For your (virtual) bookshelf: Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, Richards J. Heuer, Centre for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1999.

In the 1990s, the CIA commissioned a study on the nature of intelligence analysis to try to understand why they had an unenviable track record of missing (more accurately, underestimating) some major developments in areas they had been watching closely, such as the decline of the Soviet Union. Or, as Jack Davis, himself a former CIA analyst memorably put it, the CIA analysts had mind sets that helped ‘get the production out on time and keep things going effectively between those watershed events that become chapter headings in the history books’.

Heuer’s monograph, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, is something of a classic in the field, and it sheds much light on the frailties of the human mind regarding the difficulties of making objective assessments of complex situations when only incomplete information is available. This is a very readable book in that it is not a theory-based approach, and it is full of examples of how we can fool ourselves into being surer than we have any right to be.

Here’s one of my favourites, which illustrates a subtle point about decision making. It’s almost axiomatic after any intelligence ‘failure’ (which may or may not actually be a failure in the true sense of the word) that more collection is one of the remedies—if only the analysts had had more information, the implied reasoning goes, then they would have had a better chance of getting it right.

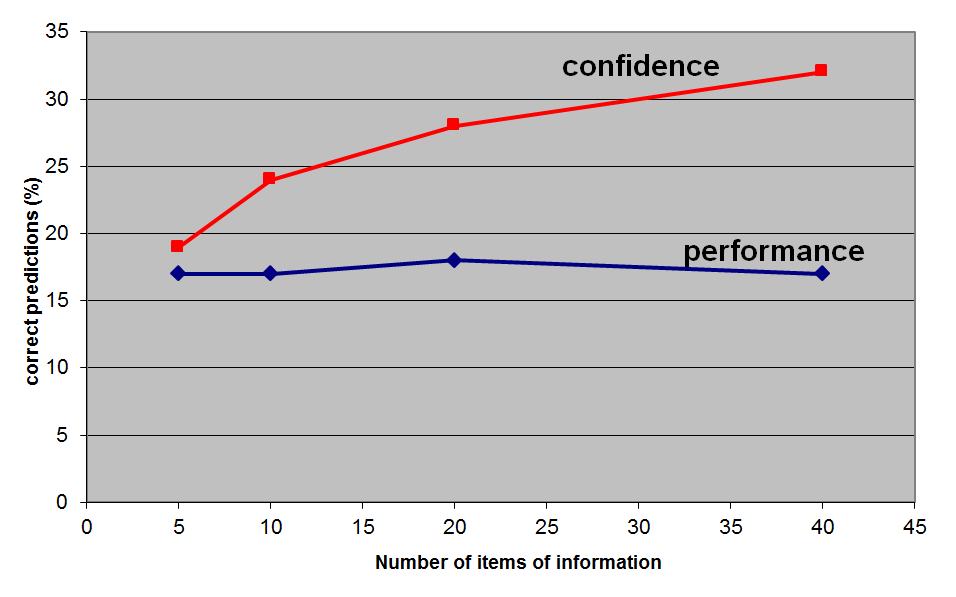

Not necessarily so, says Heuer, and he has experimental evidence to back him. In the experiment, experienced horse handicappers were presented with datasets of variable sizes for a set of horse races (with the race and horse identities concealed). They were asked to predict the outcomes based on variables such as the weight to be carried, the percentage of races in which the horse finished first, second or third during the previous year, the jockey’s record and the number of days since the horse’s last race. Their performance at the task is shown in the graph below. With a small number of variables, their predictions were accurate between 15% and 20% of the time. Importantly, their assessment of their accuracy almost matched their performance. However, as more data was provided, their confidence in their predictions grew steadily—in contrast to their performance, which was resolutely unaffected by the extra data.

Graph. Decision making: perception vs reality

Heuer concludes the discussion with an observation that this effect isn’t limited to the world of intelligence. I’ve argued in the past that the increasingly elaborate process surrounding the development of the Defence capability plan (52 major pieces of documentation at last count) runs the risk of prioritising information over analysis.

Heuer has another example, and an observation (emphasis added):

A series of experiments to examine the mental processes of medical doctors diagnosing illness found little relationship between thoroughness of data collection and accuracy of diagnosis. Medical students whose self-described research strategy stressed thorough collection of information (as opposed to formation and testing of hypotheses) were significantly below average in the accuracy of their diagnoses. It seems that the explicit formulation of hypotheses directs a more efficient and effective search for information.

In short, Heuer makes a very convincing case for the scientific method as the right basis for intelligence analysis and, by extension, other areas of complex decision making.

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist.