On 30 March, the Chinese embassy in Fiji made an overt and concerning attempt to influence the Pacific information environment, seeking to shape perceptions around Chinese policing behaviours and reported links to organised crime in Fiji.

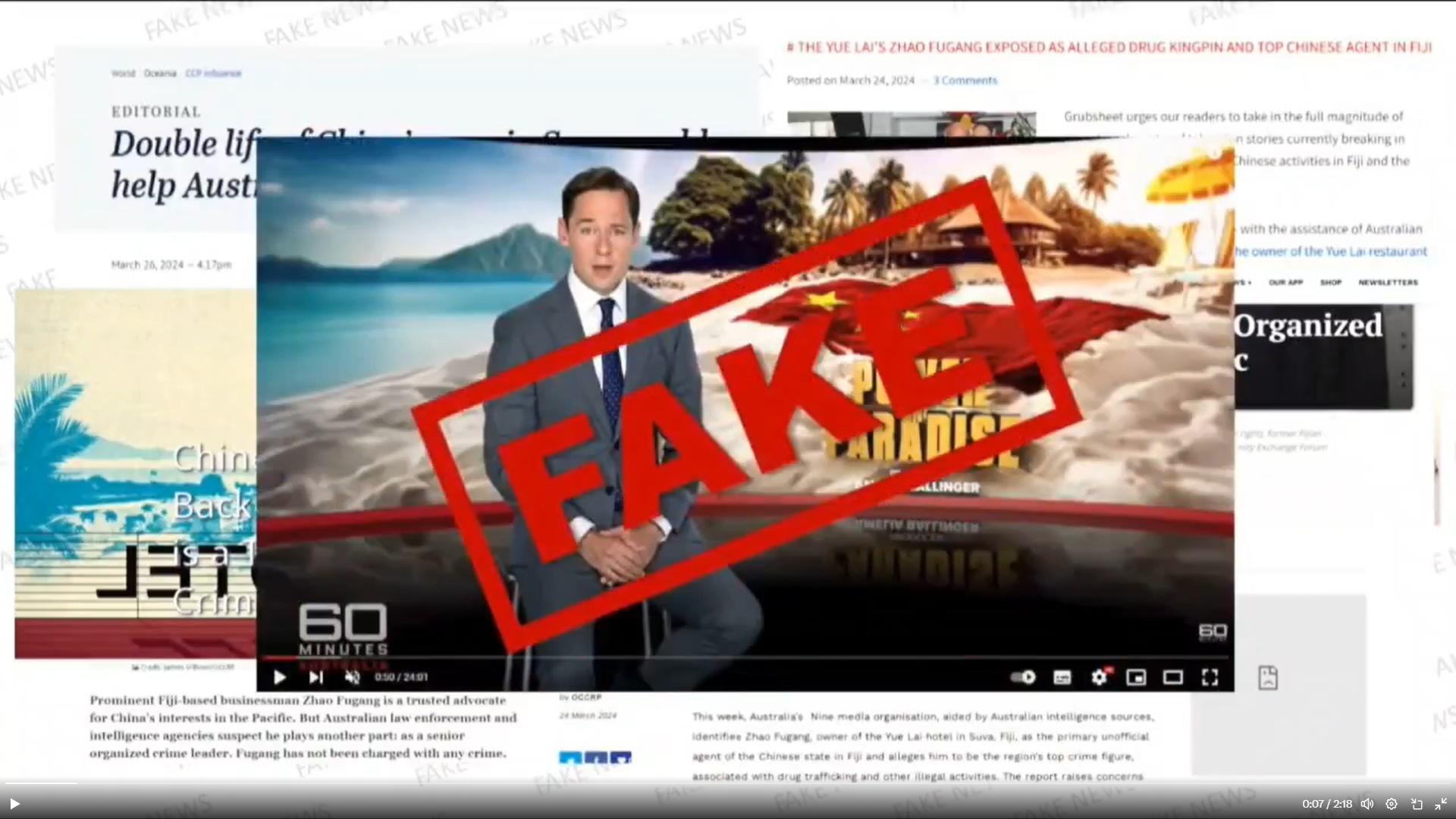

Responding to a 60 Minutes Australia episode aired on 24 March 2024 that investigated Chinese policing and organised crime links in Fiji, the embassy produced and published a two-part video essay muddying the waters around the allegations.

This was part of its continued efforts to undermine trust in traditional partners and Western media in the region.

The 60 Minutes investigation drew on two main sources to make a case for China’s malign influence in Fiji. The first was a report by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), an international NGO of investigative journalists. The OCCRP report looked at the activities of Suva-based Chinese businessman Zhao Fugang and his designation as a priority target by Australian authorities for alleged involvement with organised crime.

The second piece of the puzzle was a video produced by Chinese police lauding a rendition operation of alleged Fiji-based Chinese cyber criminals.

The rendition video, originally discovered by ASPI analysts, cast a spotlight on a controversial policing memorandum of understanding between Fiji and China. While the rendition video itself dates back to 2017, the timing of the 60 Minutes production followed the announcement that Fiji had decided to stick with the agreement, though some terms have been changed. Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka had already decided on the repatriation of Chinese police embedded in Fiji and allowing Fijian forces to continue training in China.

The 60 Minutes episode did not address the resolution of the memorandum’s status but spurred further media attention, which prompted the embassy to respond with two videos.

Despite enthusiastic production quality, the embassy’s videos had limited impact. While the first attracted more than 80,000 views on X, the second got only 40,000. Although viewer demographics cannot be determined, traceable public engagement suggested limited reach on online platforms. The videos were quoted or reposted by 62 unique X accounts that ASPI had assessed as based in the Pacific. These Pacific accounts were mostly linked to Fijians. Most quotes from Pacific-based accounts were broadly supportive of the videos, but few directly criticised the Australian government or Western media or meaningfully reflected upon the contents of the videos.

Beyond the Pacific, there was significant interaction from Chinese-language or China-based accounts. However, these reposts were largely from Chinese Communist Party officials or likely inauthentic accounts. Some such accounts had all reposted the same stream of Chinese state media articles; others were new accounts with no activity aside from reposting the embassy videos. While Pacific-based accounts were more likely to quote the embassy videos, engagement from all Chinese-language accounts and an overwhelming majority of accounts of unclear origin were purely reposts, a likely indication of attempts to inauthentically expand the reach of the posts.

The embassy tagged several Fijian media outlets in its posts on X, but they did not engage with the content.

Messages similar to those in the embassy’s videos were published in CCP state media and in certain Fijian online news outlets, such as the Fiji Times and Fiji Live. Of 17 articles addressing the issues raised by the 60 Minutes episode published by Pacific media online within two weeks of the broadcast, seven came from the Fiji Times and Fiji Live. Most media articles produced by Pacific outlets focused on the organised-crime and drugs angle, rather than the policing memorandum of understanding. This highlights the importance of these issues to the Fijian people, compared with the China-versus-the-West narrative pushed by the embassy’s videos.

China’s messaging failed to have an impact elsewhere online, such as popular public Facebook groups. No CCP state media article covering the policing issue was reshared on a public Facebook group or page in the Pacific region. Of the original Western media articles, it was the OCCRP report that gained the most interest through reshares in the region.

While there was a disconnect between the anti-Western narratives pushed by China and the region’s interest in corruption and organised crime, this is not a reason to be complacent. Australia and other foreign partners cannot sit idly by and allow baseless accusations against media organisations to continue. The CCP’s ability to publish statements critical of Australia through local media has the potential to undermine Australia’s reputation in Fiji and the region, particularly as several influential figures in the Pacific islands reposted the embassy’s content with neither additional commentary nor apparent scrutiny.

The time and effort invested in the production of these videos is an escalation of sophistication behind the CCP’s approach to criticising Australia and Australian media. That level of sophistication has rarely, if ever, been seen in the region before. This new creative effort to influence the information environment should be cause for concern.

Complacency and inaction cannot guarantee that future efforts will have the same limited effect. Pacific governments and media organisations are calling for more training on understanding disinformation tactics, on fact-checking information and on sifting through online noise. As a trusted partner, Australia can play an important role in capacity-building for a resilient Pacific information sphere, empowering the government, media and people of Fiji and other Pacific nations to make an educated decision on what is, and isn’t, disinformation.