The news that Australia has done a deal to exchange intelligence with Iran generated some fierce criticism from independent MP Andrew Wilkie, who described the arrangement as ‘complete and utter madness from a security point of view’. From an alliance perspective, at first glance he seems to have a point.

A week previously, the United States announced that it was ramping up its intelligence sharing with Saudi Arabia to increase the effectiveness of Saudi air operations against Iranian-backed anti-government forces in Yemen. America’s interests are engaged because the Yemeni government has been an important ally in American efforts to curtail the local al Qaeda franchise.

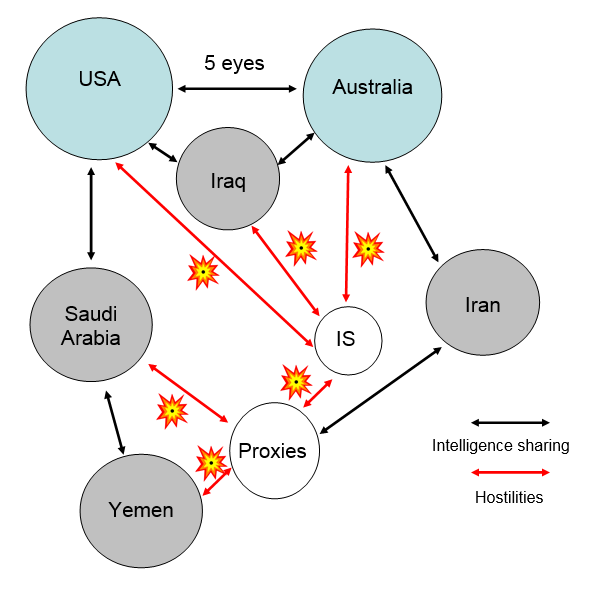

So we have the situation where Australia and the US, rock-solid allies and intelligence partners through the Five Eyes partnership, have struck intelligence sharing deals with opposite sides in the Yemen conflict. And it’s actually more complicated than that. Iran is also helping out in operations against IS in Iraq, to which both Australia and the US are contributing. As near as I can make out, the situation looks something like the schematic below. (And if this looks complicated, it’s much simpler than the graphic representation of wider security interests in the Middle East.)

To a strategist, that diagram seems to bear out Wilkie’s criticism. The overall security strategy seems fragmented and at times contradictory. For example, assuming that Australia wants the same outcomes as the US, we find ourselves hoping that Iran is successful in its efforts in Iraq but unsuccessful in Yemen. (And Iranian proxies elsewhere, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon with their anti-Israel activities, only further cloud the picture.) Given the tightness of the ANZUS allies, it’d be expected that Australia would thoroughly discuss the deal with the US before going public—though comments from the State Department suggest otherwise.

From a security angle, intelligence is one of the tools of state power and it makes little sense to share that power with a state that doesn’t align with our preferred model of the world. But that’s not the only way to think about the problem. To an economist, the diagram above would look familiar, as it has many of the characteristics of a trade network. That’s the key to seeing what’s going on here. Intelligence products have value as a trade good, and they can be exchanged for other goods. We’re offering up a limited amount of intelligence cooperation in return for a quid pro quo—in this case, Iranian cooperation with Australia on efforts to defeat IS and help counter the organisation’s extremist message.

Australia won’t be opening up its five-eyes intelligence apparatus for Iran to exploit for its own national strategy—in fact, we’ll probably hand over as little material as we can to secure the benefits we want. The trick will be quarantining Iran’s access to intelligence to subjects where the two nations’ interests converge. That’ll require some careful handling, and we’ll need to keep material handed over to a narrow focus on those issues. The opposition leader Bill Shorten neatly summed up the tension:

‘… because we have a current convergence of interests does not mean that Australia should lower its guard or be any less vigilant to some of the issues… We will be pragmatic and we won’t be naive that if there is a beneficial relationship in one part of our relationship with Iran, that doesn’t automatically mean that everything else has changed.’

In sharing intelligence with a country we’d normally disagree with, we’re certainly not setting any precedents. Last year the US decided to share intelligence on IS with Russia, and that’s despite Russia’s continued destabilisation of eastern Ukraine and other unhelpful security positions. It’s worth recalling the post-9/11 environment as well. After the US homeland attacks, the US and Russia agreed to cooperate on intelligence efforts against al Qaeda, which produced disquiet on both sides of the relationship. The KGB didn’t like it, and I well recall NSA Cold War veterans being deeply troubled by the idea of American intelligence being marked ‘releasable RUSSIA’. But security challenges are remarkably malleable and sometimes realpolitik prevails.

In fairness, Wilkie doesn’t focus purely on security in his criticism. He makes two other assertions. First, that Iranian intelligence has been of poor quality and sometimes ‘downright misleading’ and therefore of little value as a trade good. If that turns out to be the case, Australia will have to decide whether the exchange is worth continuing, which will depend on the net benefits of the deal as we assess them.

Secondly, and to my mind more importantly, he asserts that Iranian intelligence is sometimes based on torture, which should be unacceptable to Australia. It’s hard to argue with that, though I’d note that we don’t seem to apply that rule to other intelligence partners—including the United States.

On balance, there’s nothing too surprising about our overture for a closer intel relationship with Iran. It simply reflects the realpolitik of international affairs and it’s not like we’re offering up the family jewels.