This is the fifth in our series ‘Australia in Space’ leading up to ASPI’s Building Australia’s Strategy for Space conference in June.

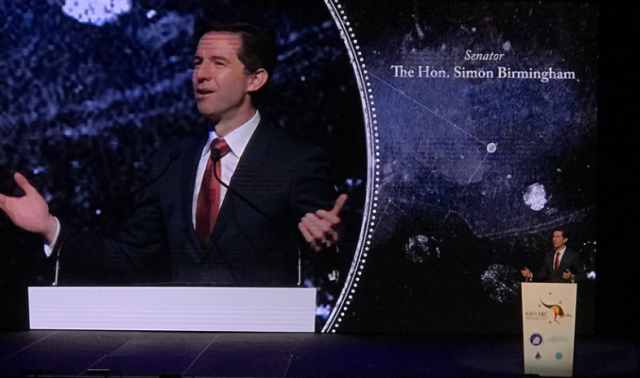

In September 2017, the Minister for Education and Science, Senator Simon Birmingham, announced that the Australian government would establish a space agency in 2018. The announcement was made to the global space community at the opening ceremony of the 68th International Astronautical Congress (IAC2017) in Adelaide.

Australia had a space agency from 1987 to 1996. Called the Australian Space Office (ASO), it was established by the Keating Labor government. Shortly after the Howard Coalition government came to office in 1996, the ASO was axed. The ASO and associated programs failed for numerous reasons, not the least of which was the ambivalence shown by Defence towards the office and its responsibilities.

The question now is whether the new agency will fare any better. There are three causes for optimism:

- There’s bipartisan support for the new agency.

- There’s much broader community awareness of the dependence that we all have on secure and assured access to services and data provided by satellites.

- Defence is engaged and supportive.

A reasonable expectation is that the agency will be funded and staffed to perform a series of essential tasks. It may also be funded and staffed to perform some discretionary tasks as well. The essential tasks relate to governance and regulation, nationally and internationally. They include:

- administering the Space Activities Act

- providing a degree of coherence and explicit coordination to the Australian government’s own investments in space capabilities

- representing Australia’s space interests at international forums devoted to space matters, including the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

Four discretionary tasks that the agency might perform are:

- support for domestic space industry development in both upstream (space) and downstream (ground-based) elements

- support for space science and engineering research

- promotion of STEM education programs, using space topics as a learning vector

- development of public outreach programs that promote a better understanding of the outer space environment and of Australia’s interests and activities among the broader public.

The extent to which the new agency does involve itself with these matters will be a test of the real priority accorded to space matters, beyond the rhetoric and commitments made at IAC2017 by the government.

The agency is essential to the development of a domestic industry, but on its own will not be sufficient. Industry, including large companies, will need to step up and invest, and that won’t happen unless companies can see a path to profit within a reasonable period of time.

In recent years several small companies seeking to engage in upstream space activities have been founded in Australia. They’re taking advantage of technological changes, including the miniaturisation and commoditisation of electronics, sophisticated software, and new materials and manufacturing techniques to develop niche products and services. The commercial success of these companies will be determined by the extent to which they are successful internationally. The Australian market may nurture their development but isn’t large enough to ensure long-term and sustained success.

Furthermore, space companies seeking to develop technologies in Australia may well find their access to export markets limited by Australia’s export regulations, which are restrictive where space technologies are concerned. Export facilitation may become one of the most important roles of the space agency in support of the Australian space sector if the sector is to flourish.

Australia’s space engagement since the 1940s has been shaped by the country’s geography (location, size and population distribution), and tied to national security interests. Initially, Australia established Woomera to support the ambitions of the United Kingdom to develop long-range missiles. Since the 1970s Australia has hosted ground stations that support missile early-warning and intelligence gathering satellites vital to the security interests of the United States. More recently, Australia has installed ground-based sensors at North West Cape that contribute to the space debris monitoring system of the United States.

Defence and national security interests, at the heart of which is Australia’s alliance relationship with the United States, will be the dominant policy driver for Australian space activity for the immediate future. The bulk of the Commonwealth’s space investments are in Defence, notably a $3–4 billion investment in space-based remote sensing announced in the 2016 Integrated Investment Program.

The Australian Defence establishment is seeking to understand outer space both as a domain from which to influence maritime, land, air and cyber warfare, and as a warfighting domain in its own right. To acquire knowledge and understanding, even before contemplating space operations, Defence is making modest investments in cubesats. A civilian program is a helpful adjunct to these activities.

Australia’s geography will continue to be attractive and important as a location for ground stations from numerous nations, including the United States. Although Australian relations with China and Russia are presently strained, both may seek to install ground infrastructure in Australia in support of their space activities in future.

Ukrainian groups are known to be interested in an Australian launch site, and Brexit may also lead, in time, to closer cooperation with the United Kingdom on space projects. These possibilities may present opportunities for Australia to exercise middle-power influence in the space domain in its own interests and those, more broadly, of the global rules-based order.

Space technologies and capabilities are profoundly ‘dual use’. The new agency, by promoting civil and commercial opportunities, will establish a basis for defence-related space capabilities for the foreseeable future. There’s a risk that the potential of so-called ‘Space 2.0 technologies’ will be overstated by some who would put them at the core of an emergent Australian space sector. New jobs and innovation in the Australian market are more likely to occur downstream in the data processing and application domains than in the upstream satellite segment, which is where Space 2.0 technologies are concentrated. As a consequence, the new agency may face a significant challenge in managing expectations.

The most immediate challenge, however, will be to find a cadre of women and men who have the standing, connections, skills and knowledge to turn the rhetoric of the Minister’s announcement at IAC2017 into reality.