Australia invites itself to America’s wars—Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. A singular purpose runs through them all: the US alliance.

Australia invites itself so it can pay its alliance dues. It’s the insurance model Prime Minister Robert Menzies explicitly invoked in going into Vietnam. Paying the alliance insurance premium explains much about Australia’s long war in Afghanistan and our role in the Iraq blunder-cum-nightmare.

The self-invitation process can be swift and built on high emotion, as it was when South Korea was invaded (Australia’s quick response helped clinch the ANZUS alliance) and in Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks.

The 1991 Gulf War sits close to this category, but doesn’t fit my ‘America’s wars’ typology. The key motive for Australia’s involvement was to support the UN and international law by overturning the Kuwait invasion. With the US alliance as a secondary driver in 1991, Australia’s contribution was primarily naval; no boots on the sand and no Australians in combat.

Other times, as in Vietnam and Iraq, a step-by-step journey builds slowly until it culminates in Australia’s commitment to the conflict. This is not sleep-walking to war. Many debates and decisions are involved. But a sense of narrowing options, even inevitability, can grip Canberra. A literary version of how this feels is offered by Ernest Hemingway:

How did you go bankrupt?

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.

A key starting point for the self-invitation to the Iraq war in 2003 is detailed in the Howard government cabinet records for 1998 and 1999, just released by the National Archives of Australia.

More than five years before the Iraq war, Australia lined up and signed on. And in an important contrast with Vietnam, in Iraq we integrated ourselves into US military planning.

At the start of 1998, Baghdad suspended cooperation with the UN weapons inspection regime on Iraq’s biological, chemical and missile capabilities. The US and Britain threatened Iraq with military retaliation and began to build up forces in the Persian Gulf.

Early in February 1998, Howard briefed cabinet on his discussions with US President Bill Clinton and the prime ministers of Canada and New Zealand on Iraq and on ‘recent decisions’ taken by cabinet’s National Security Committee.

Cabinet affirmed the committee’s decision to ‘offer military support to the United States’ coalition’—special forces personnel, two air-to-air refuelling aircraft, and medical and intelligence specialists. Cabinet granted the committee ‘authority to agree to support of a similar magnitude … if the support proposed cannot be incorporated into US plans’.

On 20 February 1998, cabinet approved two sets of rules of engagement, ‘a defensive ROE applying during peacetime and the second, if necessary, an operational ROE for use during conflict’. Both sets of rules provided for integration into a coalition force, with the operational ROE placing the Australian Defence Force under the ‘direction of the coalition force commander, with ADF elements to remain under national command’.

The rush to war reversed as the UN secretary-general swung into action and Iraq stepped back.

By March, the National Security Committee noted Iraq’s ‘current cooperative approach’ and the failure of fresh inspections to find evidence of weapons of mass destruction. Iraq was likely ‘to place pressure on the UN Security Council to lift sanctions’. The committee further noted that the US intended to maintain its military deployment until at least September.

In May 1998, cabinet considered its options for Australian military support for operations in the Gulf. The starting point was that the US should maintain its commitment to the military coalition, plus continuing support from Kuwait.

ADF liaison officers should be integrated into the US land headquarters in Kuwait, the special forces headquarters in Kuwait, the air operations headquarters in Saudi Arabia and the US Central Command in Florida.

The alliance insurance method is served by military integration. Yet integration can define and drive commitment.

Australia did a better job of military preparation for Iraq than we did for Vietnam. Australian officers were embedded in the US system and took part in a prolonged period of military planning for the Iraq invasion. In Vietnam, by contrast, where Australia’s first battalion was deployed was decided by the US and advised through diplomatic channels.

Australia went into Iraq far more cautiously and got out as the dust of invasion cleared. We were slowly drawn back in by alliance demands in later years, but again the commitment was limited, which is why the price paid in Australian blood was so low. No Australian soldiers died during the invasion.

What we did in Iraq was very much about the US and very little about Iraq. Canberra even quibbled about its responsibility for Iraq’s future as one of the occupying powers, insisting that was a question for Washington.

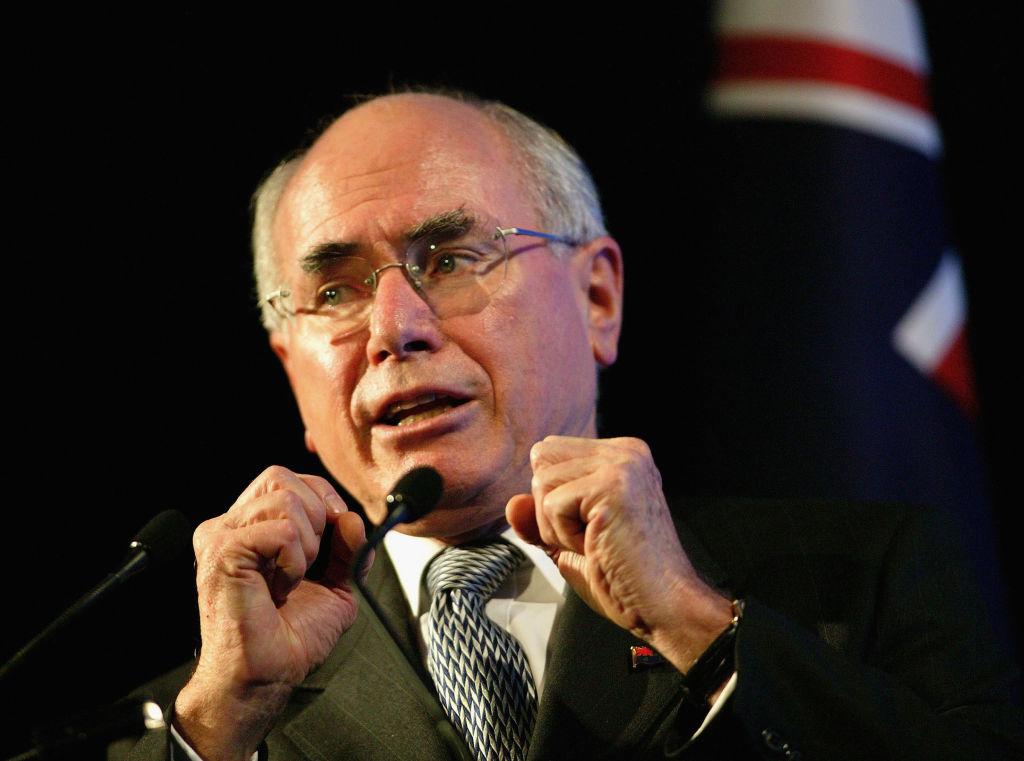

Australia’s decision in early in 1998 set the conditions for what I’ve called John Howard’s ‘fib’ about invading Iraq in 2003.

The fib was that Australia still had an open mind on going to war. The prime minister’s fib was that Australia was weighing all the options and didn’t commit to the invasion until the final moment.

Note the use of the word ‘fib’ instead of ‘lie’. This is a political distinction, not to be tried when disciplining children or giving evidence under oath. The fib in its political garb is designed to conceal or avoid the whole truth. There’s a bit of truth within the fib, but the assertion isn’t wholly true.

Howard’s brisk chapter on Iraq in his autobiography makes explicit the lack of any question, or much debate, about Australia joining the US war.

The book recounts the White House talks in June 2002, where George W. Bush understood that Howard ‘would keep [his] options open until the time when a final decision was needed’. But the ‘tenor’ of Howard’s comments to Bush meant the US knew it could rely on Australia.

Beyond self-invitation, integration builds a detailed involvement that delivers what seems the inevitable commitment to pay the insurance premium.