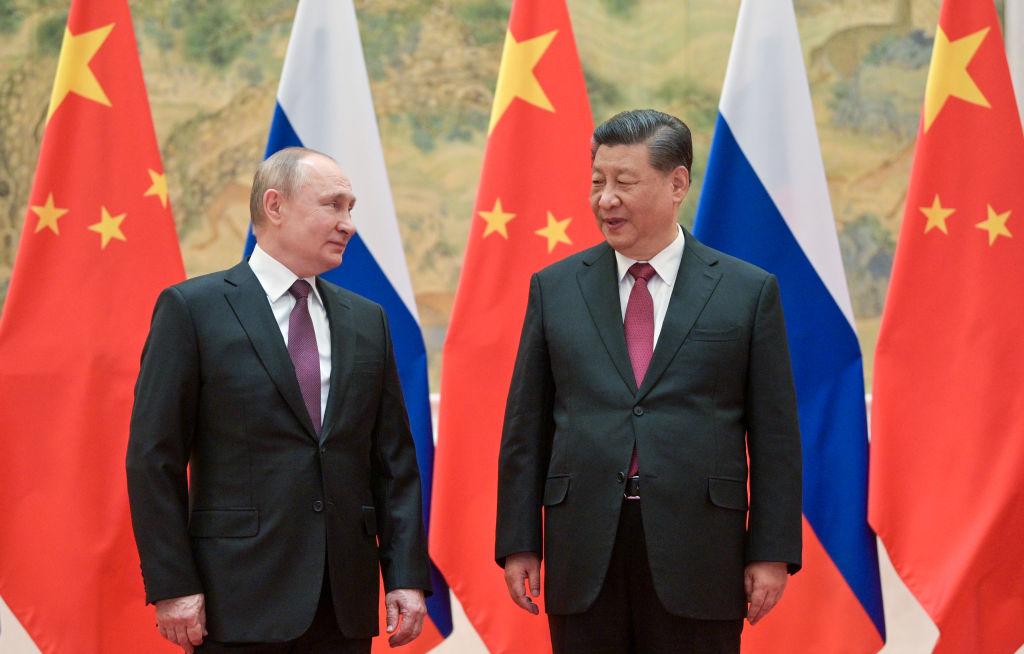

China and Russia may be allies in autocracy, but their attitudes towards engagement with the global economy could not be more different.

Whereas Vladimir Putin has devoted the past 20 years to making Russia’s economy as bulletproof as he can, China has pursued as much growth as globalisation can deliver.

Announcing China’s 2022 growth target of 5.5% over the weekend, Premier Li Keqiang underlined the Chinese Communist Party’s continuing commitment to the open world markets that are being slammed shut to China’s Russian ally.

China would continue to pursue its Belt and Road Initiative and would ‘deepen multilateral and bilateral economic and trade cooperation’, he said.

While the international outlook was ‘increasingly volatile, grave and uncertain’, Li saw foreign investment as an important contributor to China’s domestic economic growth. ‘The vast, open Chinese market is sure to provide even greater business opportunities for foreign enterprises in China,’ he said.

For China’s rulers, history is marked by extended periods of chaos and revolution. Governing the largest population in the world has been difficult for millennia. The sharpest focus of the communist dynasty has been on the ‘century of humiliation’, when foreign powers occupied the banks of the Huangpu River in Shanghai and imposed their will on the fading Qing dynasty, after which vast reaches of China were occupied by invading Japanese forces.

The CCP sees elevated levels of economic growth as the guarantee of social and political stability. Xiang Dong, deputy head of the Research Office of the State Council, commented on the growth target:

Stable economic conditions act as the basis. If the economy turned unstable, employment and people’s incomes would be hard to stabilize, while risks and ‘landmines’ could manifest themselves.

Achieving economic growth of around 5.5 percent will lay the foundation for expanding employment and raising incomes, making sure that the economy continues to stay within a reasonable range.

For Putin, the object lessons guiding his economic policy have been the chaos in which Russia found itself after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, followed by the repeated imposition of economic sanctions by the West in response to Russian aggression towards former Soviet states.

Russian inflation hit 874% in 1993 and it was still at 88% in 1999, the year Putin was appointed prime minister. Russia faced economic collapse in 1998, defaulting on its international debts with soaring unemployment. Over the first eight years of its post-Soviet life, the economy contracted 30%.

Putin was helped by the oil price. It rose from a 1998 low of just US$20 a barrel to US$50 a barrel by 2000 and then, with some volatility, continued rising to a zenith of just under US$180 a barrel in 2008. While the global financial crisis hurt, the oil price has generally remained above US$60, except for a brief pandemic plunge back to US$20.

The Russian government didn’t squander its petro-dollars, running a tight budget balance and building up reserves. Debt was paid off. Many of the assets handed to oligarchs on the break-up of the Soviet Union were renationalised.

Russia first started to feel the pressure of sanctions in 2008, following its invasion of Georgia and then, again, in 2014 following its invasion of Crimea and backing for separatist movements in Ukraine’s Donbas region.

Russia responded with efforts to make its economy as sanction-proof as possible. Building up large foreign exchange reserves was part of that effort; it was not anticipated that those funds could be frozen.

There were further rounds of US sanctions in 2018 following the use of military nerve agent in an attempted assassination in the UK of former spy Sergei Skripal and also over the Russian interference in the 2016 US election. It was following those moves that Russia sold its holdings of US Treasury bonds.

While China was out to exploit every advantage that membership of the World Trade Organization could possibly bring it, Russia was focused on selling oil, gas, specialist metals, wheat and a few other commodities, locking in its customers as effectively as it could.

Russia gained membership of the WTO in 2012 but has been a relatively passive member. Its only free-trade agreements are with Vietnam, Serbia, Singapore and Iran, and those are through the Eurasian Economic Union, a body it sponsored to drive trade with former Soviet states like Belarus and Kyrgyzstan.

Contrast that with the hyperactive trade diplomacy of China, pushing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, joining a Singapore-led digital trade initiative, pushing to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and seeking an investment agreement with the European Economic Union. It also has 16 bilateral free-trade deals and is negotiating a further eight.

Russia is engaged in globalisation, but as a provider of commodities sold on open markets for which there’s global need, particularly in Europe and China.

Economic historian Adam Tooze, whose depth of knowledge of the Russian economy makes his commentary an indispensable reference during the Ukraine crisis, argues that far from pursuing growth, Putin operated an austerity campaign to strengthen state finances, with the budget swinging from a large deficit to a substantial surplus over the past four years.

Since 2009, Russia has averaged growth rates of only around 0.8%, less than half the growth of other Eastern European nations and below the advanced nation average.

Growth and prosperity, which are fundamental for China, are subordinated to order and resilience in Russia.

It’s too soon to tell how successful Russia’s attempts to insulate its economy from Western sanctions will prove. Russian authorities have the latitude to respond to the sanctions with a generous stimulus package if they can break from their parsimonious instincts; however, there are suggestions that the Russian motor industry and its airlines will grind to a halt over coming months because of lack of access to Western technology.

Beijing will be cautious about breaching Western sanctions on Russia. It has far too much to lose. China wants to continue to profit from globalisation in an increasingly isolationist age.