Semiconductors are the single most important technology underpinning leading-edge industries. They’re essential for the proper functioning of everything from smartphones to nuclear submarines and from medical equipment to wireless communications.

Australia’s notable lack of participation in the global semiconductor ecosystem has put it at a geopolitical disadvantage. As a nation, with some niche exceptions, it’s almost entirely dependent on foreign-controlled microchip technology, making it increasingly vulnerable to global supply-chain shortages, shutdowns and disruptions. Such occurrences have become all too common, either because of events such as the Covid-19 pandemic or because of other governments’ attempts to weaponise supply chains for geopolitical reasons.

Having unfettered access to microchips is a matter of economic and national security, and, more generally, of Australia’s day-to-day wellbeing as a nation. In an increasingly digitised world, policymakers must treat semiconductors as a vital public good, almost on par with basic necessities such as food and water supplies and reliable electricity.

By some calculations, Taiwan manufactures 60% of the world’s semiconductors and 90% of the most advanced chips. That alone should focus our minds on how we might shore up our future supplies of this critical resource.

The best solution is for Australia to build its own semiconductor manufacturing capability in selected areas matched to its research and development strengths and key markets. To do otherwise will expose Australia to significant risk, severely constrain our growth as a technological nation and consign us to second-tier status.

Granted, it would be an enormous undertaking—as many well-informed observers including Chief Scientist Cathy Foley have stated. Indeed, we call it a ‘moonshot’ in a report we are releasing today through ASPI.

However, there is a viable pathway that includes pursuing public–private partnerships from an existing R&D foothold, embedding Australian enterprises in friendly and reliable value chains, attracting talent and investment, and leveraging our relationships with strategically aligned and technologically advanced partners. Our report sets out the global context and key elements towards a national semiconductor plan, in which a $1.5 billion government investment through a combination of grants, subsidies and tax offsets could mobilise $5 billion in manufacturing activity.

Other like-minded nations have recognised the urgency and are moving quickly.

The United States and the European Union have both introduced ‘CHIPS’ Acts this year, which deliver subsidies for semiconductor sectors and support for areas that depend on advanced chips, such as 5G wireless, artificial intelligence and quantum science. Japan, South Korea, India and China are all stepping up their efforts. There is a race on, and Australia needs to move decisively.

The fact is, we are no longer in a period of economic liberalism and unrestricted free trade. Rather, nations have found it necessary to adopt the practice of ‘managed trade’ with a pragmatic techno-nationalism. This has been driven by geopolitics, most obviously by China’s mercantilist approach, but also by factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change, which is encouraging shorter supply chains in efforts to decarbonise economies.

Australia has some important strengths: strong institutions, a network of universities and R&D bases, an enterprising business sector, and good friendships with other leading technological nations with whom we share strategic interests, such as the US, the UK, Japan and South Korea. We need to use deft tech diplomacy and get ourselves into global value chains that are made up of reliable, strategically aligned countries—so-called friend-shoring.

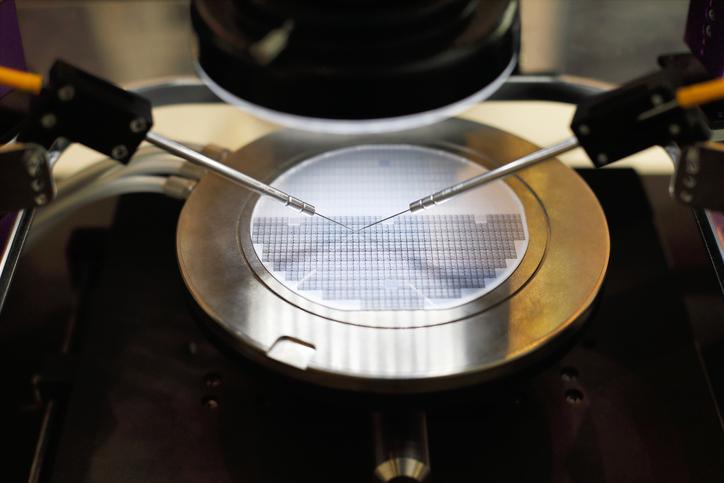

Australia already has an important R&D base upon which it can build its new capabilities, in the form of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) network under the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Scheme, which with a modest investment could become more commercially relevant and attract and anchor real commercial foundries.

The ANFF, with eight nodes across Australia, enables researchers to innovate and fabricate advanced products including semiconductors, but not currently at any scale beyond research. Doubling the cumulative investment in the ANFF with a further $400 million in catalyst funding would enable selective key nodes to escalate from one-off R&D to develop pilot production lines geared to volume and yield, closing the gap to producing chips commercially.

They could then create a pipeline of talent and form commercial partnerships. Companies that see this activity are more likely to invest in Australia because they can locate a foundry close to one of these key nodes, rather than build from scratch. Several national and international examples are outlined in our ASPI report.

Significant subsidies and tax concessions would attract semiconductor firms to invest here as part of public–private partnerships. The arrangements set out in the US CHIPS and FABS Acts are a good guide and could be scaled to Australia’s comparative stage of development. Such a commercial foundry partnership would be in the order of a $2 billion investment at a tailored entry point.

The ANFF network already has strength in the research-scale fabrication of compound semiconductors, which use two or more elements and are important in areas such as 5G, photonics and electric vehicles, and we should sensibly start there.

We can then work towards establishing a commercial silicon complementary metal-oxide semiconductor foundry, initially at mature process scale for which there are important markets, and over the longer term, progress to develop leading-edge chips requiring more investment.

We need to ensure that a local talent and innovation pipeline reinforces Australia-based commercial foundries by working with Australian universities and government R&D agencies, and via semiconductor-oriented degree and technical qualifications from universities and technical colleges. We should work with other trusted nations to strengthen this talent pipeline through coordinated research and training among key research universities.

We believe the plan we are putting forward, outlined in detail in the ASPI report, constitutes an implementable blueprint for Australia, not just a pie-in-the-sky idea. Nobody thinks it will be easy, but the strategic imperative is clear.

There are sceptics who will argue we are too small, and that our near-absent commercial chip fabrication capacity means we should concentrate instead on chip design and leave manufacturing to others.

That might be fine in a perfect, rules-based world, but in the real world of supply-chain uncertainty and darkening strategic horizons, we have to address this centre of gravity to avoid being forever a bit player, totally reliant on foreign chips.