Sino-African relations have been of increasing interest to analysts since the turn of the century—in large part because the relationship is a measure of how the Chinese hope to use their burgeoning economic power in the world. Characterisations have ranged from ‘neo-imperialist’ peril to relatively benign investor. So which is it?

To the extent that China’s relationship with Zimbabwe is a microcosm, the answer is ‘neither’. It’s more complex than that.

The Chinese link with Zimbabwe’s ruling party, Zanu-PF, goes back to 1963—as does, notably, China’s association with new president Emmerson Mnangagwa. For the first decade and a half, the connection was military, with the Chinese providing training and materiel in the fight against white rule. Mnangagwa was part of the first group of guerrillas sent by Robert Mugabe to a military academy in Nanjing.

Yet the cynical and tactically agile Mugabe also ensured that independence in 1980 did not bring with it much reward for the Chinese. Speaking privately to a colleague (who happened to be a spy of apartheid South Africa), Mugabe described a celebratory state visit to China and North Korea as ‘a lot of bull’. It had been a necessary obligation, but the offer of aid by these allies was, in his view, just an attempt to establish a fifth column in Zimbabwe—a posse of ‘Marxists who will start a process of undermining’. If the relationship could be described as manipulative during the early years, it was Mugabe pulling the strings.

The balance shifted—or should have—after 2000 when Zanu-PF obliterated the white farming sector that was the bedrock of Zimbabwe’s economy. Mugabe’s ‘Look East’ policy—officially an attempt to circumvent Western sanctions, but in reality a beggar’s posture—was adopted just as the curve of China’s global trade graph began its precipitous turn to the north. On paper, the timing couldn’t have been better for the Chinese. But the results were dismal—mainly because the relationship was shot through with distrust and conflicting expectations, despite its longevity.

Much to the chagrin of China’s hard-headed post-Deng capitalists, the Zimbabweans proved unplayable much of the time. When they didn’t feel like it, the Zanu-PF comrades simply didn’t pay. A secret 2009 memorandum by Mugabe’s Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) noted that the Chinese were flummoxed by the corrupt fiddling of exchange rates that was de rigueur among Zimbabwe’s politically connected:

The Chinese have voiced their concerns over some projects, such as supply of tractors, which were treated as donations when they were, in fact, loans. At one point, there was a complaint about tractors being sold in Zimbabwe at a price lower than a bottle of mineral water. The Chinese were left wondering how Zimbabwe intended to repay the loan when such capital equipment was being distributed virtually for free.

Meanwhile, many Chinese ‘mega-deals’ were signed by Zimbabwean state-owned entities, but stuttered almost immediately because tight credit terms couldn’t be met amid the country’s economic anarchy—or never got off the ground because even the down payments were unattainable. The CIO commented that the ‘broader situation of Zimbabwe’s overdue obligations to China would provide an appreciation of how the Chinese perceive the country. This kind of information circulates extensively within Chinese circles.’

The CIO conceded that the Chinese naturally sought to ‘hedge their investments’ in such a climate, but also remarked that they appeared to regard Zimbabwe as ripe for the picking:

Chinese investors have been making incessant demands and seeking special dispensations outside Zimbabwe’s basic investment laws. Demands such as exemption from PAYE, VAT and Corporate Tax are exploitative given that no returns will be going to the State. Any reasonable investor should expect to pay some form of tax, in particular for finite resources such as minerals.

The Zanu–China relationship stumbled on in the years that followed, primarily for political reasons. For Harare, the Chinese were useful both internationally and domestically, providing a reliable veto against possible Western ‘machinations’ in the UN Security Council and rendering assistance on national security matters—namely, some of the intelligence and military capacity required to resist political change. For Beijing, Zimbabwe was an important symbol in Africa of China’s constancy as a friend—and there seem to have been hopes of a steadier partner at the helm of Zanu-PF once the troublesome and economically deranged ‘old man’ had gone.

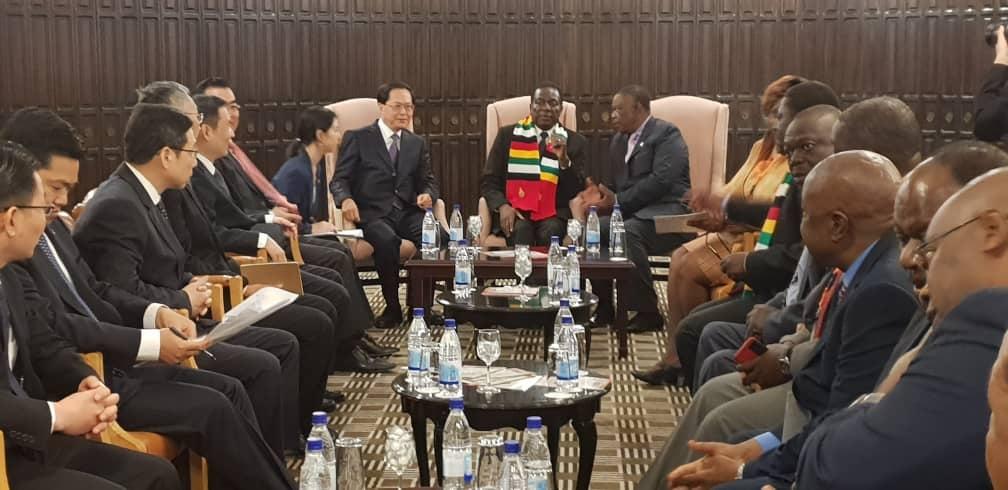

There’s little question that Mnangagwa—who replaced Mugabe in November 2017—is seen to fit the bill. Among friends, he is a self-professed Sinophile, claiming to be the first black African to receive military training in China and boasting that he has known four generations of Chinese leaders. He reportedly sent one of his sons to China for five years, so that he might become fluent in Mandarin and also acquire military training.

Indications are that Mnangagwa leans toward a hybrid economy akin to the Chinese model, whereby genuine competition and dynamism will sit alongside crony capitalism and civil-military corporatism. There is no reason to doubt his message that Zimbabwe needs to restore economic sanity.

Neither is there reason to think that sweetheart deals and kickbacks will not be part of the equation on some of the bigger projects. In 2010, as minister of defence, Mnangagwa oversaw the formation of Anjin, a diamond-mining joint venture between Chinese private investors and a letterbox company that masked the Zimbabwean military’s stake. He is alleged to have personally benefited from this arrangement. Anjin was ejected from its concession during the turmoil of Mugabe’s last couple of years, but Mnangagwa has since reinstated it.

Beijing will not expect the exclusion of Western companies from the market, but will hope that economic recovery will enable the Zimbabweans to afford the soft loans, underwritten by the Chinese government, that give Chinese companies an edge. A US$485 million agreement signed in 2016 between Huawei and state-owned telecom NetOne is the kind of deal they will want to gain traction.

Another edge that will prove welcome is the continued opportunity to bribe. The fact that Chinese rivals such as Huawei and ZTE occasionally rat each other out—as they have apparently done in Zimbabwe—is of little concern while anti-corruption initiatives remain selective and Western-listed companies are cowed by the massive fines that can be imposed on them by home governments when they’re caught playing the same game.

Moving beyond the description of Sino-African relations as ‘complex’—especially with a case file confined to Zimbabwe—is a hazardous affair. Much more, prognostications. But the foolish or brave might put it thus: African governments and the Chinese will use one another in an effort to build their economies and reinvent klepto-authoritarian political systems. If the West sinks further into its own slough of cultural confusion and conflict, it will be unable to offer a viable or attractive alternative.