The Australian Liberal-National opposition’s proposal to build nuclear power stations on the sites of old coal-fired plants is misguided. The policy would perpetuate Australia’s concentration of electricity generation and worsen our vulnerability to air and missile attack.

Renewable-energy installations, by contrast, are numerous, dispersed and therefore much less profitable for an enemy to destroy. They’re also far easier and quicker to fix. And energy storage capacity, another source of resilience, necessarily grows as they’re built.

The current concentration of large slabs of generation capacity in coal-fired stations is already a vulnerability. They’re attractive targets. A single attack by a few strike missiles might knock out a plant and its large chunk of power supply.

Chinese bombers, submarines and carrier-launched aircraft could attack them using guided bunker-busting bombs, regular air-to-ground missiles or hypersonic ones with tungsten penetrators. Russia is indeed targeting power stations in its war against Ukraine, typically hitting them with missiles and drones.

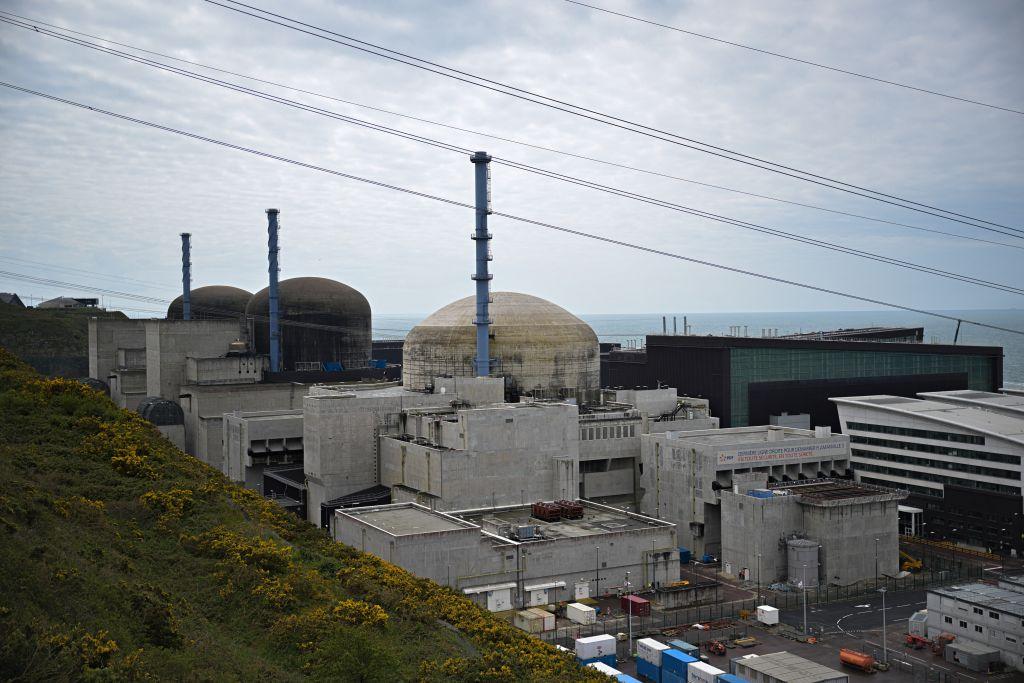

If a big power station’s energy comes from nuclear reactors instead of boilers burning fossil fuel, a strike could cause an environmentally devastating release of radioactive material. If we had nuclear power stations, they would in fact be things that an enemy could use against us.

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster resulted in radioactive contamination of about 150,000 square kilometres reaching as far as 500km from the plant. It released more radiation than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. In 2007 the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies reported: ‘a nuclear power plant contains more than 1000 times the radiation that is released in an atomic bomb blast’. The Chernobyl experience suggests that destruction of a large nuclear station on the site of the Eraring coal-fired plant in New South Wales might render the port of Newcastle inoperative and perhaps force the evacuation of 800,000 people in the city and Central Coast.

Most of Australia’s coal-fired power stations are in NSW, Victoria and Queensland. Replacing at least some with nuclear plants, as the opposition suggests, would therefore expose much of the population to frightening wartime risk. Attacks could result in long-term crippling of the economy by rendering cities uninhabitable. They would raise the cost to Australia for continuing any war.

Fixing a coal-fired power station that had suffered war damage would be hard enough and would take many months, at least. Fixing a nuclear one would be a lot harder and take much longer. For all that time, the economy would be deprived of the plant’s generating capacity.

Wide distribution of electricity generation to hundreds of wind and solar farms avoids such risks. Collateral damage from strikes on them would be small, not least because they are usually in remote places.

Because renewable generation capacity is economically divided among many installations each with modest capacity, they raise an enemy’s cost of knocking down supply. Eraring’s capacity is 2880 megawatts, concentrated in a 400-metre-long line of four generating units, each of which might be disabled by a single hit.

The Macintyre wind farm in Queensland, to be completed this year, will have 180 wind turbines, a site area of 36,000 hectares and a rated capacity of 1026 megawatts. Average output of a typical Australian windfarm, allowing for variation in wind strength, is only about 35 percent of rated capacity. But destroying such an installation would require a great many munitions.

Similarly, the solar farm at Coleambally, NSW, has more than 565,000 solar panels spread over 513 hectares and a rated capacity of 150 megawatts. At the time of completion, its output was expected to average 45 megawatts.

Moreover, generating farms are complemented by homes and businesses that are partly or entirely independent of grid supply thanks to their own solar generation and battery storage.

In World War II, Japan had a dispersed electricity-generating system, which was one reason why the United States did not try to knock out supply. The system consisted of too many targets and would have been too hard to debilitate.

Repairability enhances the inherent robustness of renewable generation. Critical parts that are not made domestically would need to be stockpiled, something that Japan did in preparation for World War II. The federal government’s Future Made in Australia strategy will help. If Australia builds wind turbines, solar panels, batteries and distribution gear, it will have plenty of skills and fabrication machinery for fixing them. Recovery times would be far shorter than for a damaged or destroyed nuclear plant.

The opposition’s nuclear power proposal would lead us into far greater vulnerability in a war with a major adversary. It’s much better to stay on our current course. Every time a new piece of the renewable energy system is switched on, we become a little less vulnerable.