‘I’m also very confident in terms of the methodologies that have been developed and refined over the course of many of these projects and I’m very confident in the fidelity of the data that we have.’

— Minister for Defence Linda Reynolds, Supplementary budget estimates hearings, 29 November 2019

The October and November 2019 Senate estimates hearings for the Department of Defence followed a familiar pattern: extended discussion about the number of Australian jobs associated with projects for building and sustaining naval vessels and an outcome that did little to clarify many, or even most, of the numbers involved.

To begin with, there was considerable confusion at the hearings about the meaning of key indicators of employment. ‘Direct jobs’ cover the people employed by prime contractors and their subcontractors, working in dockyards or associated facilities. ‘Indirect jobs’, sometimes described as ‘flow-on jobs’, consist of jobs supporting the provision of all other Australian inputs along project supply chains.

But projects also generate jobs in other areas of the economy. One category that wasn’t mentioned at the hearings is ‘consumption-induced jobs’, which are jobs created in businesses that sell consumer goods and services to people working on projects. The skills associated with those jobs can differ markedly from the skills required for naval shipbuilding and sustainment.

Another category is jobs that come from spillovers. A ‘spillover’ is a new technology or skill created by a project that other areas of the economy use to generate employment of their own. Because that employment is extraordinarily difficult to quantify, it’s not covered in Defence’s job figures. At the hearings, that point wasn’t made as clearly as it might have been.

Not surprisingly, direct jobs are often estimated by prime contractors. But neither a prime nor Defence normally has insight into the far reaches of supply chains and beyond, especially during the early phases of projects. Consequently, indirect jobs tend to be estimated initially using economic models and refined later as more project-specific data becomes available. Consumption-induced jobs are estimated solely through economic modelling.

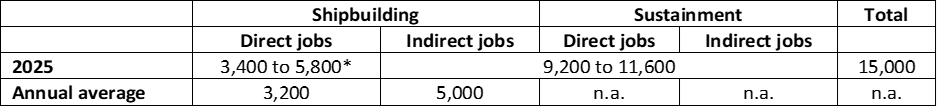

Senators at the hearings were interested primarily in two sets of job numbers covering direct and indirect employment for shipbuilding and sustainment—one for 2025 and the other for all years of Defence’s naval shipbuilding plan expressed as an annual average (see table 1). For both sets, the data provided by Defence falls short of what’s required for adequate coverage and categorisation.

Table 1: Shipbuilding and sustainment jobs by key category

n.a. = not available.

* The precise figures for direct shipbuilding jobs in 2025 are difficult to determine, partly due to confusion about whether the correct year is 2025 or 2026. At the October hearing, a figure of 5,200 was initially provided for 2025 (page 15 of transcript) but later increased to 5,800 (page 16). The latter figure was made up of 5,200 for the future frigates and future submarines and 600 for the Pacific patrol boats and offshore patrol vessels. However, further testimony from Defence (pages 73–74) indicated that in 2025 the future frigate program (1,452) and future submarine program (1,341) would together support 2,793 direct jobs rather than 5,200—suggesting that either the 5,200 figure was incorrect or Defence had defined direct shipbuilding jobs to include additional project-related activity like facilities construction or sustainment.

There are three additional limitations to consider. First, Defence’s figures include a substantial number of jobs carried over from previous projects. That obscures the all-important issue of how aggregate employment numbers will change. Carryover is especially significant for sustainment—a problem that also applies to recent official announcements on job creation for military vehicle assembly.

Second, the annual averages for shipbuilding are based on the implicit and untested assumption that companies constructing the Pacific patrol boats and the offshore patrol vessels will secure equivalent follow-on work in the medium to long term.

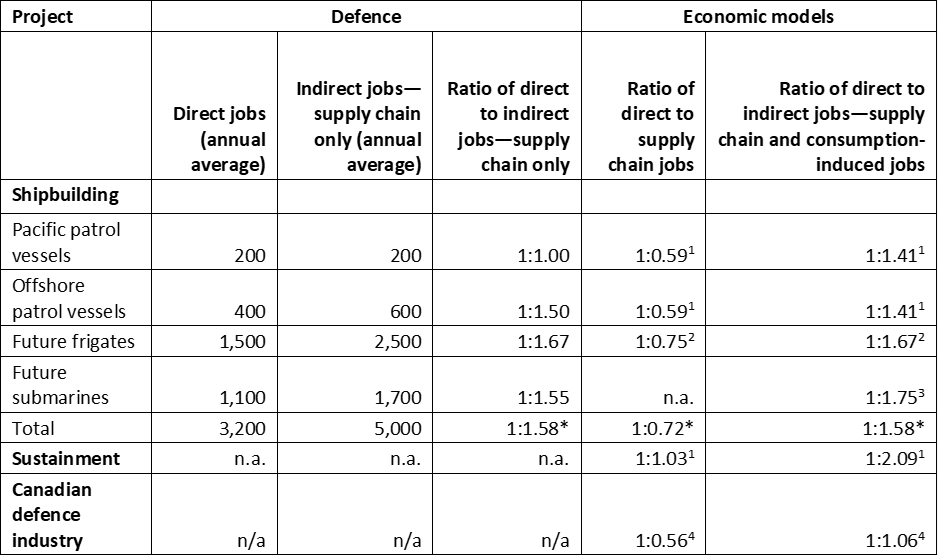

Third, Defence said at the October hearing that its estimates of indirect jobs contain supply chain jobs only. Relevant economic modelling suggests those figures also incorporate a substantial consumption-induced employment effect, at least for larger build projects (see table 2). Consumption-induced jobs add to employment across the economy—but not in naval shipbuilding and sustainment.

Table 2: Ratio of direct to indirect jobs in naval shipbuilding and sustainment

n.a. = not available; n/a = not applicable.

* Weighted average.

Sources:

1. ACIL Tasman, Naval shipbuilding and through life support, report to Australian Industry Group, 2013, 17.

2. BIS Oxford Economics, The economic contribution of BAE Systems in Australia, 2018, 24.

3. Department of Defence, Building submarines in Australia—aspects of economic impact, 2015, 5.

4. Figures based on contribution to Canada’s GDP for all Canadian defence industry, not just shipbuilding. Binyam Soloman and Christopher E. Penny, ‘Canada’s defence industrial base’ in Keith Hartley and Jean Belin (eds), The economics of the global defence industry, Routledge, 2020, 445. Data also available here.

If those three limitations hold, I estimate additional or ‘new’ jobs will account for around one-third of the total number of jobs that naval shipbuilding and sustainment are expected to support in the period ahead. That support covers an estimated 15,000 jobs, measured on an annual average basis. The remaining two-thirds consists of numbers for jobs carried over from previous Defence projects, in serious doubt or created in non-defence areas of the economy. All those figures are maxima since they exclude the impact on national employment of the economic costs associated with paying for and resourcing projects.

There was also some confusion at the October hearing about a total job figure for the future frigate build of 6,300 attributed to former minister Christopher Pyne. That figure is substantially higher than Defence’s current figure of 4,000. The department claims that the difference between the two figures is attributable to the Pyne figure including consumption-induced employment.

An alternative, and perhaps more likely, explanation is that the 6,300 jobs relate to 2028—the project’s first year at peak production—and that Defence’s figure of 4,000 is an annual average ‘smoothed’ across peak and non-peak levels of project activity. The problem of Defence juxtaposing annual average data and peak annual data extends to the department’s testimony in October that direct jobs for the future frigates of 1,500 (an annual average figure) will approach 2,500 (a peak annual figure) by 2028.

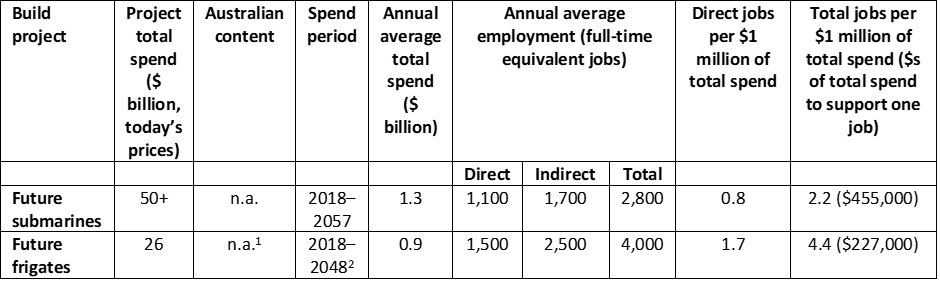

Finally, taken at face value, Defence’s estimates paint a picture of job creation that’s counterintuitive: the future frigate build generating many more jobs than the much larger future submarine build (see table 3).

Unfortunately, that’s difficult to assess without additional data including an indication of each project’s Australian content. The assumed levels of domestic content underpinning Defence’s job estimates for most build projects weren’t presented at the hearings and haven’t been disclosed elsewhere.

Table 3: Comparison of job creation for future frigates and future submarines

n.a. = not available.

1. Estimates vary of the Australian content associated with this project, from a 50% minimum, to 58% contracted, to 65–70% predicted by the contractor (see Senate estimates, 5 April 2019, answer to question on notice 43).

2. The spend period of 2018–2048 was used by BIS Oxford Economics, The economic contribution of BAE Systems in Australia, 2018, 22, to estimate employment for the future frigates.