This essay is from ASPI’s election special, Agenda for change 2019: Strategic choices for the next government. The report contains 30 short essays by leading thinkers covering key strategic, defence and security challenges, and offers short- and long-term policy recommendations as well as outside-the-box ideas that break the traditional rules.

The challenge

No country is more important to Australia than Indonesia. In 2019, Paul Keating’s now famous dictum, first enunciated 25 years ago, has assumed even greater salience as China emerges as a truly global power and regional political developments threaten to undermine Southeast Asia’s hard-won economic advances.

The biggest challenge for the incoming government in Canberra is to address the yawning trust deficit with Jakarta. Too often in recent years, our diplomatic relations with Indonesia have been blown off course by avoidable political squalls—the latest being the controversy generated by the Morrison government’s desire to relocate Australia’s embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

The aim must be to deepen and broaden Australia’s engagement with Indonesia and to build genuine trust and closer personal links, not just between our political leaders but within the broader community and within key counterpart government agencies and departments. With national elections to be held in both countries in the coming weeks or months, this year provides a suitable platform for a new resolution by Australia’s political leaders to pay greater attention to Indonesia and then deliver on that resolution in the next term of government. We need to work towards a stronger, deeper and more durable partnership with Jakarta.

For more than two decades, successive Australian governments have hyped the benefits of closer economic, political and cultural links with Indonesia. Our political leaders and our strategic policy planning documents continually pronounce on the importance of Indonesia’s economic rise for Australia. But mention of Jakarta lags far behind the considered treatment given to our major trading partners, led by China, the US and Japan. Geographical proximity doesn’t dictate closer economic relations.

The official rhetoric from Canberra has placed great store on Indonesia’s strong performance as Southeast Asia’s largest economy, citing its growing middle class and its rapidly increasing demand for goods and services. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s 2017 foreign policy white paper pointed to the likelihood that Indonesia, with its 260-million-strong population, will be the world’s fifth largest economy by 2030.

Yet Australia’s business and academic communities have signally failed to take up the challenge of greatly increased economic and educational engagement with our giant northern neighbour. Our trade and investment in Indonesia, never robust, has languished since the 1998 Asian financial crisis and in the wake of China’s remarkable economic ascension since the turn of the century. Australian companies still hold negative perceptions about the difficulty of doing business, given Indonesia’s uncertain regulatory framework and pervasive corruption. That needs to change before Indonesia becomes a major global economy.

Our two-way trade with Indonesia is currently flatlining at around $16.5 billion annually—accounting for just 2.2% of Australia’s overall global trade. Indonesia is only our 13th largest trading partner—lagging behind its much smaller ASEAN neighbours—Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia.

Since the mid-1990s, government-to-government ties have gradually developed into a dense web of activities including counterterrorism cooperation, financial sector governance reform and joint military exercises. Our embassy in Jakarta is now our largest overseas diplomatic mission; its more than 500 staff include 150 Australia-based diplomats. But deep functional working relationships (as we have built over decades with the US) need to be built between our respective defence organisations—and the defence industries that support them. A decades-long agenda needs to start now.

We have a fundamental stake in Indonesia’s continuing prosperity and political evolution as the world’s largest Muslim democracy and the natural leader of ASEAN. But, beyond the official rhetoric and closer bureaucratic partnerships that have been forged between government agencies since the 1990s, broader people-to-people engagement between Australia and Indonesia has barely advanced.

While Australia is still the largest destination for Indonesian students studying abroad, the number (currently around 40,000) hasn’t changed in years. Conversely, the number of Australian students undertaking Indonesian studies in our schools and universities, including language learning, is the lowest in decades.

We also continue to demonstrate a high level of ignorance about political developments affecting our northern neighbour. Many Australians still fear that Indonesia could pose a military threat to Australia. They also worry about the spread of militant Islam and refugee flows from the archipelago. A 2018 Lowy Institute poll found that only 24% of Australians agreed that Indonesia was a democracy.

On the Indonesian side, long-held popular stereotypes about Australia and Australians persist. According to leading Indonesian journalist Endy Bayuni, we’re still seen as ‘racist, arrogant, manipulative, exploitative and intrusive’. Many members of Indonesia’s political elite haven’t forgiven Australia for the role we played in bringing about East Timor’s independence in 1999. They also harbour deep suspicions about our intentions regarding the future of troubled Papua.

Quick wins

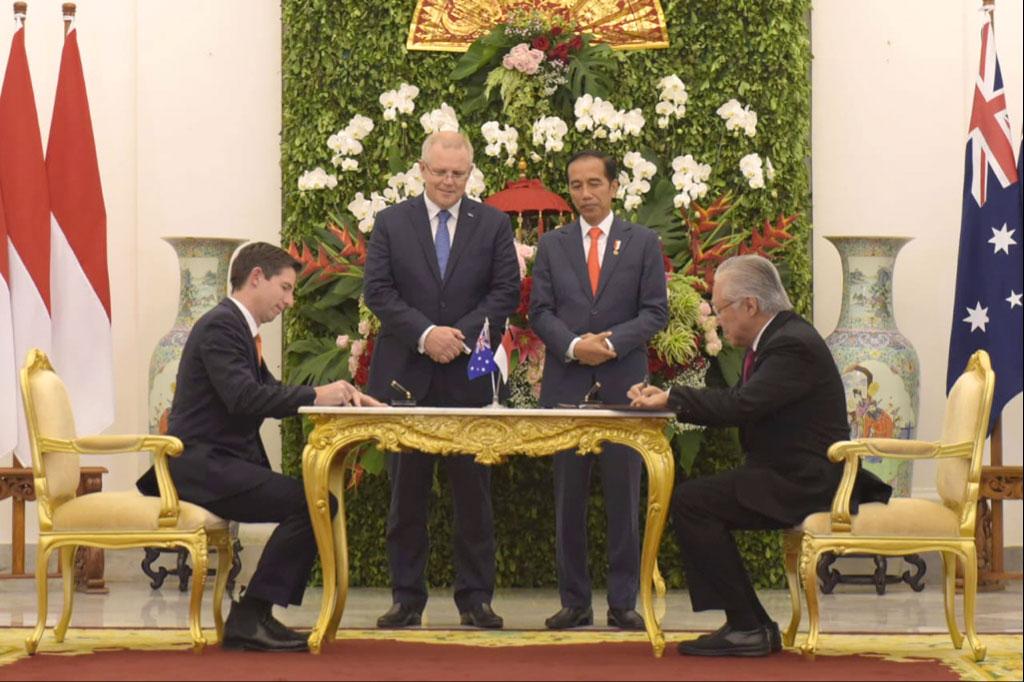

The incoming government in Canberra should move quickly to ratify the Indonesia–Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) agreed in August 2018 [to be signed today, though ratification could be months off—Eds]. The signing of this landmark trade agreement was stalled in the wake of the Jerusalem embassy controversy.

The CEPA promises to be a shot in the arm for Australian trade and investment in Indonesia, offering better access to our commodity exporters, including the agriculture and manufacturing sectors. Further trade liberalisation under the CEPA framework will enable Australian service industries to invest in areas such as education, telecommunications, health and mining.

Vocational training providers will be able to partner with Indonesian counterparts to provide skills training in Indonesia. Under the CEPA, Indonesia’s foreign investment regime will provide greater legal certainty for Australian companies seeking to invest in Indonesia. Economic opportunities need to be pursued by a more sympathetic and more Indonesia-literate business community. Indonesians also need to become more aware of what Australia has to offer, particularly in the services sector.

The hard yards

Only by pursuing a much deeper and broader engagement with Jakarta can we hope to bridge the gulf between two vastly different cultures. As Keating once observed, the Australia–Indonesia relationship needs to grow not only in the statements of governments but ‘in the attitudes and actions of ordinary Australians and Indonesians’.

The incoming government should consider a number of additional measures to help underpin a more durable partnership with Indonesia:

- Embark on a national mission to build a much broader understanding and awareness of Indonesia across the wider Australian community. This should include a major new investment in Indonesian studies and language courses in our schools and universities using federal government funds flowing to state governments.

- Expand government-to-government dialogue with Jakarta to include regular meetings between economic ministers and officials.

- Continue to develop Australia’s diplomatic footprint in Indonesia, including by opening a consulate in Sumatra.

- Maintain and refine our $300 million aid program with Indonesia, with an emphasis on capacity building and strengthening direct links with Indonesia’s civil institutions involved in areas such as natural disaster relief.

- Widen defence and security cooperation, with a sharp focus on cyberwarfare, maritime surveillance and counterterrorism. We should eventually mount joint aerial surveillance and naval patrols across designated zones in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. Deepening institutional relationships between our defence organisations, so that Indonesians and Australians know and work with their counterparts, from logistics to personnel, as well as between service formations, is key to a defence partnership that works and which leaders value.

- Strengthen formal collaboration between the national and provincial parliaments of both countries with annual exchanges by delegations of MPs. Building these institutional links will help bolster Indonesian democracy, including religious tolerance and support for ethnic minorities.

In 2019, Indonesia remains an enigma. The world’s fourth largest nation is seemingly incapable of assuming its destiny as the leading power in Southeast Asia. In the Jokowi era, Indonesia has become even more insular, nationalistic and illiberal.

Australia must seek a greater strategic accord with Jakarta, not least because of our geography and history. We were there at the beginning, supporting Indonesia when it declared its independence in 1945. The archipelago will always guard our northern approaches.

The paradox of the bilateral relationship is that, notwithstanding recurrent political crises over 60 years, our most important regional diplomatic initiatives in recent decades, including the Cambodian peace settlement and the creation and evolution of APEC and the ASEAN Regional Forum, were accomplished only by working in close partnership with Jakarta.

Breaking the rules

The incoming government should consider three major initiatives to strengthen the bonds between Australia and Indonesia:

- Establish an Australia–Indonesia Climate Change Commission. This body would see scientific experts from research institutes in both countries collaborating in diverse areas such as agriculture, fisheries and forestry to mitigate the effects of climate change in both countries.

- Create an annual Track 2 dialogue convened and run by Indonesian and Australian business figures. The aim would be to strengthen bilateral business networks, with a particular focus on the services sector.

- Mobilise the Australian university network to establish campuses in Indonesia, with a focus on training Indonesian students in applied science and technology.