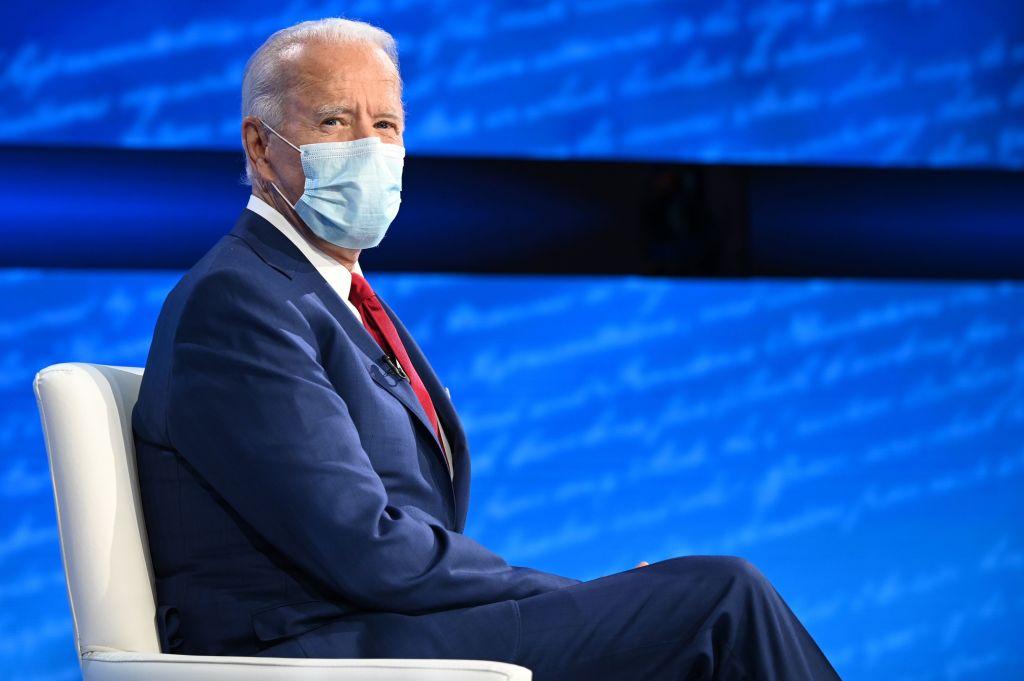

Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential election has been met with a wave of relief across Europe, where many feared that a second term for Donald Trump would have threatened the very survival of the European Union. Biden offers at least the prospect of restoring a more traditional transatlantic relationship. Many assume that the United States will return to leading the liberal international order, with Europeans playing a supporting role through diplomacy and soft power. Batman and Robin are back.

But this vision is a mirage. Long before Trump and his ‘America first’ doctrine, a series of crises—the Iraq War debacle, the global recession—had sapped the US’s willingness to continue serving as the world’s policeman. And over the past four years, other powers—China, Russia, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and many others—have been filling the vacuum created by America’s inward turn. Much of the global governance architecture has been hijacked by China and other powers and is now buckling under the weight of great-power competition.

Despite these geopolitical developments, some European Atlanticists have been hesitant to pursue greater self-reliance for fear of offending the US, whereas others secretly wished for a Trump victory on the grounds that it would finally shake Europe (especially Germany) from its complacency. Those in this second camp believe that Europe has made more progress towards securing its own sovereignty over the past four years than it did under the presidencies of Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton combined.

In this sense, Trump—an exponent of everything Europeans oppose—may have served as the accidental father of European sovereignty. The politicians most supportive of a strong transatlantic alliance find themselves paradoxically tolerating outcomes that could well destroy it.

Concerned with maintaining its global strategic primacy, the US was once ambivalent about European defence and strategic autonomy. But as power has shifted eastward, subsequent US governments have been keen to devote as much attention, money and military muscle as possible to the Indo-Pacific. The last thing the US wants is to get sucked into more ‘forever wars’ in the Middle East or political conflagrations in Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

Accordingly, US strategic planners today do not object to a stronger, self-reliant Europe, but a weak one that diverts scarce US resources from the rivalry with China. The US is looking for a partner, not a collection of needy children who take no responsibility for their own welfare. The Biden administration will want to work with a Europe that offers solutions, not more problems.

Atlanticists who take the long view realise that the critical task now is not to restore the transatlantic relationship but to transform it. An EU that achieves strategic autonomy might not always agree with the US on issues such as data privacy, energy policy or even global trade. But it would manage these differences pragmatically, while always standing shoulder to shoulder with America on the values-based issues that count. Instead of waiting for cues from the next American president, Europeans should already know what the US expects and be prepared to meet it halfway.

On China and the issues surrounding 5G, for example, Europeans don’t need to wait for instructions from the US: they should already be preparing the ground for something like a comprehensive transpacific–transatlantic partnership. New arrangements are needed to circumvent Chinese resistance to substantive reforms to the international trading architecture, and to pressure China to curb its market-distorting practices.

Likewise, on Russia, Europeans should already be devising a new Eastern partnership to bring both European and US security assistance to the frontlines of the struggle. On climate change, Europe needs to move quickly to develop an EU–US carbon border adjustment mechanism, and to invest more in a green-tech alliance to boost economic competitiveness. And on Iran, Europeans can anticipate renewed negotiations on a revamped nuclear deal aimed at de-escalating tensions across the region.

From the US perspective, the biggest threat to Atlanticism is not European sovereignty, but rather European dependence. Trump has spent the past four years pulling at the strings of Europe’s internal divisions. If Biden wants to reinvent American leadership for the 21st century, he will need to push Europe to become self-reliant.

Biden has promised Americans that he will pursue unity and bring an end to a ‘grim era of demonization’. He could do the same for Europe, and without any costs to American taxpayers, by bringing new pressure to bear on the countries that are undermining European unity from within—namely Poland and Hungary. From day one, Biden should make clear to these countries’ governments that the road to the White House runs through Brussels. That would already make him a better advocate for European sovereignty than Trump was, and it would represent a big step towards implementing a new American grand strategy.

There is a strong parallel between this approach and the debates about Covid-19. The top post-pandemic priority is not to ‘reconstruct’ the status quo ante, but rather to use the crisis as an opportunity to fix the things we already knew were broken.