When Peter Wright remarked: ‘That will fix the bastards’, while leaving the NSW Supreme Court witness box on 8 December 1986, he was firing a salvo in the ‘Spycatcher affair’, a political and legal controversy that is remembered as a defiant win for transparency over secrecy. But the actual lesson of Spycatcher is that not all revelations about intelligence matters should be considered uncritically.

A former senior technical adviser with British security service MI5 turned struggling Tasmanian horse breeder, Wright and co-author Paul Greengrass had written an expose of British intelligence, Spycatcher, only to have Her Majesty’s government seek the book’s banning in Australia, as in England.

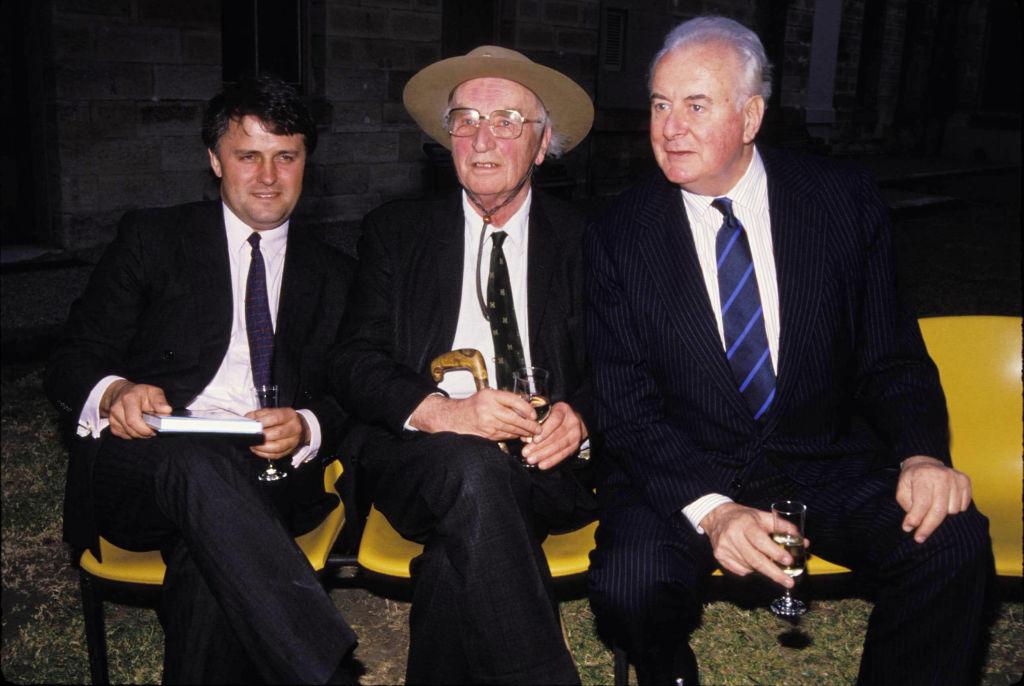

The resulting trial was disastrous for Margaret Thatcher. Her cabinet secretary, Robert Armstrong, was humiliated by future Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, representing the defendants. The Court found for Wright’s publishers, as would Australia’s High Court on appeal, albeit on a technicality.

Spycatcher could be sold in Australia, and eventually in England. Legal controversy (‘the shocking book of secrets Britain banned’) made it a bestseller and Wright a millionaire. Not bad given that Turnbull’s principal legal defence had been that it was a regurgitation of old news.

To this day Spycatcher remains a watchword for transparency triumphing over bloody-minded secrecy; a victory over bureaucrats being ‘economical with the truth’. According to Turnbull, ‘We struck a blow for democracy and transparency and openness. And that was a good thing’.

Battles over the release of Spycatcher-related government records continue to the present. Journalist Tim Tate’s just-published book, To catch a spy, unearths insights into the Thatcher government’s legal and political strategy, and confirmed that Armstrong committed perjury.

However, Spycatcher also serves as a reminder of the importance of scepticism and balance when evaluating claims of undue secrecy.

For there was an all-consuming reason Wright wanted the ‘bastards’ to pay: the conviction that his former boss Roger Hollis—MI5 director-general 1956-65 and contributor to ASIO’s establishment—was a Soviet mole (the ‘Fifth Man’), whose treason led to failed British counterintelligence efforts against the KGB and GRU (Soviet military intelligence). Or, according to Wright at other times, it was Hollis’ deputy Graham Mitchell who was the mole.

This was not merely a passing assertion in Spycatcher; it was the narrative throughline, principal motivation—along with filthy lucre—and the most alarming allegation made.

The allegation had been dismissed within MI5’s own ranks by the time it was raised publicly by journalist Chapman Pincher in the early 1980s; this was a majority view before Wright’s retirement in 1976. Younger staff joked about Wright being a KGB illegal sent to disrupt and confound Western counterintelligence.

Wright’s theory was undermined by anti-Soviet success during Hollis’ tenure, namely the Portland spy ring’s uncovering. But Wright’s own flexible logic was that this simply proved his point, as the Soviets would only be willing to sacrifice their operations for such a valuable penetration.

British civil servant Lord Trend, reviewing the matter independently in 1974–75, found no conclusive evidence of Hollis’ guilt. Given the impossibility of proving a negative, Trend estimated, based on the circumstantial evidence, that the possibility of Hollis being a spy was roughly 20 percent.

Some still question Hollis’ innocence. Like Wright, Pincher went to his grave convinced he was right. Tim Tate is sympathetic to Wright’s case against Hollis, albeit his book offers little new information on the Hollis question. Australian intelligence commentator Paul Monk has made his own detailed case for Hollis being ELLI, the GRU source alleged to be inside British intelligence during World War II. Some studies are ambiguous, while others assess the case for Hollis as ELLI to be weak.

Today MI5 dismisses the notion of Hollis’ guilt outright. Christopher Andrew’s official history was scathing: ‘no credible evidence since there was none to find’, ‘threadbare’, ‘a form of paranoia’. Internal MI5 reviews (including post-Spycatcher) were damning of Wright, accusing him of fabrication and distortion. KGB defector Oleg Gordievsky claims the Soviets were so confused by the public allegations that they assumed it was some kind of inscrutable double-bluff. No evidence of Hollis’ guilt emerged from the brief post-Soviet archival openings, or Vasili Mitrokhin’s haul from the KGB. The actual ‘Fifth Man’—John Cairncross—had been identified and confessed in 1964. Excepting Wright’s confidant James J. Angleton, the CIA’s leadership didn’t believe Hollis was a mole and a 1993 CIA study of related literature (including Spycatcher) labelled the charges against Hollis and Mitchell as ‘false’.

Thus, Spycatcher presents an uneasy lesson. For all Wright was correct about, especially that a significant number of Britain’s elite committed treason during the 1930s and 1940s without consequence, he was obsessively wrong in his central thesis. But his whistleblowing spread that thesis, propelled by Thatcher’s quixotic legal strategy (and duplicitous political strategy) and the media’s credulity.

Nonetheless, Spycatcher had positive, if inadvertent, outcomes.

Ironically, Thatcher had herself raised public expectations of transparency about the intelligence services. She made a parliamentary statement in 1979 confirming Anthony Blunt’s (‘the Fourth Man’) confessed Soviet spying. Although the terms in which she did so helped rouse Wright from retirement.

Moreover, Armstrong had been compelled to insist openly that he could neither confirm nor deny that Britain’s foreign intelligence service MI6 actually existed. However, he could acknowledge that it existed between 1956 and 1968 when headed by Dick White. The derision with which this insistence was met would be a contributing factor to the acknowledgement of MI6 through the Intelligence Services Act in 1994, and a Security Service Act for MI5 in 1989.

Spycatcher prompted introduction of an ombudsman function within Britain’s intelligence services, as well as processes for dealing with intelligence officers’ memoirs.

There has also been broader recognition, including in Australia, that secrecy remains a fundamental enabler of national security—if justified and justifiable. And that purposeful transparency, such as public statements and official histories, can actually serve the national security mission.

Spycatcher doesn’t repudiate the case for appropriate disclosure and transparency in intelligence and security. But we should all be discerning, even sceptical, when secrecy is assailed in the public square. This includes reflection on the wide-ranging oversight, transparency and disclosure mechanisms actually in place in Australia.