The 2023 defence strategic review noted that Australia’s economy had become more interconnected with the Indo-Pacific and the world, and that brought a fundamental interest in protecting the rules-based order upon which international trade depends.

The DSR also said that ensuring the uninterrupted flow of maritime commerce underpinned the importance of resilience as a vital component of Australia’s deterrence-by-denial strategy. The DSR argued that the navy must be optimised to operate in Australia’s immediate region, and to secure sea lines of communication and maritime trade.

The DSR defines Australia’s primary area of military interest as encompassing the northeastern Indian Ocean through maritime Southeast Asia and into the Pacific, including Australia’s northern approaches.

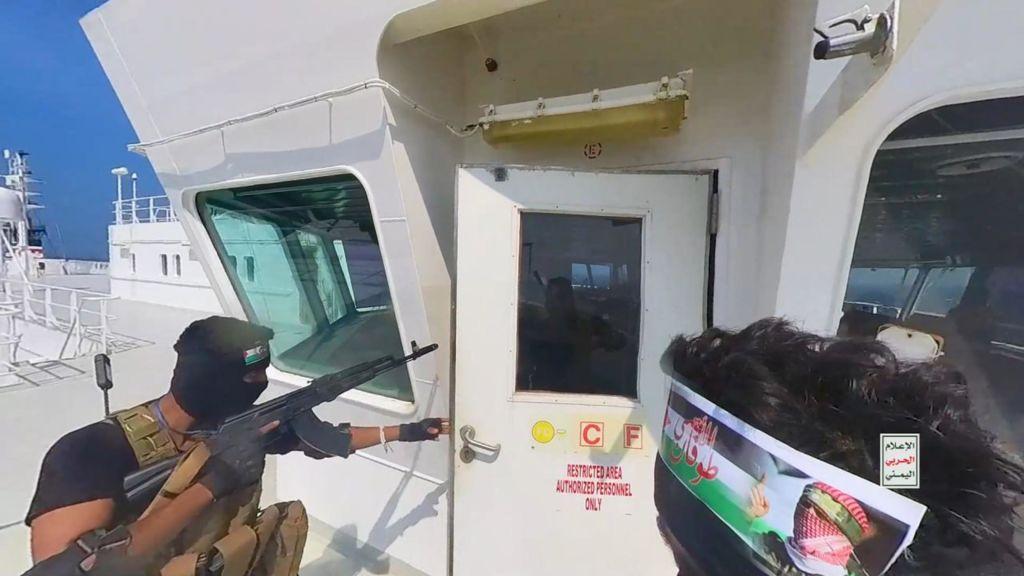

The focus on the Indo-Pacific is entirely understandable given the growing challenge presented by China, but it raises the risk that Australia may fail to respond adequately to events further afield that could undermine its security. This has been demonstrated by the attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea launched by Iranian-backed Houthi forces since 7 October when Hamas, also backed by Iran, carried out its vile terrorist attacks on Israel.

These attacks pose a serious threat to trade. More than 12% of global maritime commerce passes through the Red Sea and its exit to the Indian Ocean, the Bab el Mandeb Strait.

A failure to respond would not only imperil global trade but also weaken a rules-based order already under attack from authoritarian states, with Iran a key belligerent.

The US responded decisively, establishing Operation Prosperity Guardian with a multi-national naval taskforce to protect shipping. The UK, Bahrain, Canada, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Seychelles and Spain have so far joined the operation. Australia signed a joint statement condemning the Houthi attacks and, as a maritime nation that has long understood the importance of unencumbered sea lanes, there was a reasonable expectation that it would send a warship to join the taskforce.

The media reported that the US, Australia’s most important strategic and security partner, asked Canberra to send a ship but that request was declined. It is understood that the US then asked Australia to send additional personnel to the US-led Combined Maritime Forces headquarters in Bahrain. While some will praise or justify the response as a demonstration that Australia’s priority is the Indo-Pacific, this fundamentally misses the global nature of maritime security and the fact that the world can no longer be easily compartmentalised into Europe, the Middle East and the Pacific. The global impacts of both the Israel–Hamas war and Russia’s war on Ukraine clearly show this.

Australia cannot seek immunity through inaction. And we can’t expect support for stability and security in the Indo-Pacific from our American and European partners if we leave the rest of the world to others.

The government’s contradictory stance suggests that the DSR constrains the Australian Defence Force’s ability to respond to challenges beyond what’s defined as Australia’s area of primary military interest. The DSR is correct to narrow Australia’s strategic focus, and it would be foolish to be dragged into an open-ended deployment in another Middle Eastern war when the main challenge, from China, is increasing in our region.

However, Operation Prosperity Guardian is not a long-term deployment ashore with ground forces, and the requirement for the ADF to help protect maritime trade is clear. While the ADF should prioritise the defence of sea lanes in the Indo-Pacific, the reality is that an adversary can block trade outside this region and the effect is still the same.

So, does the ADF, and the navy in particular, fail in its mission to protect trade simply because it’s threatened in an area outside an arbitrary definition of what constitutes Australia’s primary area of military interest?

The globalised world means it’s difficult to simply divide areas of responsibility and concern into narrow geographic zones when trade, physical and informational, defies geography. The gathering threat to the liberal international order and the free flow of commerce posed by an axis of authoritarian states can emerge at any time and anywhere—from the high seas, to space and cyberspace. Failing to meet that challenge cedes the advantage to the opponent, making future threats more likely. The government’s argument that this request falls outside Australia’s primary area of military interest reflects a failure to understand a globalised threat to a globalised world.

Even though the US and Australia are firm allies, and the relationship has grown under the Biden administration, the refusal by the government to send even a single warship will be noted in Washington. It’s impossible to know how the relationship between Canberra and Washington may evolve under a new administration with, potentially, a radically different foreign policy agenda after 2024. The passing by Congress of the US National Defense Authorization Act reinforcing progress on AUKUS provides grounds for optimism, but Australia’s failure to support the US in an important mission to safeguard freedom of navigation and maritime commerce won’t be quickly forgotten.

This is not to say that Australia doesn’t have agency or that it should automatically agree to any US request. Australia should always make decisions in its national interests and, despite misleading suggestions otherwise, AUKUS has strengthened not weakened our sovereignty. But this rejection is not about deploying to war or taking our eyes off the threats in the Indo-Pacific.

Joining a multi-national taskforce to protect shipping lanes and the principle of freedom of navigation would clearly be in Australia’s interest. We would call for such multi-national action if attacks occurred in our region. And if potential threats in the Indo-Pacific are so serious that Australia can’t afford to provide a single ship to the Red Sea taskforce, that might suggest that the messaging about the situation in the Indo-Pacific underplays the reality, including Beijing’s bullying and intimidation of countries like the Philippines.

While good strategy always involves making wise choices on employing limited resources to achieve policy goals, any inability to respond to multiple and diverse threats—from Houthi terrorists or the People’s Liberation Army Navy—implies that Australia needs to get serious about building up naval capability more rapidly.

The navy has assured the government it can deploy a warship to the Red Sea if asked to. But any deployment would require rotations of ships and crews, placing additional strain on the navy’s readiness for other tasks. The surface combatant review is now with the government, and no comment on it is expected until the first or second quarter of 2024. If the decision not to deploy a ship to the taskforce is based on concerns about Australia’s fleet size and readiness, then a larger and more powerful navy is clearly needed to respond to the growing risks within our area of primary strategic interest and, if necessary, beyond.

Ideally, this should involve a larger fleet of warships with greater firepower that can operate at greater range—but also higher fleet readiness and sustainability for protracted and diverse operations. That means expanding the workforce to crew and sustain a larger and more powerful navy.

The situation demands an increase in defence spending, sooner than planned, to meet increasingly clear challenges that may not wait.

These challenges are not limited to one part of the world. China, Russia, Iran and North Korea are all undermining the international rules to which Australia owes its security and prosperity. Australia must play an active role in supporting these rules and deterring those who would remake them in their own malign interests.