Last week, the US Department of Justice unsealed a significant criminal complaint. Police officers from China’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS) were charged with creating ‘thousands of fake online personas on social media sites, including Twitter, to target Chinese dissidents through online harassment and threats’ and for spreading ‘propaganda whose sole purpose is to sow divisions within the United States’.

This announcement marked the first definitive public attribution to a specific Chinese government agency of covert malign activities on social media. However, the MPS is one of many party-controlled organisations that analysts have long suspected of conducting covert and coercive operations to influence users on social media.

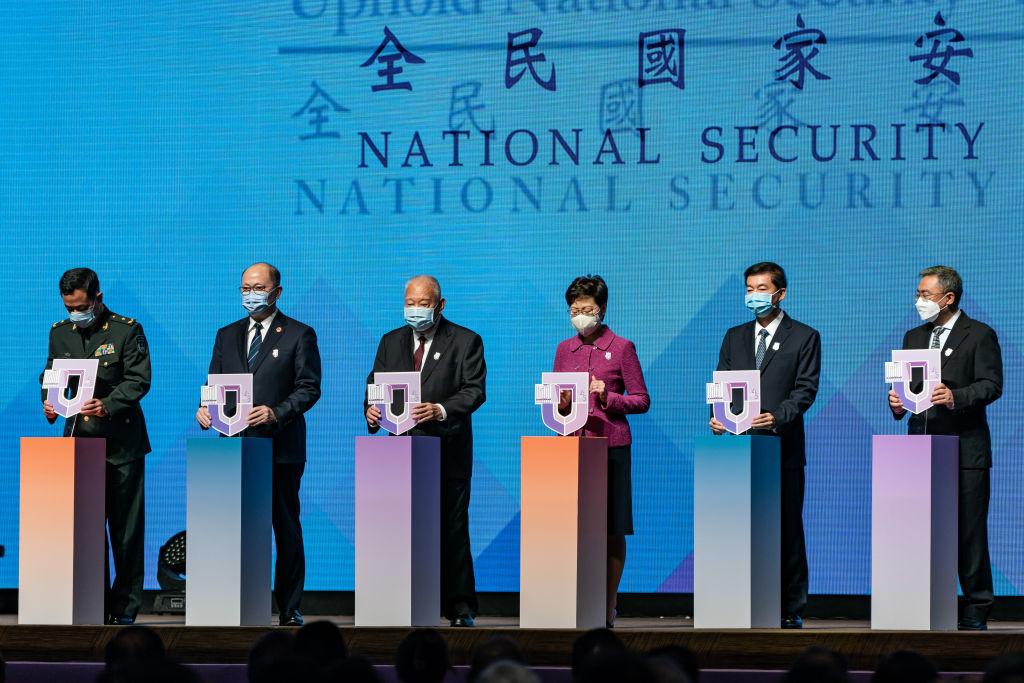

Under the guise of ‘guiding public opinion’, a policy concept that dates back to the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) justifies its manipulation of information to maintain social stability and political control over China. More recently, China’s authoritarian leader, Xi Jinping, has revived the Cultural Revolution-era term ‘public opinion struggle’ and declared social media ‘the main battlefield’ because of its ability to spread values and ideas—like human rights and democracy—that are perceived as threats to the party’s political legitimacy.

The CCP’s efforts to shape public opinion online now go beyond simply censoring dissidents and spreading pro-government propaganda. They are more global and aggressive, often directly interfering in state sovereignty and democratic discourse and supporting the party’s broader strategic and economic goals.

ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre has published a new report entitled ‘Gaming public opinion: The CCP’s increasingly sophisticated cyber-enabled influence operations’, alongside reporting by The Washington Post which explores the growing challenge of CCP cyber-enabled influence operations conducted within democracies through social media.

The report canvasses the existing publicly available evidence of covert cyber-enabled influence operations originating from China to provide an assessment of the CCP’s evolving capabilities. We find that the CCP has developed a persistent capability to sustain coordinated networks of personas and that multiple Chinese government agencies probably conduct, in parallel if not collectively, covert influence operations on social media. Those operations have become more frequent, sophisticated, and effective in targeting democracies by disrupting domestic and foreign policies and decision-making processes.

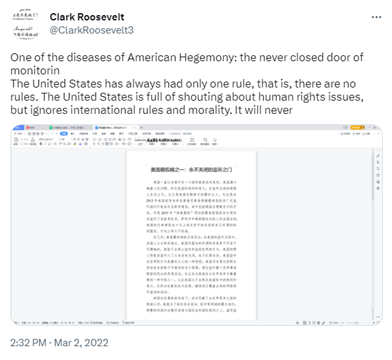

As a case study, we reveal a previously unreported CCP cyber-enabled influence operation linked to the Spamouflage network, which Twitter and Meta attributed to the Chinese Government in 2019. This new iteration of the network is using inauthentic accounts on US-based and China-based social media platforms to spread unverified claims that the US is irresponsibly conducting cyber-espionage operations against China and other countries. Drawing on slip-ups like an open browser tab identifiable in an image accidentally tweeted by a Spamouflage-linked account, we believe the Chinese Government agencies conducting this influence operation named it ‘Operation Honey Badger.’

Those anti-US claims appear to be part of a broader CCP propaganda campaign to support the expansion of Chinese cybersecurity services abroad and counter similar accusations of Chinese cyber operations. There may also be a domestic propaganda purpose to garner public support for China’s new cybersecurity laws by highlighting the US as a major threat.

Accounts in the network often posed as Westerners outside of China but our research geolocated some of the operators of the Spamouflage-linked accounts to Yancheng in Jiangsu Province. In addition, we show it’s likely that at least some operators behind the campaign are affiliated with the Yancheng Public Security Bureau, the MPS or are ‘internet commentators’ hired by the Cyberspace Administration of China.

The Washington Post discovered other possible links to Chinese police officers after ASPI shared a list of Weibo accounts that were likely part of the network. In one case, The Washington Post discovered an account that appears to have a self-taken photo of a Chinese police officer as its profile image.

Chinese cybersecurity company Qi An Xin (奇安信), a partly state-owned enterprise, also appears at times to be supporting the influence operation. Our research shows the company is deeply connected with Chinese intelligence, military and security services and that it might provide digital infrastructure support to Chinese Government agencies that conduct clandestine operations online.

Finally, the report provides key recommendations to policymakers and social-media platforms to counter the CCP’s increasingly sophisticated, cyber-enabled influence operations. Democratic governments and social-media platforms must shift from reactive responses to proactive strategies rapidly. This will require a reprioritisation of these issues and greater coordination and investment of resources.

For example, definitive public attribution like the unsealed US DOJ complaint can play a larger role in deterring malicious actors. The value of public attribution goes beyond deterrence too. It’s important that general publics are given basic information so that they’re informed about contemporary security challenges.

Social-media platforms should take advantage of the digital infrastructure, which they control, to more effectively deter cyber-enabled influence operations. To disrupt future influence operations, social-media platforms could remove access to engagement analytics for suspicious accounts breaching platform policies, making it difficult for identified malicious actors to measure the effectiveness of influence operations.

Government partners and allies should also strengthen intelligence diplomacy on this emerging security challenge and seek to share more intelligence with one another on such influence operations. Strong open-source intelligence skills and collection capabilities are a crucial part of investigating and attributing these operations, the low classification of which should make intelligence sharing easier.

For now, inauthentic accounts on social media—which hide their true origins and state affiliation—allow the CCP to continue pursuing its interests globally and provide plausibly deniable cover for its true strategic intentions. Those clandestine operations undermine the freedom of online users to form independent opinions and prevent general publics from judging and holding the CCP’s actions to account.

CCP influence operations have already had an immediate impact by silencing and deterring Asian women from reporting critically on China. Left unaddressed, the CCP’s increasing investment in influence operations online threatens to successfully influence the economic decision-making of democracies, destabilise social cohesion during times of crisis, sow distrust of leaders or institutions and processes, fracture alliances and partnerships, and further deter journalists, researchers and activists in democracies from expressing their opinions.