As Palau approaches its November presidential election, expect China to intensify its influence operations in the strategically crucial Pacific island state. Much is at stake: the election may determine Palau’s future relationship with Taiwan and its stance towards the People’s Republic of China.

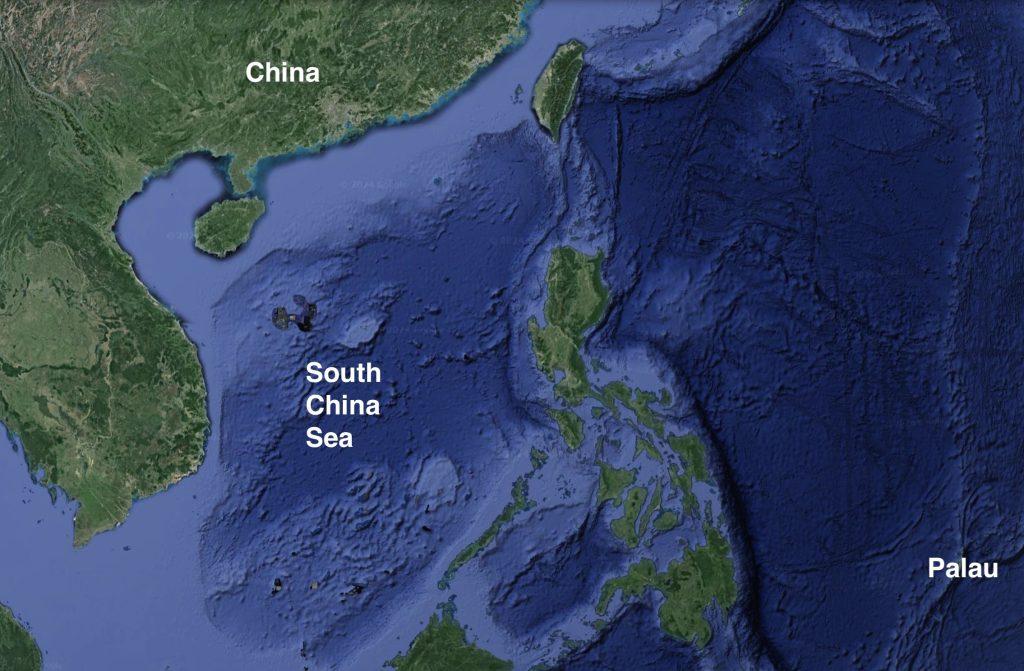

The prospect of intensified Chinese influence operations increases the risk of a pro-Beijing president taking office in a country that’s just 2,400 kilometres from the South China Sea, is a key ally of the United States and supports it by hosting a major air base, a naval base and a newly installed radar with extremely long range.

Palau has already been the target of Chinese information operations, and there are several indicators that those efforts are now being directed at the election. China is likely to implement refined tactics that it previously used in the recent Philippine and Taiwan presidential elections. Urgent action to guard against interference is crucial to protect Palau’s democratic process and sovereignty as a whole.

The two major candidates confirmed to be in the race are current president Surangel Whipps Jr, who is pro-US but less popular with the public overall, and former president Thomas Remengesau Jr, who has several ties to China and is favoured to win.

A recent report by the US State Department’s Global Engagement Center outlines Beijing’s five main tactics to manipulate the information space. One tactic—propaganda and censorship—is of primary relevance in Palau.

Propaganda and censorship have been used by China to directly manipulate its messaging worldwide. For example, China has made several attempts to gain a foothold in Palau’s domestic media ecosystem.

As detailed in an OCCRP article, ‘Failed Palau media deal reveals inner workings of China’s Pacific influence effort’, a local news outlet has been linked to CCP-associated individuals and narratives several times in the past. The outlet, Tia Belau, is one of two widely circulated domestic newspapers in Palau. Its owner, founder and recently declared presidential candidate, Moses Uludong, is a prominent figure in Palauan media and has been documented on multiple occasions advocating for closer relations with China.

In 2018, Uludong joined the Palau Media Group—a venture led by Tian ‘Hunter’ Hang, a key player in China’s strategy to exert soft-power influence in Palau. While the Palau Media Group did not succeed upon launch, Tia Belau has since been used to publish pro-China content and is known as a China-sympathetic media source. Beijing’s blatant investment in local media outlets, such as Tia Belau, minimises the potential exposure of unfavourable stories and pushes very specific dialogues that support Chinese interests.

China uses a variety of censorship tactics that could disproportionately affect a small, relatively isolated population such as Palau. They include information disturbance (flooding the information space with false narratives to create doubt and uncertainty), discourse competition (shaping cognition by manipulating emotions and implanting biases), public opinion blackout (using bots to flood social-media spaces with a specific narrative to suppress opposing views), and blocking of information (technical blockades and physical destruction of narratives unfavourable to China) to censor the information space, several of which have been increasingly seen in Palau leading up to the election.

Tracking and identifying specific instances of China-influenced messaging is challenging, as it is with all forms of misinformation. Nonetheless, it’s clear that China has significantly increased its focus on Palau in the months before the election, leveraging economic pressures to promote China-favoured narratives. Combined with the evidence collected from Chinese involvement in other recent elections, there’s little doubt that China is using social media and news outlets to reshape ‘China’s story’ within Palau, aiming to influence the political outcome of the election.

Given Palau’s small population, geographic location and susceptibility to corruption, combating Chinese election interference will be challenging. Tactics similar to those implemented in Taiwan, such as amplifying local conflicts, using local proxies, media outlets and social-media accounts, exploiting domestic actors with ideologically aligned views, and relying on artificial intelligence to promote desired CCP messages and outcomes, should be expected. Direct media interference and disinformation campaigns, as seen in the Philippines, are also highly probable.

Countermeasures inspired by those implemented in Taiwan could help Palau build resistance to China’s propaganda. Targeted training for Palauan journalists and media professionals on countering disinformation could help bolster resilience and incentivise responsible journalism. Palau’s government could prioritise debunking disinformation with counternarratives, prosecuting individuals involved in large-scale disinformation campaigns, or implementing legislation similar to Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code or Taiwan’s Anti-Infiltration Act. Finally, Palau could encourage civil-society initiatives that track and counter disinformation, as well as media literacy programs in schools that teach students how to resist false narratives.

China’s information operations in Palau highlight the need for the nation to adopt effective countermeasures as it approaches its presidential election this autumn. By learning from the experience of Taiwan and the Philippines, Palau can enhance its resilience and protect its information environment.