The 2020 defence strategic update has been a welcome first step for many who see Australia’s place in the world and our region become increasingly insecure. Beijing’s recent demonstration of its willingness to leverage its economic weight to punish unwanted behaviour has contributed to existing anxieties about Chinese military expansion in the South China Sea and the wider region.

China’s rise has coincided with the apparent decline of Asia’s regional security guarantor. With the United States’ once unassailable political, economic and military power now looking like it will be seriously tested in the decades to come, the plan to upgrade Australia’s own deterrence capabilities laid out in the update seems eminently desirable, if not entirely necessary. However, there’s little point in investing heavily in the development and acquisition of those capabilities if the ‘other elements’ of national power mentioned in the update are neglected.

This leads to the question of an Australian grand strategy—an approach to policy development that ties all available elements of national power to a unified end goal. This concept is particularly relevant to our defence and foreign policies as, by their nature, they have a symbiotic relationship. Ineffective foreign policy will obfuscate military-strategic aims, and defence policy formulated in a silo runs the risk of neglecting non-military means of exercising power. The development and application of a grand strategy addresses this problem.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the grand strategy of the Monroe Doctrine formed the basis of the US approach to defence and foreign affairs in relation to European territorial encroachment. The end result was the dominance of the US across not only the Americas, but also the Pacific as the doctrine’s geographical boundaries widened.

While the 2020 update has clarified what Australia’s strategic approach to defence policy will be over the next decade, we are yet to see an equivalent (and unified) strategic product from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Australia’s most recent foreign policy white paper was released in 2017 and, much like the 2016 defence white paper, was a reflection of a strategic environment very different from today’s.

In the past five years alone, Australia’s diplomats have had to navigate the challenges of an increasingly aggressive Beijing, political instability among some of our closest allies (and the trade repercussions of that instability), and now the worst global pandemic in a century. Despite these increasing challenges, the federal government hasn’t given DFAT the same amount of funding attention as Defence.

In December 2019, it was reported that since the current government was elected in 2013, Australia’s total diplomatic and development budgets have fallen from 1.5% of the federal budget to 1.3%, which stacks up poorly against comparable countries, such as Canada, which spends 1.9% of its federal budget on diplomatic and development efforts. More recent news of job losses at DFAT only weeks after the defence update was released act as a warning sign that the government has been focused on defence capability and acquisition while neglecting its diplomatic corps.

The reality is that defence capability is not the only method of power projection, nor is it always the most effective. Australia’s diplomatic efforts have projected influence across the world further and more effectively than our military capability can on its own.

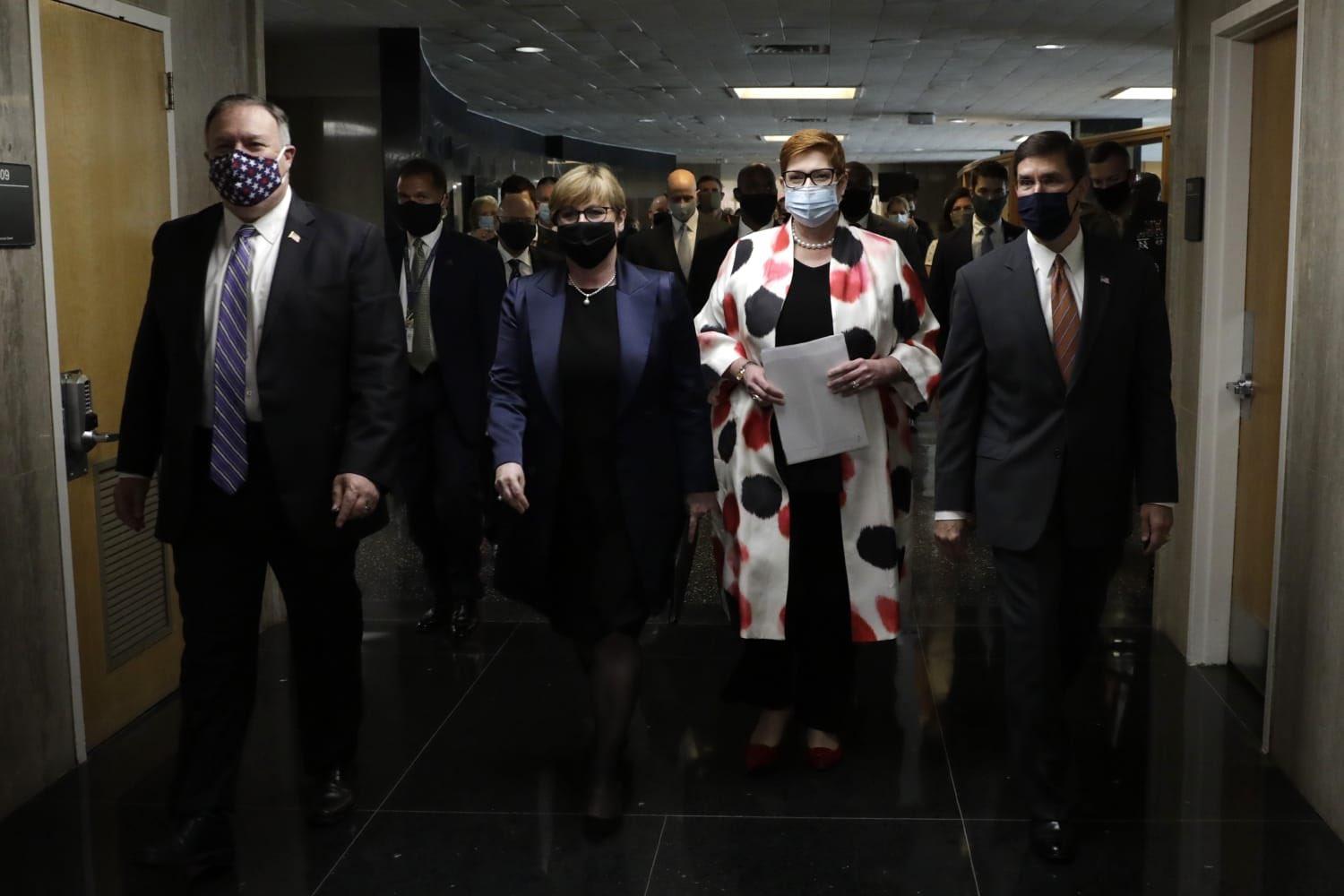

In 2018, our foreign minister challenged Moscow over Russia’s involvement in the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17. This year, Australia has led the international push for an independent investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic. Australia was taken seriously in these instances not because of the size or capability of our defence force, but because of the efforts and influence of our diplomatic corps.

While investing in power projection throughout the Indo-Pacific, the government must also invest in other tools of long-term influence, such as Australia’s development assistance budget, a line item long neglected, despite its strategic usefulness for building relationships with our Pacific neighbours and pushing back against the increasing financial leverage of states that do not share our values or strategic interests.

Increased expenditure on defence capability and acquisition is a positive step in the right direction for defence policy, as is the government’s overall strategic shift in the update. However, any increase in defence spending must be matched by increased funding for diplomatic efforts, including development assistance.

Policy announcements that continue to favour defence over diplomacy do not play to our strategic strengths. Without comparable attention paid to diplomacy, Australia will be left with some degree of military strength, but a reduced ability to build and maintain key partnerships in a region that we cannot win over with our relatively limited military might.

If we want to shape our strategic environment and deter aggression without a ‘great and powerful’ friend at our back, it will be through careful diplomacy and multilateralism, not through force of arms alone.