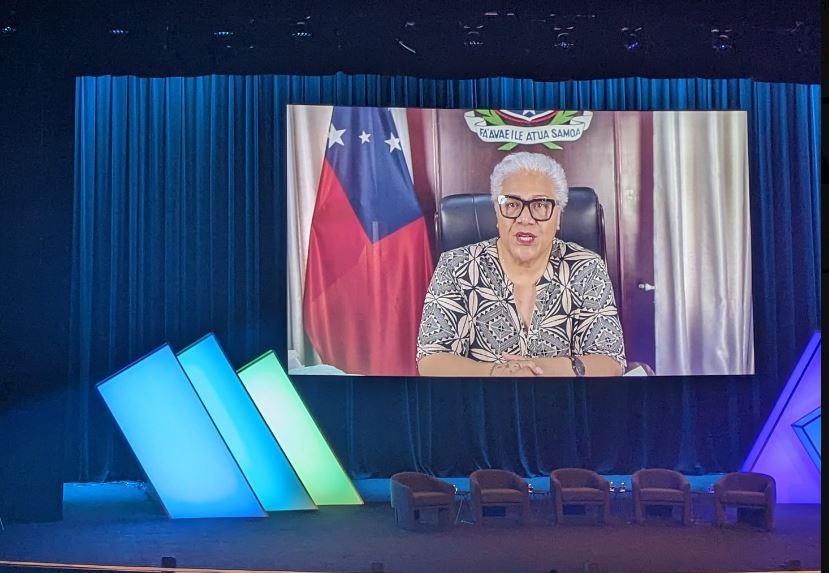

Samoa’s prime minister, Fiame Naomi Mata‘afa, gave the opening keynote address on Day 2 of ASPI’s Sydney Dialogue. An edited version of her speech follows.

Small island developing states are facing a range of challenges due to their size, isolation and vulnerability to external forces. These include rising sea levels, extreme weather events and economic instability. Additionally, small island states have limited resources for adaptation and resilience, limited access to global markets and capital, as well as recognising their specific IT challenges, from expanding access to affordable and reliable connectivity to promoting digital literacy.

Technology has the power to transform island states and bring about positive change. It can help reduce poverty, create jobs and improve access to health care, education and other essential services. It can also bridge the digital divide between rural and urban areas by providing internet access. With the right technology in place, we can become more resilient to climate change and natural disasters. By harnessing the power of technology, island states can become more self-sufficient and maximise their potential for growth.

With the help of innovative solutions, small island developing states can make strides towards reaching their development goals. From renewable energy sources to ‘smart city’ technologies and digital infrastructure, there are a number of ways that islands can leverage technology to increase efficiency and sustainability. By exploring these solutions and investing in the right ones for their needs, islands can ensure that they have the resources necessary to achieve their development goals.

Small states face a lot of challenges in terms of economic opportunities and development. One way to tackle these issues is by developing digital skills that can be used to enhance the economic opportunities for people living in small islands. Through digital skills, people can access new markets, develop innovative products and services, generate jobs [and] be more competitive in the global market.

Data sciences and artificial intelligence can help small island communities gain access to real-time information on climate change, natural disasters and other environmental issues that threaten their livelihoods. This data can be used to inform decision-making processes related to conservation efforts, renewable energy projects and other initiatives that promote sustainability in the long term, as well as enable forecasting to anticipate future trends and potential risks. Leveraging technology in an effective manner means we have access to the resources we need to create a brighter future for ourselves.

Right now, the International Telecommunications Union is rolling out an initiative in the Pacific that will help deliver digital services in education, agriculture and health in support of recovery through the ‘smart islands’ project to boost digital transformation in the hardest-to-connect communities. The approach here relies on multistakeholder collaboration to create an equal digital future.

The challenges for small island states are not only about small domestic markets and small numbers of ICT suppliers. Often people do not know how to take advantage of the technologies. There is often a lack of awareness of the advantages of connecting, a lack of relevant local content online in the local language and a much higher cost of connection than in most countries. Many small island states states rely on satellite connections, and a small domestic market does not offer industry enough return on investment—nothing like the large urban areas. Industry therefore needs to be incentivised; regulatory frameworks need to be harmonised. Regional cooperation is key to creating a larger community with harmonised regimes, including spectrum management and incentives to encourage investment.

Reliable, fast, affordable international connectivity opens up huge potential for small island states. We have seen this in the Pacific once a cable was landed. Cost-based tariffs provide a guiding principle, coupled with universal access, to ensure that no one is left behind. For this to happen, states and their partners must encourage greater collaboration and cooperation, with each of us bringing specific competencies to the table, if the objective of achieving universal, equitable and affordable access to ICTs is to be achieved.

While it is not a new area of technology, there is no doubt today that continuous advances in network computing and other aspects of ICT are converging with advances in other technological fields, greatly increasing human dependence on these digital tools. Governments around the world are establishing new institutions, identifying the policy implications of this growing digital dependence, and developing integrated frameworks for whole-of-government approaches to manage the resulting economic and societal transformations. As a small island state, Samoa is struggling to develop such an integrated framework.

Despite the associated benefits, humanity’s growing dependency on ICT continues to present significant risks. Cybersecurity, and the stability of ICT systems more generally, have become top policy priorities. Globally significant technological advances are being made across a range of fields, including ICT, artificial intelligence, particularly in terms of machine learning and robotics, and space technology, to name but a few. These breakthroughs are expected to bring about major transformative shifts in how societies function.

We do have concerns that these technologies and how they are used will pose serious challenges, including labour force dislocations and other market disruptions, exacerbated inequalities, and new risks to public safety and national security.

These technologies are mostly dual use, in that they can be used as much to serve malicious purposes as they can be harnessed to enhance social and economic development, rendering efforts to manage them much more complex. Given the relative ease to access and use of such technologies, most of them are inherently vulnerable to exploitation and disruption. In parallel, geopolitical tensions around the world are growing, and most countries increasingly view these technologies as central to national security.

The potential for misuse is significant because of greater economic integration and connectivity. This means that the effects and the consequences of technological advances are far less localised than before and are liable to spread beyond borders. Technological innovation is largely taking place beyond the purview of governments. In many cases, the rate of innovation is outpacing states’ ability to keep abreast of the latest developments and their potential societal impacts.

Devising policies for managing these effects is a complex process given the number of players involved, the different values and political systems at play, and the cross-border reach of the technologies. This is particularly the case when technologies are designed for profitmaking alone and their trajectories are entirely dependent on the market.

A case in mind is cyberspace, where there are new risks and vulnerabilities. Responding to the attendant risks and challenges will not require just exploring new governance structures, tools and processes. It calls for a deeper understanding of the social, cultural, economic and geopolitical context in which policy norms and regulations are crafted, as well as a firmer grasp of the overarching questions of power and conflict that shape humanity’s relationships with technology.

Moreover, significant public engagement is critical. There is a need to ensure that the values of equity, equality, inclusivity, responsibility, transparency and accountability that might be negatively impacted by certain technological advances are given consideration and how those values might best be protected. There is a need to enhance transparency, oversight and accountability. New policy and regulatory approaches will require greater investment in transparency, oversight and accountability mechanisms.

This will necessitate agreeing on the nature of national regulatory oversight bodies and determining whether they should be public, private or of a mixed composition. Growing strategic competition between the world’s leading powers, especially in high-tech sectors, will not be conducive for multilateral efforts to respond cooperatively and effectively and may lead to a delay to the much-needed normative and regulatory action. This potential impasse places strains on existing efforts and could further delay the attainment of social and economic objectives, such as the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals, which are already under stress.