Our new ASPI report, Borrowing mouths to speak on Xinjiang, explores how the Chinese Communist Party uses foreign social media influencers to shape and push messages domestically and internationally about Xinjiang that are aligned with its own preferred narratives.

This seemingly new strategy is being deployed on US platforms like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter via party-state media and diplomatic accounts and even in briefings by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But while this incarnation of the strategy with its use of influencers is new, it’s actually part of an old strategy that the CCP has put to use since its inception. This is how Zhu Ling (朱灵), a former editor-in-chief of China Daily, described the strategy in a speech celebrating the 30th anniversary of his newspaper: ‘We have always attached great importance to “borrowing a mouth to speak” and used international friends to carry out foreign propaganda.’

Our report examines key instances in which Chinese state entities have supported influencers in the creation of social media content in Xinjiang or amplified influencer content that supports pro-CCP narratives. This content goes beyond the normal public diplomacy sponsored by governments and broadly seeks to debunk Western media reporting and academic research, refute statements by foreign governments and counter allegations of widespread human rights abuses such as the mass incarceration of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang.

The addition of foreign social media influencers on orchestrated tours that have traditionally been made up of party-state media, amenable diplomats and friendly foreign journalists reflects a willingness among Chinese officials to introduce innovations into Beijing’s external communication strategy.

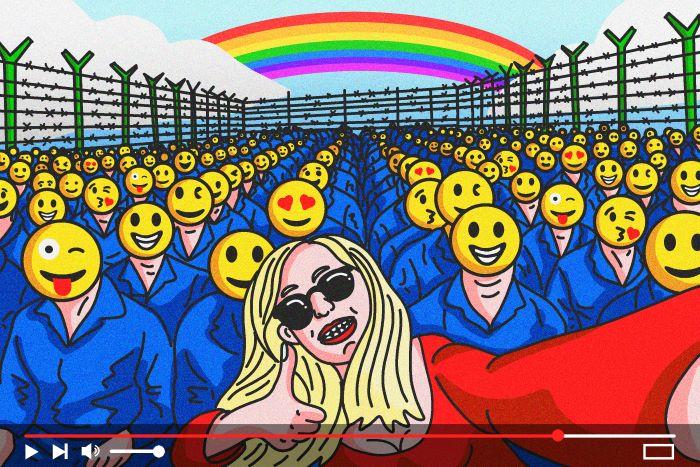

Likewise, the amplification of influencer content about Xinjiang on social media by party-state media and diplomatic accounts is used as part of campaigns to distract from and foment confusion over allegations of human rights abuses there, while reframing the discussion of issues that the CCP is particularly sensitive about.

We analysed hundreds of YouTube videos depicting trips to Xinjiang made by foreign influencers. Just as many tours of Xinjiang are largely directed by party-controlled institutions and government bodies, our research suggests that some of the locations shown in the foreign influencers’ videos are also chosen by state entities.

When the locations were not chosen by the Chinese state, our analysis found that detention centres where Uyghurs are held were sometimes accidentally filmed. Our analysis of one video, filmed by a vlogger from Singapore, found that he filmed seven separate detention facilities in a 15-minute YouTube video showing his aerial descent into Urumqi International Airport.

The research also examines how the CCP’s use of foreign influencers presents a new challenge to global social media platforms, in particular their efforts to identify and label state-affiliated accounts. Social media platforms will need to craft and implement policies to identify accounts with links to states or content that has been directly facilitated by states, but the task won’t be easy.

The use of foreign influencers creates a degree of plausible deniability for the CCP’s international-facing propaganda—a strategy adopted in the knowledge that foreign voices are more likely than official CCP spokespeople to penetrate and resonate with target overseas populations.

This activity is happening at the same time as the ability of foreign governments to conduct legitimate online public diplomacy within China—such as posting on Weibo—is being curtailed and censored. In combination, this creates a potent one-way vehicle for the extraterritorial projection of the CCP’s political power.