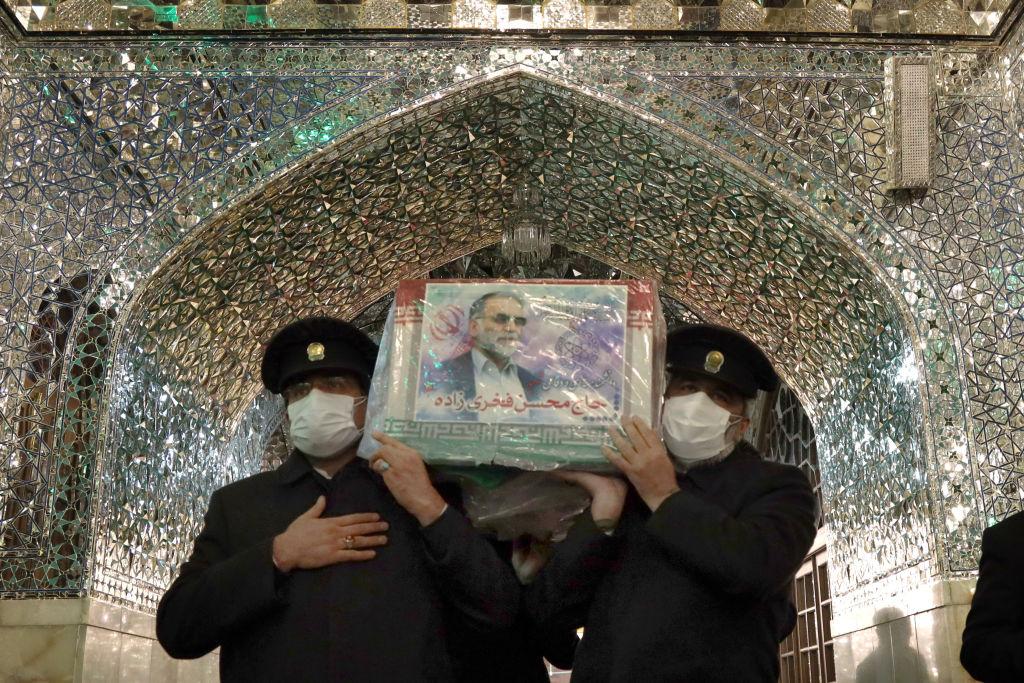

Media speculation has gone into overdrive since the assassination of Iran’s top nuclear scientist on Friday. Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was an important albeit little-known figure in the Iranian government and was the head of research and innovation in Iran’s defence ministry.

Fakhrizadeh was also an integral figure in Iran’s pre-2004 nuclear weapons work, and his role in Iran’s Amad program in the early 2000s had long made him a person of interest to those seeking to unravel Iran’s historical weapons program. Fakhrizadeh’s role in Iran’s defence establishment also raised questions about the nature of his ongoing research, including whether there were any elements that related to nuclear weapons.

There are suggestions he may also have held the positions of deputy defence minister and brigadier general with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Those appointments would have accorded him a level of seniority broadly equivalent to that of IRGC major general Qassem Soleimani, who was assassinated by US forces in Baghdad in January.

Israel has, unsurprisingly, emerged as the most likely culprit behind Fakhrizadeh’s killing. As noted by Trita Parsi in Responsible Statecraft, Tel Aviv had the expertise, capacity and motive to conduct the attack, and it has carried out similar assassinations before. Israel has been identified as being likely behind the murder of four other Iranian scientists between 2010 and 2012, and the attempted murder of several others. It’s also likely that the US was complicit in the attack, at a minimum providing Tel Aviv with a green light to conduct the attack.

Importantly, there are some differences between the level of sophistication of the attack on Fakhrizadeh and the earlier attacks on other Iranian scientists which sets Fakhrizadeh’s murder apart from the earlier events.

The earlier attacks appear to have involved one or two assailants, who either attached remote-controlled bombs to the vehicles of their victims or shot their targets at close range. The attack on Fakhrizadeh, on the other hand, appears to have been very well orchestrated, involving multiple attackers and possibly a pre-positioned vehicle-borne bomb. This raises questions about whether Israel—assuming it was behind the attack—had intelligence or tactical support from either the US or Iranian dissident groups such as Mujahedin Organisation of Iran (MEK), which Israel is suspected of having worked with in the past.

Intriguingly, Iran’s condemnation of the attack included a reference to ‘the mercenaries of the oppressive Zionist regime’ as being behind it. This suggests that Israel may have used proxy forces like MEK or possibly the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Al-Ahwaz to carry out the attack on its behalf.

The assassination of Fakhrizadeh was clearly symbolic. It was the first known assassination of a figure associated with Iran’s nuclear program in over eight years. It also occurred at a time when political transition in the US has raised hopes of a renewal of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Iran’s nuclear program, given President-elect Joe Biden has committed to resurrecting the deal.

It is also likely to be more than coincidental that US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reportedly met with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Saudi Arabia on 22 November, possibly to advance elements of an anti-Iranian coalition in the dying stages of the Trump presidency.

In the absence of any publicly available evidence indicating that Iran has undertaken any substantive research related to nuclear weaponisation since 2003, it appears Fakhrizadeh was targeted because of his historical role, not because of any contemporary work that he was undertaking.

International Institute for Strategic Studies associate fellow Mark Fitzpatrick argues that Fakhrizadeh’s assassination was a political act that will not degrade or impede Iran’s nuclear program. Ellie Geranmayeh from the European Council on Foreign Relations supports this view, noting, ‘While Fakhrizadeh is believed to have played [a] crucial role [in] advancing Iran’s nuclear activities, the program is not beholden to one person …The objective behind the killing wasn’t to hinder the nuclear program but to undermine diplomacy.’

But it appears likely that the perpetrators of Fakhrizadeh’s assassination intended to do more than just spoil any chance for a renewal of cooperation with Iran on its nuclear program and the reinstatement of US participation in the JCPOA. It’s likely that they are also seeking to provoke a response from Tehran that would legitimise further punitive action against Iran by Israel or the US. The implications of this could prove catastrophic.

Former CIA director John Brennan commented that Fakhrizadeh’s assassination was ‘a criminal act and highly reckless’, and risked ‘lethal retaliation and a new round of regional conflict’. Brennan also noted, ‘Such an act of state-sponsored terrorism would be a flagrant violation of international law and encourage more governments to carry out lethal attacks against foreign officials.’

Fortunately, despite the killing of Fakhrizadeh being arguably a de facto declaration of war, Tehran appears set to continue the policy of strategic patience that it adhered to after the assassination of Soleimani. It also followed this approach after the apparent attack on the Natanz nuclear facility and possibly other industrial sites in the middle of the year.

While Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei called for the ‘punishing’ of the perpetrators of the attack ‘and those who commanded it’, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani noted that Iran was ‘too wise to fall into Israel’s trap’ and that it would respond and punish the perpetrators ‘in due time’.

What Iran will also be doing is reviewing its overall security posture, potentially including any latent nuclear weapons ambitions. The great irony of this situation is that there still doesn’t appear to be any compelling evidence that Iran has actually taken a decision to pursue a nuclear weapons capability or that it has advanced the weapons research it ostensibly concluded in 2003.

The assassination of Fakhrizadeh may not only fail to achieve its core objectives, but may also prove disastrously counterproductive by providing the catalyst to convince policymakers in Tehran that they need the strategic deterrent capability that only a nuclear weapon can provide.