The news that China and Cambodia may have signed a secret agreement for Beijing to have long-term control over part of Cambodia’s Ream naval base, with the right to base People’s Liberation Army naval vessels, military supplies and personnel, has caused a spike of concern about China’s growing military presence across the ASEAN region. As regional expert Carlyle Thayer has observed: ‘China is likely to establish a military foothold in Cambodia as a result of a gradual process whose pace will be determined by the amount of political resistance in Cambodia and the region.’

The agreement is for 30 years, with automatic renewals every 10 years after that.

Concerns have also been expressed about China’s ability to exploit the nearby Dara Sakor international airport, being built by China’s Union Development Group. It’s located in the middle of the Cambodian jungle in the Koh Kong region, and the runway is clearly being designed to support large military aircraft as well as fighter aircraft.

The naval base and airport add to the 20% of Cambodia’s coastline now leased to Chinese companies, and make possible further Chinese military expansion at the expense of Cambodian citizens and sovereignty.

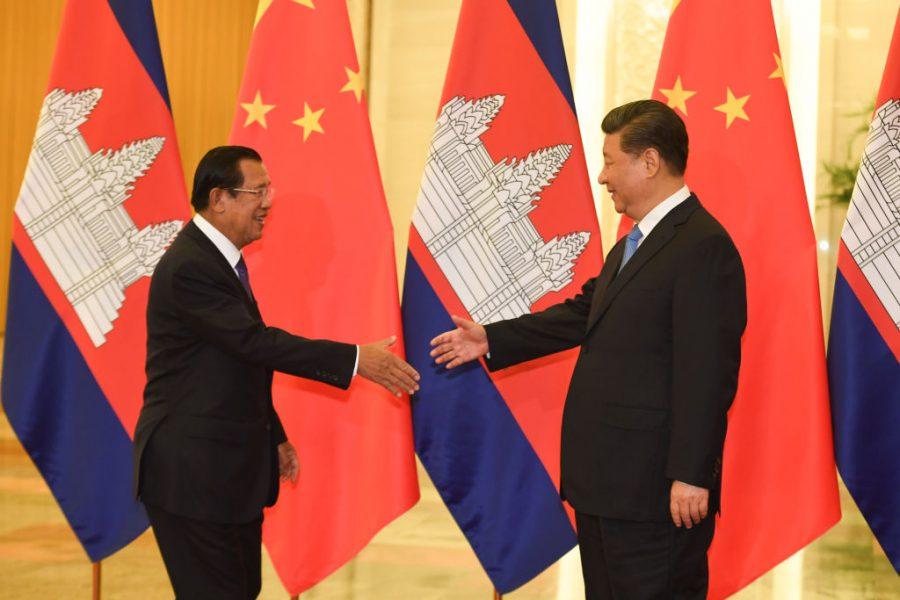

The leaked agreement reinforces the broadly held view that Cambodia has slipped further into Beijing’s strategic orbit. Thayer argues that the Ream project is indicative of a broader trend which sees Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen make ‘a compact with the devil to ensure his regime’s survival’. He argues that that bargain will lead to Hun Sen ultimately ceding control on decisions involving China’s economic presence in Cambodia to Beijing, noting that, ‘Cambodia is no longer a sovereign actor; it may make requests for Chinese assistance, but it is China that determines what projects are funded and which projects are not.’

A key factor behind the agreement is China’s debt-trap diplomacy driven by its Belt and Road Initiative. Hun Sen has accepted substantial Chinese aid as part of signing up to the BRI, including US$600 million in loans, and Beijing has offered a further US$2 billion to enable it to build road and rail networks across Cambodia.

The combination of Chinese economic loans and Chinese-built ports, airports, and road and rail links across Indochina not only gives Beijing strategic influence and enables it to coerce its neighbours into virtual vassal status, but also enhances the PLA’s mobility and, ultimately, allows a forward strategic presence for China’s military.

This is what the BRI is all about. It’s far from being a ‘win–win’ outcome through interdependent development that benefits all. Instead, it’s simply a win for a rising hegemonic China that seeks to reassert its role as a 21st-century Middle Kingdom.

An expanding Chinese military presence in Cambodia is a game-changer for the security interests of ASEAN. ASEAN was conceived to enhance regional resilience, but any Chinese military facility—even a dual-use facility—is likely to be a disintegrative factor because it could potentially facilitate external military coercion against member states.

The most immediate impact of Chinese access to Ream would be on the unresolved maritime territorial dispute between Cambodia and Thailand generated by differences over a border agreement dating back to 1907, and the potential for Chinese access to oil and natural gas deposits in the disputed region. The presence of Chinese naval forces operating from Ream will alarm Thailand and raises the prospect of Chinese interference in the dispute.

PLA Navy vessels—or well-armed quasi-military forces such as the Chinese Coast Guard and maritime militia—could adopt a more assertive profile on the high seas in the Gulf of Thailand, and into the South China Sea.

Chinese naval forces deploying out of Ream could, for example, patrol near the Natuna Islands to protect illegal Chinese fishing activities, which have been challenged by Indonesia in the past. It may also encourage China to more aggressively assert that the so-called nine-dash line extends south of these Indonesian territories. If that action was supported by the PLA Air Force, Indonesia’s ability to respond to illegal fishing around the islands would become more challenging. Charles Edel notes that:

If you have a naval base in Cambodia, it means the Chinese Navy has a more favorable operational environment in the waters surrounding Southeast Asia … You have all of a sudden a mainland Southeast Asia potentially sitting behind a defensive Chinese military perimeter. This is by far the biggest implication.

Vietnam would certainly feel the pressure. Ream is about 100 kilometres from the Vietnam–Cambodia border, and Chinese warships could operate south of Vietnam before turning northeast to support Chinese activities along the Vietnamese coast in the disputed Spratly and Paracel island chains. In the air, the combat radius of PLA Air Force J-10Cs flying from Dara Sakor, using internal fuel, would bring all of Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore within range, as well as parts of Indonesia and Myanmar.

A Chinese military base in Cambodia could also give China a greater ability to choke off maritime trade flows in any future blockade of Taiwan as a prelude to a Chinese invasion in coming years. Conversely, it would increase China’s chances of breaking a US-imposed distant blockade in such a scenario, denying the US and its allies—including Australia—an ability to operate unmolested across maritime Southeast Asia.

A Chinese military base hosted in the middle of ASEAN is a tangible wedge into ASEAN solidarity and security. If ASEAN is to remain an effective grouping, its other member states must act to prevent Cambodia from undermining their collective security through this secret basing agreement.

Cambodia’s move supports China’s ability to project maritime power along the maritime silk road into the far seas and oceans of the Indian Ocean. It acts as the next ‘pearl’ along what is now clearly emerging as a genuine ‘string of pearls’ that begins with Djibouti and extends through Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, and now Ream in Cambodia. Each facility is adjacent to vital maritime choke points or astride critical sea lanes of communication.

Alfred Thayer Mahan would argue that sea power is inherently a means to economic dominance and thus political influence. In Red Star over the Pacific, Toshi Yoshihara and James Holmes note that a Mahanian approach to sea power starts by recognising ‘the necessity to secure commerce, by political measures conducive to military or naval strength … [M]ilitary access constitutes a guarantor of diplomatic access, while diplomatic access backed by military force is necessary to ensure commercial access and the economic blessings it bestows.’

Possessing forward bases like Ream means that Beijing will be far better placed to control the critical economic heartland of the planet that is centred around maritime Southeast Asia, keeping the sinews of global maritime commerce through this vital region firmly in its grip.