In a week where we’ve looked back at ASPI’s first 15 years it may be useful to contemplate what the next 15 years might look like for the Institute. Will ASPI survive to 2031? Will there be a need or, more fundamentally, a demand for its work? How different might ASPI be in 15 years, and what will the wider policy and think tank environment be like?

The honest answer, of course, is: who knows?! We’re talking about a future at least five federal elections away—an eternity to some Canberra institutions—at a time when the pace of change in Australian public and strategic life is dramatically increasing. But it’s not as though policy challenges will go away. That gives rise to the hope that Governments, Parliaments, officials, journalists and business people will still want contestable policy advice. No thinking think-tanker would want to pin their institution’s future on just such a hope. In a decade and a half perhaps policy contestability will emerge from artificial intelligences grown in strangely glowing gloopy miasma—think vats.

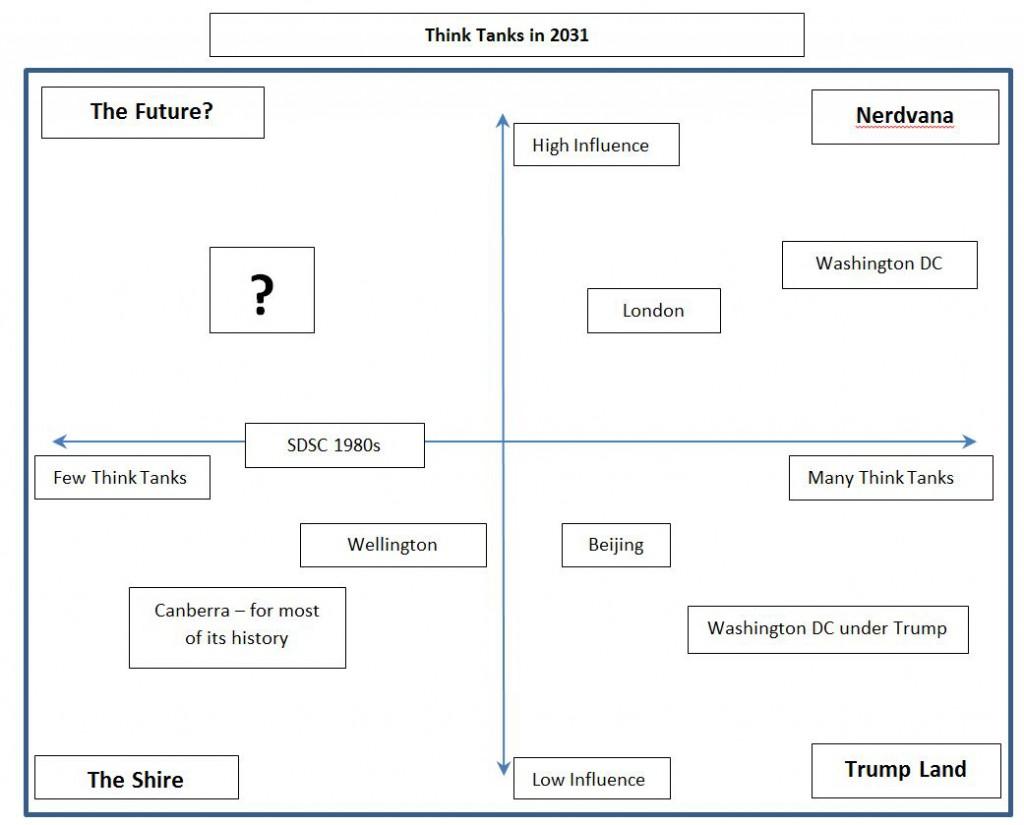

But I digress. Let’s turn instead to something as lasting as the stars, which is the robust intellectual framework known in business schools as the two-by-two. Here I contend that four broad future possibilities exist for Australian policy think tanks. These futures reflect the interaction of the two most fundamental drivers in the lives of such institutions: the degree to which there is a demand for their product—that is to say the influence they have on the policy world, and second, the competition that exists in the think tank field—how may institutes are out there, slugging away for influence? The combination of these factors is shown below.

An environment where there are multiple think tanks exerting a high level of influence on public policy—let’s call this place ‘Nerdvana’—does actually exist in Washington DC and to a lesser extent in London. With a Metro ticket and a pair of loafers one need never lunch alone in Washington DC. The city’s think tanks are full of serious people with serious ideas and a high expectation they’ll be listened to by officials, many of whom were and will be again, think tankers.

America’s political environment and sheer size encourages Nerdvana. Think tanks act as holding pens for talented people who support the major party not presently running the White House. American universities produce a stream of high quality graduates whose very definition of heaven is to cuddle up with the latest General Accounting Office report. They work for a pittance producing high quality analysis. The US system isn’t afraid of ideas and thrives on contest. Finally, deep pocketed Americans bequest think tanks with large endowments. For the right amount of money you too can have a chair named after you in lecture theatres all around K Street. For all those reasons Nerdvana by the Molonglo is unlikely. The political environment is simply too different.

Could there ever be a world where we see large numbers of think tanks operating in an environment where they have relatively low influence? This might be thought unlikely because low influence think tanks generally won’t attract money (and therefore survive) for long. However Washington DC might offer an example of this if Donald Trump wins the Presidency. Welcome to Trump Land. Large numbers of Republican-supporting strategists have already said they won’t serve in a Trump administration. DC’s think tanks could become homes for two establishment parties out of office. They’d aim to outlive Trump hoping he’d be a one term wonder. Beijing’s many think tanks also strike me as living in a low influence Trump Land. Whatever they’re there to do, it’s most certainly not about creating contestability in public policy. That said, Beijing’s thing tanks do quietly try to shape official policy, which they can do by being more open to foreign contacts and thinking. It’s a narrower crawl space than in Western capitals.

The left hand side of the diagram is where Canberra’s think tanks operate. Obviously they are fewer and smaller than their US counterparts. For most of Canberra’s history the town has operated as The Shire—a quiet place where the smallness of think tanks was matched only by their ineffectiveness. Today, people wouldn’t believe the privations of mid-1980s Canberra which greeted me as a Masters student at the ANU. Back then coffee was instant, Civic closed (all of it) at noon on Saturday and Iced VoVos were 5 cents each in the HC Coombs Building tea room. There was the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre and it’s true to say it had a substantial impact on defence policy thinking in the lead up to the 1987 Defence White Paper. But that was it. The rest was heat haze and closed shops, mentally and physically.

Finally we come to The Future, the quadrant where we find some relatively influential think tanks, which is where a positive assessment of Australia’s think tank landscape might take us by 2031. Now, compared to the 1980s, there are already a number of established institutions, not only in Canberra but also Sydney and Perth, where strategic policy is seriously discussed. The media, Parliament, business community and many Government officials accept think tanks as a legitimate part of the policy landscape. There’s also a more widespread community expectation of being engaged on the content of policy. As senior politicians keep telling us, the public service struggles to meet those expectations and that’s where adroit think tanks can cultivate influence. It’s hard to see these factors reversing as we move towards ASPI’s 30th in 2031.

That said, no one owes any of us a living. All think tanks are only as good as their last report and it’s the contest of ideas that encourages new thinking. The price of relevance is to reach for excellence. That’s what makes a place like ASPI worth supporting for, I very much hope, another 15 years.