifax International Security Forum. This document follows the US National Strategy for the Arctic Region released by President Obama in May. Given the recent posts on Australia’s Antarctic strategy, this is a useful benchmarking opportunity for our own policy. More generally, as a new regional policy the two American statements offer some insight into influences on wider US defence strategy.

The United States Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel recently released his Department’s new Arctic Strategy during a speech at the Halifax International Security Forum. This document follows the US National Strategy for the Arctic Region released by President Obama in May. Given the recent posts on Australia’s Antarctic strategy, this is a useful benchmarking opportunity for our own policy. More generally, as a new regional policy the two American statements offer some insight into influences on wider US defence strategy.

At face value, the US DoD’s strategy shares a number of features with the Australian policy outlined by Peter Jennings and Anthony Bergin, and implied in the recently commissioned 20 Year Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan. Most obvious is a recognition that things in the polar regions are changing; international interest and human activity in both areas are increasing as they become more accessible and there’s a real focus on their economic potential. But America’s recognition is caged in uncertainty; things are changing in the Arctic, but no-one knows yet just what they’re changing to, or what this means. There is a strong flavour of ‘wait and see’ to the US DoD’s approach—in that regard, it’s more reminiscent of Australia’s 2009 Defence White Paper than the 2013 one.

To address this uncertainty, the US strategy shares Australia’s emphasis on science. In the American case, this has a fairly simple purpose: forecasting just what environmental changes afoot in the region will mean; and what resources it may hold. The aim is to inform national and international decision-making rather than, as Anthony suggests of Australia, to garner influence in international fora. The US is more emphatic that climate change is a factor that must be understood.

The two policies also seem to agree that the respective defence organisations have only a supporting role in overall national efforts in the polar regions: the US seems to have little appetite for expensive, dedicated Arctic military capabilities at this stage and it expresses a gratifying caution about stimulating an arms race. Finally, both emphasise the need for collaborative international management of these regions and for good stewardship of territories claimed by nations, although (with one exception) the US approach is less dependent on formal treaty arrangements for that purpose.

Where the policies seem to differ strikingly is in the securitisation of the Arctic: the US national strategy’s first Line of Effort is ‘Advance US National Security Interests’ and this is supported by subordinate principles in the Defense strategy (e.g., homeland defence, improved domain awareness, freedom of navigation). That’s hardly surprising, considering that part of the US homeland (Alaska) lies within the Arctic, that the polar route is a key strategic approach to North America, and that the receding ice cap is opening navigation channels near or through national territory: characteristics that don’t apply to Antarctica. While it’s reluctant to commit to specialised Arctic defence capabilities, the US strategy does allow for judicious strategic investment in security infrastructure, unlike Australia in the Antarctic.

The US strategy is also striking in that it highlights energy security as a national interest in the Arctic, implying a potential willingness on the part of Washington to exploit its energy resources. This differs from the traditional reverence for the pristine Antarctic and seems to vindicate Patrick Quilty’s assessment that, ultimately, economics and not environmental values will determine what Antarctic mineral resources are exploited.

The Arctic policy may hint at things to come in US strategy in its frank acknowledgement of DoD fiscal constraint and its impact on capability development. It implies that specialised Arctic capabilities may struggle to compete for investment. The consequent need to achieve security by other means leads to a bold (for the US) recommendation: that it should accede to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in order to simplify the task of securing US interests in the Arctic. DoD has argued this for other parts of the world for similar reasons, immediately running into conservative orthodoxies in Congress that abhor such international agreements, seeing them as threats to US sovereignty. Internationalism may be a more consistent feature of Democratic security policy going forward, but it remains to be seen how much is achieved ultimately.

The American Arctic strategy, like Australia’s Antarctic one, is a measured response to a strategic problem of uncertain dimensions. Both countries know the respective regions are important, and becoming more so, but neither seems convinced of the need for bold change at this point (although Australia’s Strategic Plan may surprise us, when it’s revealed). The inherent uncertainty of the polar regions will likely diminish over the next few years, especially in the Arctic, as the region becomes better travelled and understood. Where uncertainty becomes opportunity, especially for resources and despite well-intentioned strategies, we can expect to see competition in these newly salient parts of the global commons.

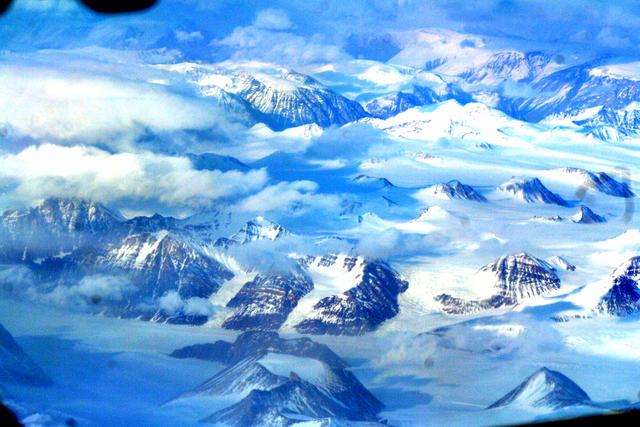

Andrew Smith is an independent researcher who has worked in the United States. Image courtesy of U.S. Air Force.