As 2023 draws to a close, how should we assess progress on the government’s stated objective of ‘stabilisation’ in Australia–China relations?

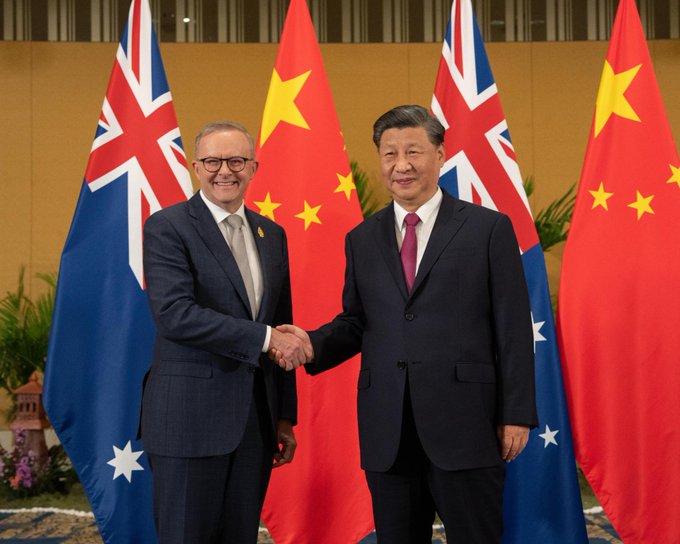

On the face of it, the Australian government has built significant momentum this year towards restoring relations with China to an even keel. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit to Beijing, in early November, was the obvious high point, signalling a diplomatic thaw after a years-long freeze.

We’ve seen the release of Australian journalist Cheng Lei and the prospect of senior Chinese government officials visiting Australia in 2024. And the government can point to some success in the area in which it has put the most focus—securing the winding back of punitive trade barriers Beijing imposed against a range of Australian imports from mid-2020.

Stability is, of course, a laudable aim in the abstract. However, it is becoming increasing clear that the diplomatic rhetoric of stabilisation is wearing very thin (and in fact risks being distracting or self-delusory) when the underlying reality is so at odds—namely, Beijing’s ongoing destabilising behaviour and the fundamental differences in our strategic interests and political systems.

First and foremost, though least obvious, it encourages a damaging relationship-management mindset towards China. This is a common foreign policy trap that Beijing knows how to play to its advantage. Whenever China succeeds in elevating subjectively defined atmospherics as a basis for engagement, it undermines national-interest considerations if the other side accepts that differences should be minimised in order to establish goodwill or to maintain access.

Canberra needs to be careful not to overemphasise a relationship-building approach towards China, especially one centred on personal diplomacy between Albanese and Xi Jinping. In China, the PM said he regarded Xi as an ‘honest and straightforward’ interlocutor. Earlier, he said Xi ‘has never said anything to me that he has not done’. While Albanese may have made such comments in the context and spirit of relationship building, such descriptions are a shaky foundation for a substantive relationship.

The most obvious weakness with ‘stabilisation’ is that it runs directly counter to China’s deliberately destabilising behaviour in the East China Sea, Taiwan Strait and South China Sea and across its land borders with India and Bhutan. This has continued unabated since Labor came to power. In particular, the unsafe and unprofessional use of sonar by a Chinese warship, injuring Australian divers from HMAS Toowoomba right after the PM’s visit to China, dramatically undercut Canberra’s claim to have steadied bilateral relations. This incident forced an immediate course correction from the government, when Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles condemned China’s ‘aggressive’ behaviour, in a media interview in India.

Beyond scripted joint statements issued at international summits, Australia’s ministerial line-up has appeared reluctant to call out China’s escalatory and intimidating behaviour towards the Philippines in recent months. Official statements of concern have seemingly been pushed down to the ambassadorial level.

Labelling Beijing’s actions as destabilising has arguably become harder for the government now that it has made ‘stabilisation’ the main metric of its China policy. That said, the most recent statement issued by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in support of the Philippines marks a noticeable strengthening in our language, though it also highlights the limitations if not contradictions in the government’s stabilisation narrative. It is also abundantly clear that Australia continues to compete geopolitically and directly with China in the South Pacific and that this is driving Canberra’s statecraft in the subregion.

As I wrote in Australia’s security in China’s shadow, the paradigm undergirding the Australia–China relationship swung from economics to geopolitics around a decade ago and won’t swing back again quickly. A competitive, largely adversarial framing is more likely to define the future than one based on expanding cooperation.

Even in the economic arena, where the government’s diplomatic efforts have borne the most tangible fruit, stabilisation is falling short of Canberra’s expectations. Trade Minister Don Farrell has said he is ‘very confident’ that ‘by Christmas’ China will remove all remaining trade impediments against Australia, predicting that ‘we will have restored that stable relationship that we want with our largest trading partner’.

In fact, China is likely to defy Farrell’s optimism by keeping a range of trade restrictions in place. This is Beijing’s best tactic to ensure that Australia remains absorbed in the ‘low politics’ of bilateral trade, averse to the risks of spillover from more contentious policy differences. Businesses desperate to re-enter the Chinese market are likely to counsel caution against holding Beijing to account in their own cause of stabilisation, narrowly defined. China’s efforts to coerce Australia, including through economic means, haven’t ended—they are merely likely to take on new and more pernicious forms.

The other shortcoming of the stabilisation narrative is that it underplays the fact that the primary explanation for China’s fence-mending approach towards Canberra wasn’t Labor’s superior diplomacy in comparison with the previous Coalition government, but Beijing’s own realisation that its efforts to coerce Canberra into a more compliant mindset had failed.

While certain export industries have undeniably suffered as a result of China’s economic punishment campaign, Australia avoided macroeconomic damage because of the success of market diversification efforts, by both government and the business sector. In fact, the value of bilateral trade with China scaled new heights, because China continued to import the commodities it most needed from Australia, at prices inflated partly by its own politically motivated interference.

The most important revelation from China’s attempts to punish Australia economically was Australia’s underlying resilience as a competitive exporter in a global, rules-based trading system. In the final analysis, Australia’s macroeconomic stability was shown not to depend on the political health of its relationship with China.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong has recently transitioned to talking about Australia–China relations in terms of a need to ‘navigate our differences wisely’. As 2024 beckons, with all of its uncertainties, perhaps it’s time to quietly retire ‘stabilisation’ as a narrative that has served its limited purpose.