The Chinese Communist Party has a long history of engagement with criminal organisations and proxies to achieve its strategic objectives. This article provides new evidence of the development of a CCP-linked influence-for-hire industry operating in Southeast Asia. This activity involves the Chinese government’s spreading of influence and disinformation campaigns using fake personas and inauthentic accounts on social media that are linked to transnational criminal organisations.

To investigate how the CCP is creating or acquiring inauthentic accounts for use in its influence operations, including those currently targeting Australia, ASPI traced some of them to a network of Twitter accounts advertising links to Warner International Casino (华纳国际赌场), an illegal online gambling platform operating out of Southeast Asia and linked to Chinese transnational criminal organisations.

ASPI’s first report on coordinated information operations linked to the Chinese government, published in 2019, found that the campaign against the Hong Kong protests used repurposed spam or marketing accounts, which were used by CCP operators to replenish their covert networks. Those personas are typically unconvincing but are cheap, created en masse and quickly adapt to avoid automated spam-detection systems. They are partly why Chinese government entities are thwarting social media platforms’ latest efforts to counter influence operations and other coordinated inauthentic behaviour.

In the recent campaigns targeting Australian political discourse discussed in the first part of this report, many of the accounts impersonating and targeting ASPI use Bored Ape Yacht Club images as profiles. Those profiles are popular across many spam networks related to NFTs (non-fungible tokens), but they’re also used by multiple accounts posting links to Warner International (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A CCP-linked account targeting ASPI with a Bored Ape profile (left) and a Twitter account mostly promoting Warner International with a Bored Ape profile (right)

Likewise, accounts promoting Warner International are using similar AI-generated profile images on inauthentic accounts involved in CCP influence operations. A Twitter account named ‘Cassandra Anderson’ has a profile image that appears to have been generated by ‘This Artwork Does not Exist’ and matches other similar AI-generated artworks used as profile images by accounts previously linked to the CCP (Figure 2).

Figure 2: CCP-linked accounts with AI-generated profiles claiming that the US is an irresponsible cyber actor (left) and a Twitter account promoting Warner International (right)

At times, the same images are used by both CCP-linked accounts and accounts promoting Warner International. The Twitter account of ‘Neda’ is involved in a CCP-linked online campaign that seeks to interfere in the Australian political discourse (including through ongoing heavy use of the #QandA and #auspol hashtags), such as by amplifying claims about sexual abuse in Australia’s parliament. This account shares the same profile image and cover photo as another Twitter account advertising Warner International, which has since been suspended (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A CCP-linked account interfering in Australian political discourse (left) and a Twitter account promoting Warner International (right)

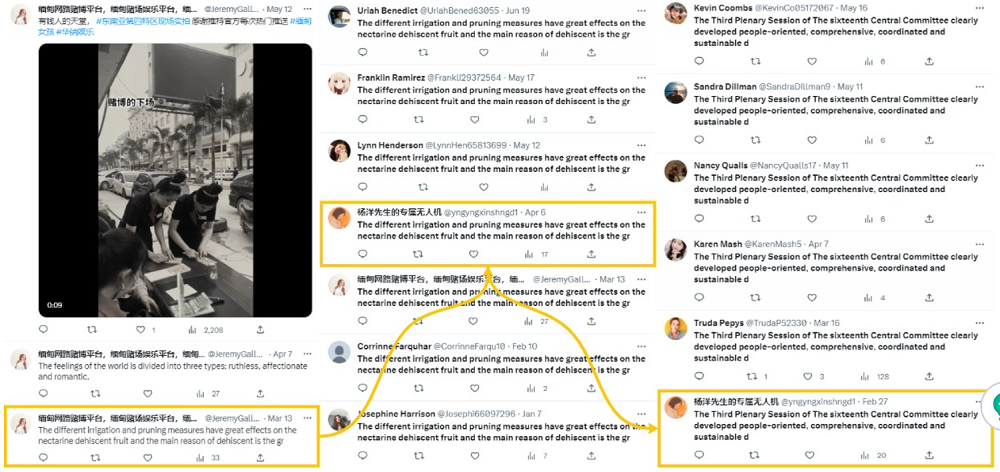

In addition to having similar profile images, these accounts behave in the same way and likely belonged to the same pool of accounts when they were created. The Twitter account with the handle ‘JeremyGallache6’ is a representative example of this group. It was created in March 2023 and the bio links to Warner International. The account’s first tweet is cut off mid-word and appears to have been automatically translated from Mandarin. The text of that tweet is replicated by dozens of other accounts with similar profile images as their first tweets, which have also posted CCP propaganda (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Twitter timeline of ‘JeremyGallache6’ promoting Warner International (left) next to a list of accounts replicating JeremyGallache6’s first tweet (middle), including ‘yngyngxinshngd1’, which has posted CCP propaganda replicated by other similar accounts (right)

Another example is ‘Belinda Anderson’, who says that Falun Gong, a persecuted religious organisation in China, ‘should not appear’ and is a ‘cult’. ‘Belinda’ belongs to a group of accounts promoting Warner International that all have the same first few tweets. In the past year, accounts likely linked to Chinese police officers have displayed similar posting patterns. ‘Avery Alfred’, a CCP-linked account, joined Twitter in March 2023. Its first tweet is replicated by dozens of other accounts with similar profile images (Figure 5), like the accounts promoting Warner International.

Figure 5: Profile images of four accounts posting links to Warner International (left) and profile images of four accounts linked to CCP covert influence operations targeting Australia (right)

Warner International Casino appears to be associated with a casino owned by the Warner Company and based in the city of Laukkaing in northern Myanmar near the border with Yunnan Province, China. Twitter accounts posting links to its online gambling platform share the same logo as the Warner Company (Figure 6), and videos of the gaming room shared online match the images on Warner International Hotel’s website.

Figure 6: A Twitter account posting videos filmed inside Warner International (left), an image of the casino on the gambling website that was shared by Warner International Twitter accounts (middle) and an image of the casino on Warner International Hotel’s official website (right)

Warner International is a typical illegal online gambling platform that lures Chinese-language speakers inside and outside of China. Online users of the website place bets through a live broadcast of the casino and share the same gaming table as in-person gamblers.

On Reddit, accounts promoting links to Warner International post misleading explanations when the website stops its online users from withdrawing money from the platform. The number of such posts suggests that the users are often locked out of their accounts and lose access to their winnings and initial deposits. The accounts also offer counter ‘hacking technical teams’ when users’ online gambling accounts are supposedly ‘hacked’. These types of services have been reported to be secondary scams.

Chinese police officers are aware of Warner International’s operations. A 2021 Beijing Daily article revealed that officers from the Mudanjiang City Public Security Bureau in China’s northernmost province were investigating and arresting affiliates involved with Warner International’s gambling website (Figure 7). The article suggested that Warner International was operated by overseas gang members who were smuggling Chinese citizens into Myanmar to participate in illegal gambling or to work at the casino and entice other Chinese citizens to gamble online.

Figure 7: Screenshot provided in an article posted by Ningbo Police

There are a number of possible explanations for this development. It’s conceivable, for example, that elements of China’s security services are opportunistically acquiring inauthentic accounts from criminal networks, such as Warner International, to reinforce their covert influence operations online. The CCP has a history of engaging with criminal organisations, including triads in Hong Kong and Macau, to attain its political goals. For example, the head of China’s Ministry of Public Security, Tao Siju, said in 1993 that, as long as triads in Hong Kong were ‘patriotic’, the ministry should ‘unite with them’ to uphold Hong Kong’s prosperity following its handover from the UK government. That statement was coincidentally made a few days after a new nightclub called Top Ten had opened in Beijing. The club was co-owned by Tao and Charles Hueng, the head of the Sun Yee On triad, illustrating the links between senior security officials and prominent criminal figures.

More recently, Chinese high rollers linked to reported underworld figures have been entwined in alleged foreign interference operations in Australia operating out of casinos. Likewise, Warner International is one of many that have been reported to be bases for illegal online gambling and scam operations, including the Jinshui compound—a complex implicated in reports detailing online scams and gambling operations (which has also been linked to Cambodian officials, CCP United Front–affiliated figures and Suncity Group).

But it’s also possible, for example, that what we’re seeing here is an overlap in the outsourcing (of private contractors) being done between China’s security services, which need to maintain their global information operations, and those groups using inauthentic accounts to promote criminal networks, such as Warner International. While not exactly the same, there are similarities in what US-based news media outlet ProPublica unearthed in 2020 regarding a Beijing-based internet marketing company, OneSight Beijing Technology, which it found had ties to the Chinese government and was involved in covert influence operations on social media. ProPublica’s examination of an interlocking group of accounts linked to OneSight Beijing Technology found that some were impersonating the US government–funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia. We observed the same tactic in the recent campaign targeting ASPI, Safeguard Defenders, Badiucao, Vicky Xu and others.

The Chinese government is expanding its digital infrastructure to conduct online covert influence operations outside of mainland China, so such developments would also be consistent with behaviours that some social media platforms are seeing. For example, Twitter’s notes to its Moderation Research Consortium in 2022 said that technical indicators of a pro-CCP network suggested that it was being operated from Singapore and Hong Kong.

We know that the Ministry of Public Security is one of the primary agencies in China responsible for covertly manipulating global public opinion on social media. In scaling up its influence operations by purchasing inauthentic social media accounts from criminal networks, using such accounts, or both, it is enabling other criminal activities, such as illegal gambling, human trafficking and telecommunication crimes.

There are many things the Australian government should be doing to counter this malicious activity. Just as cybersecurity, particularly to combat intellectual property theft for commercial gain, was made a bilateral issue by Australia, so should this issue of cyber-enabled foreign interference.

The Australian Federal Police, for example, needs to raise the issue of foreign interference targeting Australian citizens and organisations, including bounties placed on Australian residents for exercising freedom of speech, with its counterparts in China during their law-enforcement working groups. The AFP should also consider these developments in the light of its necessary but increasingly complicated intelligence-sharing relationship with the Ministry of Public Security.

Government agencies, investigative journalists and civil-society organisations around the world have an important role to play in investigating this criminal–state nexus further and raising public awareness about such malicious regional activity. This is an opportunity for global law enforcement agencies, including Interpol, to increase their collaboration with local authorities to tackle cyber-enabled financial crime, human trafficking and corruption in the region.

In addition, governments and regional bodies need to apply greater international pressure on Cambodia and Myanmar to crack down on these types of activities. Governments should coordinate joint Magnitsky-style sanctions to target key figures in Chinese transnational criminal organisations and the political elites in those countries affiliated with, for example, cyber-slave compounds, which are becoming more common in the region. By disrupting those criminal operations, governments would also be combating an industry that’s spawning inauthentic accounts for states to peddle propaganda and disinformation.

The growth of a regional, criminal and state-linked influence-for-hire industry is yet another challenge for the Indo-Pacific, which needs strategies and new mechanisms to counter and deter the increase in hybrid activity in the region. Establishing an Indo-Pacific hybrid threats centre, similar to Europe’s equivalent (the Hybrid Threats Centre of Excellence in Finland), would help to build regional capacity, coordinate responses and enhance regional stability.

The threats we face as a society are no longer limited to violence, espionage and interference conducted in person—whether by individuals, state entities or criminal groups—but are increasingly enabled by digital personas, inauthentic accounts and coordinated networks that can reach anyone globally and instantly. AI experts have been warning governments to prepare for the impact that AI will have in supercharging disinformation and cyber-enabled interference. The question for policymakers will increasingly be about how they counter malign actors that are difficult to attribute or distinguish from legitimate actors online—especially when those actors operate across a booming ecosystem of digital platforms headquartered in different countries. This question will become harder and harder to answer without the right rules and legislation in place.

Once again, the solution is not passivity or silence. The Australian government’s current approach will not hold as we enter an era in which we need to protect our democratic institutions and our public discourse from cyber-enabled foreign interference in what will soon be an AI-saturated world.