Australia’s economic future: the challenge of reform

Posted By Peter Harris on July 24, 2015 @ 06:00

In the absence of significant new reforms by governments—both Federal and State—aimed at expanding opportunity and innovation, the outlook for Australia’s national income growth over the next decade is bleak.

The basis for this conclusion is simple:

- productivity is, over time, the key determinant of national income, as per Paul Krugman’s famous dictum: in the long run, productivity isn’t everything but it’s almost everything

- there’s good evidence in western countries, including Australia, that a secular slow-down in productivity has occurred over the last decade

- at the same time in Australia, there’s also a strong slow-down in national income due to our declining terms of trade (the relative prices of exports to those of imports)

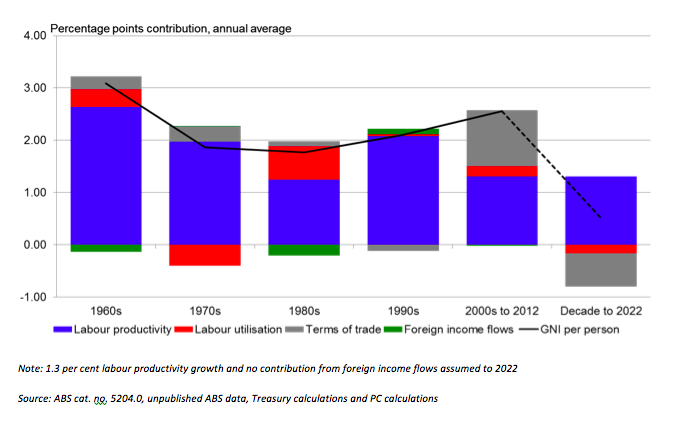

What this means is that for the next decade, we face a clear shift downwards in income growth, perhaps to half of the level that this economy has been used to over the past fifty years.

Contributions to growth in average incomes – stagnant labour productivity and poor national income growth (ie same growth as 2000–2012)

[1]The improvement will still be small even if labour productivity returns to long run levels in this decade from its relatively poor growth in the 2000s. We need a productivity surge.

[1]The improvement will still be small even if labour productivity returns to long run levels in this decade from its relatively poor growth in the 2000s. We need a productivity surge.

And there are other pressures. Depending on how rapidly baby boomers choose to retire, workforce participation—the number of us aged 15 to 64 who are employed—which is already showing signs of decline, will worsen at some point. Once established, this trend may not reverse itself, absent policy action and change in employer attitudes, for the next thirty years or so.

Of course, some of us will still prosper. There will be some income growth. But it’s likely that more of us can’t expect to enjoy rising real incomes. And the competition for a share of our slower-growing wealth could be a corrosive social issue if poorly-handled.

Alternatively, we could move to recognise this new reality and try to offset it with other policy initiatives.

Monetary policy and the actions of the Reserve Bank may not have much more scope left to offset these trends; interest rates are historically low. And fiscal policy remains beset by arguments over when to return to budget surplus.

This leaves microeconomic reform, a term which includes all manner of changes to the structure of our economy, who pays for the things we want, and which level of government offers greatest efficiency gains to delivering those things.

A generation ago, we faced a similar challenge, although the driving forces were different.

We chose to respond not by adding to the fiscal burden by borrowing, nor by over-reliance on monetary policy, but by wholesale economic reform, industry by industry, involving a comprehensive examination of both the traded and non-traded sectors of the economy.

Over more than a decade and across multiple changes of government—State as well as Federal—we pursued change and excluded no significant sector.

Economic Statements were a vehicle for change from 1987 until 1999. Because so many sectors were addressed together, each successive Statement reinforced two things:

- change was a shared responsibility and

- there was no escaping change, regardless of what business you might be in.

It’s my contention that this period of change altered expectations across the Australian economy.

It was no longer possible to be protected by government from the consequences of poor decision-making at the corporate level, nor was it easy to exploit market power—for union or for employer. Boards changed their approach to investment and innovation, and unions took opportunities to improve the lot of workforces by aligning better with investment plans.

Expectations are very powerful. They are, after all, a key driver of the effectiveness of monetary policy. And the famous US dictum ‘don’t fight the Fed’ indicates how powerful expectations can be.

Of course, there are many factors beyond the efforts of governments to reform that create the economy and society we have today.

But government is a crucial swing factor. It can choose to intervene, or to stand aside. If it chooses inaction, there’s an implicit signal that all will be right, eventually. And perhaps it will. Not always must government be part of the solution.

But the nature of the challenges listed above—lifting productivity, improving our terms of trade and addressing the issue of our ageing population—suggest there’s a vital role for government.

And it’s in managing Australia’s long-term economic trajectory that government has a core responsibility as well as a natural advantage—its ability to assess risks which are simply beyond the scope of other actors in our society.

We need governments to collectively choose to contribute via new policy approaches aimed squarely at real reform—in trade policy, energy policy, industrial relations, transport, planning, saving, as well as essential government-supported services like health and aged care.

These measures won’t always link directly to improved productivity and income statistics. But they offer a genuine opportunity for innovation and adaptation that’s our best chance to arrest a downward shift in Australia’s national income.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /australias-economic-future-the-challenge-of-reform/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: https://aspistrategist.ru/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Screen-shot-2015-07-23-at-7.28.15-PM.png

Click here to print.