Treasury has stepped up enforcement of Australia’s foreign investment regime, however it continues to try to balance protecting national interests and encouraging investment inflows.

Data suggests some foreign investors, noting national security provisions in the system, are choosing other destinations for their money or keeping it at home. Chinese investors remain notably unenthusiastic about Australia.

The latest quarterly report on Australia’s foreign investment shows Treasury issued 16 infringement notices for non-compliance with conditions in the December quarter, up from only one in all 2021–22 and none at all in the previous financial year.

Treasury gets a fairly steady stream of referrals from government agencies and the public over potential non-compliance, with 48 received between July and December last year and 114 in 2022–23.

In the first half of 2023–24, Treasury approved 616 investment proposals worth a total of $86.7 billion (not including residential real estate). That was roughly in line with 2022–23, when 1310 proposals worth $171.5 billion were approved over the 12 months.

However, the number of proposals withdrawn reached almost a quarter of the numbers approved. This was double the rate of withdrawals over the previous two years and may point to growing difficulty in winning official approval.

Although Treasury provides no explanation for investment proposals being withdrawn, a common reason is that investors are told their proposals will not be approved or may require unacceptable conditions or restructuring.

About 75 percent of approvals by value are made subject to conditions, which may relate to tax structuring, board representation, data security or deadlines for developing projects. Companies pay hefty fees to submit a foreign investment proposal for approval.

Following a 2021 toughening of national security provisions in the foreign investment legislation, investors in specified sectors must seek Foreign Investment Review Board approval even if investments are below the mandatory review thresholds.

In the half year to December, only 29 proposals worth a total of $600 million were approved under the new national security provisions. Just three were made subject to conditions.

This is a sharp fall from the previous two years and suggests the new national security provisions may be deterring investment. In 2022–23, the FIRB approved 110 proposals worth $5.7 billion under the national security provisions, while in 2021–22, there were 119 proposals worth $10.1 billion.

Australia’s foreign investment screening has become much more rigorous over the past decade, with far greater involvement of the national security agencies and the Australian Tax Office and imposition of significant application fees designed to fund monitoring and compliance. There were big legislative overhauls in 2015 and 2021.

Foreign investment lawyers say increasingly onerous requirements are a disincentive to investment. This year’s budget included measures to ease compliance obligations for ‘low risk’ investors—the example given was Canadian pension funds—and also offering fee refunds to investment proposals that were not approved.

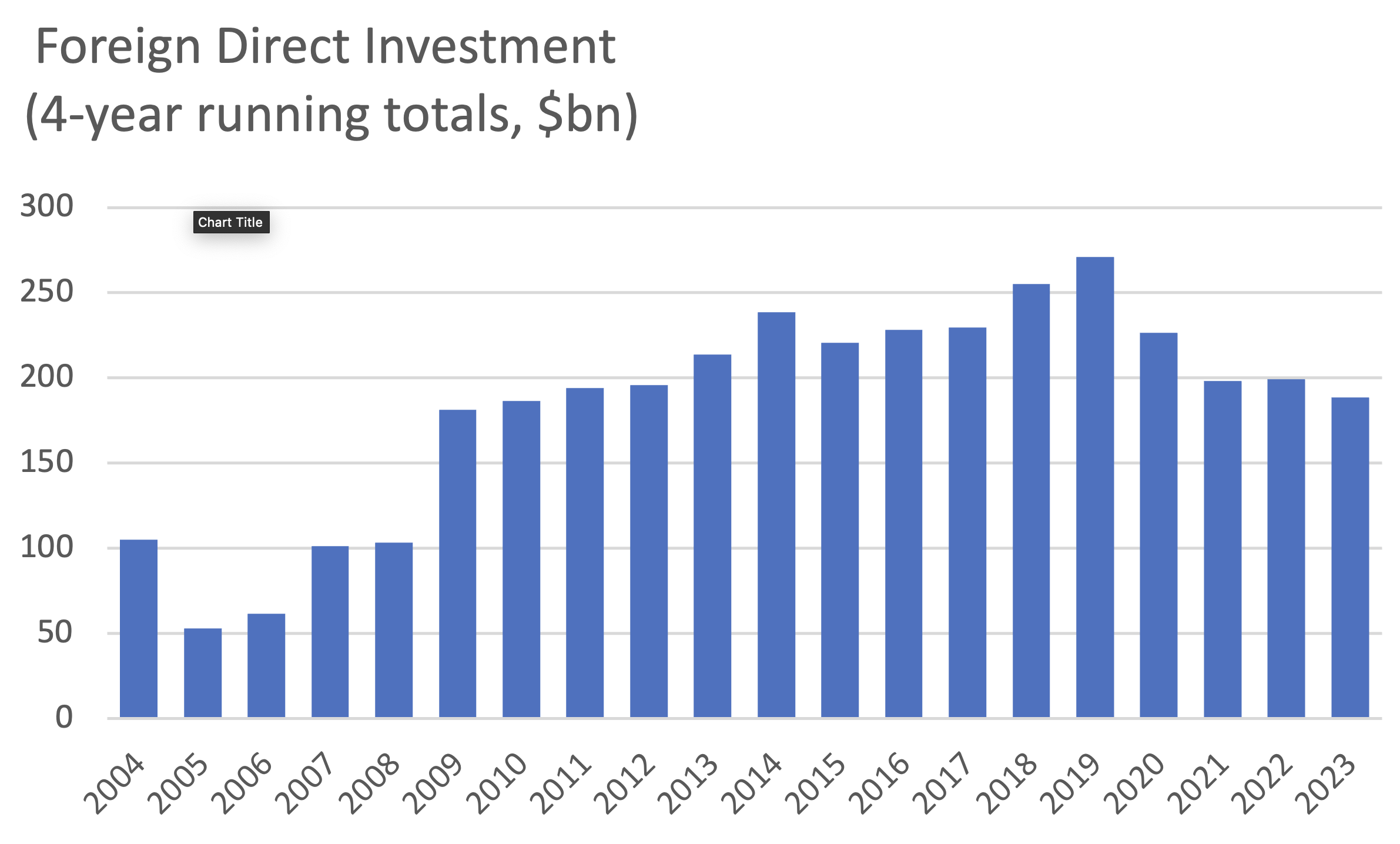

The actual flow of foreign direct investment into the country (as measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, rather than the FIRB, which tracks only new proposals) bounces widely from one year to the next, but a four-year trend suggests Australia is becoming less attractive to foreign business.

The $189 billion of foreign direct investment from 2020 to 2023 was the lowest since the four years to 2010 and 30 percent down from the peak four years of 2016 to 2019. (This includes only direct investment by foreign companies and excludes portfolio investment by pension funds and other institutions.) While the latest period includes the pandemic, investment flows last year were little more than they were in the heart of the 2008–09 global financial crisis.

There are many possible reasons for the decline besides the screening regime, starting with Australia’s 30 percent corporate tax rate, compared with an OECD average of 23.6 percent.

The annual World Investment Review from the United Nations Commission on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows Australia is not alone in managing the tension between encouraging investment for economic reasons while trying to protect sectors of national importance, including security-related concerns.

Australia has screened foreign investment since 1975 and for decades was almost the only country to do so. UNCTAD records that in 1995, only three countries screened foreign investment. By 2011, 10 countries had adopted foreign investment screening while the latest UNCTAD report shows 37 nations now vet foreign investment proposals for national security risks, with eight more in the process of introducing screening. The OECD says the Australian regime is still one of the world’s most restrictive, second only to New Zealand.

The rising sensitivity to potential threats from foreign investment is the product of an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment and emerging doubts, particularly in the developed world, about benefits flowing from globalisation. UNCTAD’s latest report comments that ‘global economic fracturing trends, trade and geopolitical tensions, industrial policies affecting strategic and manufacturing sectors, and moves by corporates to diversify supply chains are reshaping international production and FDI patterns’.

UNCTAD data shows that apart from the 2020 pandemic year, the US$1.3 trillion in global foreign direct investment last year was the lowest since 2010, while there has been no underlying growth in global investment flows since the years preceding the global financial crisis. UNCTAD reports that foreign direct investment last year would have shown a 10 percent fall but for corporate restructuring forced by the new global minimum tax regime.

It is possible that this tax restructuring contributed to the sharp fall in foreign direct investment in Australia last year, which dropped from $91 billion to $45 billion. Swiss, Canadian and Dutch companies pulled large sums out of Australia last year while the three biggest investors—companies from the United States, Britain and Japan—all continued to increase Australian holdings.

US firms poured a record $35.8 billion into Australia last year, reversing the losses that occurred following the Trump administration’s tax changes designed to encourage firms to repatriate investment. US firms withdrew a net $22.3 billion in 2020 and 2021.

Investment from China remains weak. In 2022, Chinese firms withdrew a net $3.3 billion from Australia while their new investment last year was only $873 million, according to the ABS. China’s accumulated investment in Australia stands at $88 billion, which ranks it 10th, behind the Netherlands and Canada but ahead of New Zealand. US investment in Australia by contrast is approaching $1.2 trillion, while Britain has 10 times as much investment in Australia than China has, at $879 billion.

Australia has always claimed a much larger share of global investment flows than its economic size would suggest. In 2022, Australia was ranked seventh, just behind France and Brazil, attracting foreign direct investment flows equivalent to 4.6 percent of the global total. Inflows last year dropped Australia’s ranking to 12th and its global investment share to 2.7 percent.

The actual flow of foreign direct investment into the country (as measured by the

The actual flow of foreign direct investment into the country (as measured by the