As Australia’s foreign and defence ministers and the US secretaries of state and defence prepare to meet for the annual AUSMIN consultations, ASPI has released a collection of essays exploring the policy context and recommending Australian priorities for the talks. This is the last of three edited extracts from the volume’s technology chapter, which proposes five key science and technology areas for greater US–Australia collaboration that carry significant national security and defence risks for both countries.

Removing adversaries’ safe havens: cyber capacity-building with vulnerable nations

While it’s often said that the best defence is a good offence, when you’re outgunned, having friends is better. Neighbours and potential allies who lack cybersecurity awareness and skills and manage their infrastructure accordingly, however, are vulnerable to manipulation and control by aggressive foreign adversaries. This can take the form of cyberattacks, in which sensitive data is exfiltrated or manipulated on their networks, leaving them open to covert influence or blackmail.

In some cases, such activities can be overt, like China’s commercial diplomacy, offering technology and infrastructure to nations unaware of the support commitments, the degree of dependency they incur or the extent to which their systems will remain accessible by a foreign power. Regardless, it’s difficult to trust and collaborate with even friendly nations who leak sensitive information, provide access vectors to adversaries or allow their infrastructure to be co-opted for attacks against others.

Before Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine, the technology sector worked closely with the Ukrainian government to patch and upgrade vulnerable systems. That preparatory work significantly reduced the efficacy of Russian cyberattacks and removed enough of the low-level attack vectors so that, when the war began and they were under pressure, Ukraine and its tech partners were able to focus on responding to the much smaller number of sophisticated attacks Russia had prepared in secret.

That strategy doesn’t scale to other nations during peacetime, since those services ordinarily come with a high price tag that nations mightn’t be prepared to pay. Also, going in and making changes ourselves can come across as arrogant or interfering, fomenting distrust from the nation and its allies, and also ensuring that we inherit the ongoing support burden on top of our own work. A far better strategy is to respectfully help them help themselves—jointly develop initiatives that increase their own capacity to secure and manage their infrastructure, and respond effectively to cyber incidents.

The idea of helping a foreign nation fix the kinds of vulnerabilities that we might have exploited for intelligence collection would once have been unthinkable to the intelligence community. However, now that there’s a degree of homogenisation in our respective technology stacks, the cost of finding a vulnerability that might also affect one’s own systems quickly becomes too high to risk keeping it secret. Defending one’s own networks is far more work than attacking someone else’s, so today cyber defence will almost always be prioritised over intelligence gain.

Ultimately, we all benefit from raising up our neighbours. We’re able to build trust between different nations diplomatically; we can build trade and information-exchange opportunities safely; we can share the cyber-incident response burden across a greater pool of cyber professionals; and, critically, we can focus our limited resources on high-impact cases by disrupting the cyberattack chain earlier in its life cycle, preventing adversaries from even reaching our networks.

Recommendation: AUSMIN should invest in capacity-building programs, including training and professionalisation of the cyber discipline, to improve other nations’ cyber resilience. This includes being prepared, on occasion, to sacrifice technical access to intelligence for the greater good.

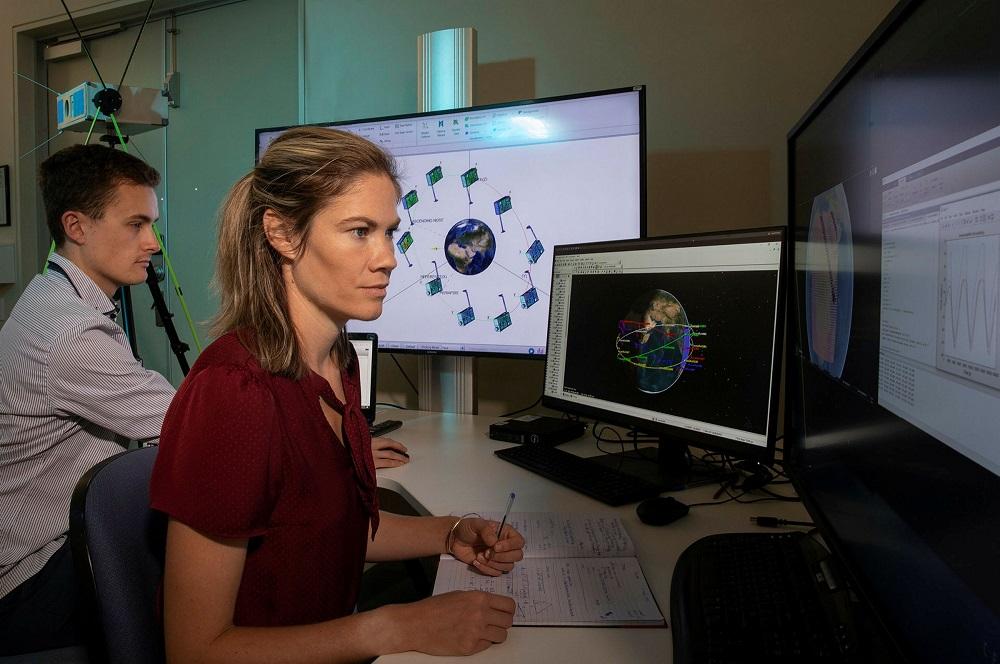

Seeing the bigger picture: data management for analytics, automation and AI

In recent years, artificial intelligence has been listed as a key priority for every major collaborative partnership Australia has signed up to, including AUKUS, the Quad, ASEAN and the Five Eyes. This is due to its enormous potential for being able to identify patterns, solve problems, provide insights and take actions at a speed and scale unmatched by people. However, underpinning all of its potential is the data that it’s based upon. An AI’s success or failure is inextricably linked to how it’s able to learn from data, to interpret it correctly, to make sound inferences and to then apply those inferences in ways that usefully apply in other contexts.

For example, for a good decision to be made, data should be accurate, timely, representative, relevant, trustworthy and appropriately sourced for the problem that the AI’s trying to solve. It should be structured or at least in understood formats, ideally adhering to standards, so it can be compared with or enriched with other data. It should also be assessed for biases so that either they can be mitigated or the AI users can be made aware of the boundaries and context of the answers that the AI will produce.

AI aside, a wealth of data is being generated every second from sensors on military platforms, but to gain the maximum impact from data to support military decision-making, it’s best enriched with contextualising information such as, say, environmental data, secret intelligence, commercial records, cyber data and so on. However, even efforts to collect together similar sensor data from across the army, navy and air force in the same region are extremely difficult, let alone sharing between countries and using different kinds of data.

To build, for example, a common picture of a battlefield during a conflict, we would also need consistent standards, data-processing platforms, manageable data volumes and, possibly the most difficult of all, policies for data and knowledge sharing between different countries, including how to address different sensitivities, equities and releasability.

Data management and accountability is a vastly underappreciated aspect of AI and, while the Five Eyes community has been working on this for some time, it remains one of the greatest challenges for collaboration. It will be critical in effectively monitoring a battlespace characterised by smart technologies such as AIs and drones and employing offensive cyber techniques.

Recommendation: AUSMIN should commit to developing standards for sharing battlefield data in a common picture, using existing Five Eyes programs as a foundation for streamlining processes.