Australia’s aspiration for the South Pacific must be for the creation of an economic, political and security community. Australia and New Zealand will be central to such a community—and will carry the cost—but much of the head, heart and soul will come from Papua New Guinea and the other members of the Pacific Islands Forum. And in this rendering of the ‘islands’, Timor-Leste has to belong.

At its most ambitious, the community would have a common currency based on the Oz dollar, a common labour market, and common budgetary and fiscal standards. Integration of that magnitude will take decades, given the huge challenges the islands face. This community model is discussed in detail by the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee in its 2003 report A Pacific engaged with its vision of a ‘Pacific economic and political community’. Here’s the committee’s first recommendation:

That the idea of a Pacific economic and political community which recognises and values the cultural diversity in the region, and the independent nations within it, and takes into account differing levels of growth and development, is worthy of further research, analysis and debate. Such a community should be based on the objectives of:

- sustainable economic growth for the region;

- a democratic and ethical governance;

- shared and balanced defence and security arrangements;

- common legal provisions and commitment to fight crime;

- priority health, welfare and educational goals;

- recognition of and action for improved environmental standards; and

- recognition of mutual responsibility and obligations between member countries of the community.

Over time, such a community would involve establishing a common currency, preferably based on the Australian dollar. It would also involve a common labour market and common budgetary and fiscal standards.

I’m proud to have a copy of that report, signed by the committee chairman, Senator Peter Cook, with his dedication saying that I had a lot to do with its recommendations. My submission certainly called for a grand vision of community. But it also argued that community creation isn’t merely Australia offering favours—it’s a core expression of Australia’s interests and history and strategic needs. There’s always lot in it for us.

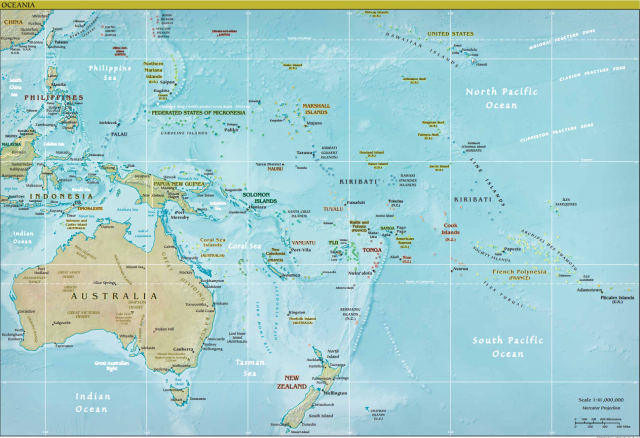

In the earlier era of empire, the Oz ambition was to rule a region called Australasia. These days, the community is a much easier sell wearing the Oceania moniker. The geography endures as our understanding shifts.

Both sides of Oz politics are promoting community ideas: ‘integration’ from the Coalition government and a Pacific ‘pledge’ from Labor. The Turnbull government’s foreign policy white paper offers the South Pacific economic and security integration. The policy states that integration is ‘vital’ to the Pacific.

Labor’s shadow defence minister, Richard Marles, calls for Australia to make a ‘pledge’ to the islands based on a deeper defence relationship and the offer to ‘assist the functions of government in the Pacific’.

The argy-bargy about China’s aid to the South Pacific saw two sets of interests collide—Australia’s view of itself as the South Pacific leader versus the inevitable arrival of China. Canberra’s snarkiness has plenty of downsides, yet there’s some upside if it pushes Australia to lift its game. The Oz strategic denial instinct is a constant with a 150-year history. The frisson of fear from the foreign bogey always forces us to focus.

Australia has a role in talking about the best use of aid. We’re the region’s biggest donor, and we’ve got the scars from quietly burying our share of white elephants; we know how hard it is to do good aid, because we’ve delivered much that didn’t work.

Oz bitching at Beijing, though, is poor tactics because we’re also blaming the islands. Much better to let island governments lead the discussion, and then weigh in via regional organisations. The Pacific Islands Forum has an important role in promoting understanding about the good and bad of aid. And the Pacific Community (the old South Pacific Commission) offers valuable technical expertise, plus it draws in other important players such as the European Union.

Accepting that China is in the South Pacific to stay—and it is—then it has plenty to offer. China can listen and can be persuaded. The best geopolitical news for the region last decade was the ceasefire between China and Taiwan in their fight over diplomatic recognition in the South Pacific. The destabilising impact of that chequebook diplomacy was dramatically displayed in Solomon Islands in the riot and razing in the heart of Honiara after the 2006 election.

The freeze on diplomatic competition was all about the China–Taiwan relationship, but in agreeing to diplomatic detente they responded to sustained protests from Australia and the South Pacific about the appalling cost of their contest. China can throw its weight around and do damage; that calls for lots more talking by the region and better regionalism.

Building a Pacific community strengthens the islands just as it serves Australian interests. The geopolitical contest is getting ‘crowded and complex’, as Joanne Wallis outlined in her 2017 ASPI paper. Wallis also last year published a fine book, Pacific power? Australia’s strategy in the Pacific Islands, which spent a lot of time considering the question mark in the title. But she offered a succinct rundown of Oz power:

Australia is larger and has vastly more material resources than Pacific Island states: it represents 94.5 per cent of the region’s gross domestic product (GDP); 98 per cent of defence and security spending; 60 per cent of population; and contributes 60 per cent of all development assistance.

Australia has the means to build a community with its neighbours. Do we have the imagination and the will?