Climate risks that are interconnected, multiplying and intensifying can cascade across natural and human systems. Tipping points or thresholds—at which a small change can trigger a move from one state to a different state far less conducive to human survival and prosperity—may trigger unforeseen chains of events.

This requires a systems approach to understand them. Yet apart from the 2022 Office of National Intelligence climate-security risk assessment—which is classified and apparently sidelined—there is no sign this understanding is permeating the Australian government’s work. In the Defence Strategic Review and the National Defence Strategy, for example, climate has been reduced to a cameo role, just visible in a far corner of the supposedly much bigger geopolitical screen.

Given that surveys of global leaders by organisations such as the World Economic Forum consistently rate climate and related impacts as the greatest global threat, it would be prudent for the government to adopt an appropriate framework for assessing these risks in line with risk-management best practices, taking into account the full range of outcomes, including tipping points. This would include a focus on the ‘fat-tail’ risks and the plausible worst-case scenarios, including the actuarial ‘risk of ruin’, especially when the damages are so great that there is no second chance to learn from our mistakes.

These requirements and the systemic nature of the risk means governments must fundamentally rethink the approach to climate risk assessment and response, embracing complex risk analysis. Physical and economic climate models have fundamental limitations, so expert elicitation and scenario planning are crucial components in the analysis. The urgency of required action should explicitly be considered and articulated, with policy and project systems structured to respond at the speed required. And lack of certainty in risk assessment should not be taken as an excuse for inaction if risks are potentially catastrophic in nature.

A report released recently by the Australian Security Leaders Climate Group titled, ‘Too Hot To Handle’, underscores the urgency, highlighting a disturbing pattern of climate-security risk management failure.

For climate risk analysts, the past 12 months have been a wild ride, with extraordinary events taking place that are beyond scientific expectations—in some cases beyond model projections—and severe impacts arriving faster than was forecast for major elements of the climate system.

There is now consistent scientific evidence that the rate of warming has accelerated—from 0.2°C to 0.3°C per decade—with a good chance that 2024 will be as warm as the record-smashing 2023 at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This means that, in practical terms, the world has reached the lower end of the warming limits established by the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Accelerated warming will likely continue for decades, driven by continuing high emissions, plans by major fossil fuel producers to expand production, the declining efficiency of parts of the climate system’s natural carbon storage mechanisms, and cleaner air policies reducing the level of sulfate aerosols, which have been masking some of the warming.

The eminent climatologist and former NASA science chief James Hansen says the world will likely reach 2°C above pre-industrial levels by 2040—well ahead of the outdated projections used by Australian government agencies, which continue to advise the government and its methodologically-challenged domestic National Climate Risk Assessment (NCRA) that warming by 2050 will be in the 1.5 to 2°C range.

This is one example of the government’s failing to understand the nature of current climate risks, with important consequences for Australia’s preparedness to face and mitigate climate-related security challenges.

United States Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin—reflecting the views of many of the world’s most experienced scientists—recognises that climate risks are now existential and will result in major, irreversible harm if they are not rapidly addressed. According to mapping of potential threats, the greatest risk lies at the high-end (or ‘fat tail’) of the range of possible outcomes.

These should be given particular attention because many physical climate systems exhibit fast, non-linear change that is difficult to model or project and is often associated with tipping points.

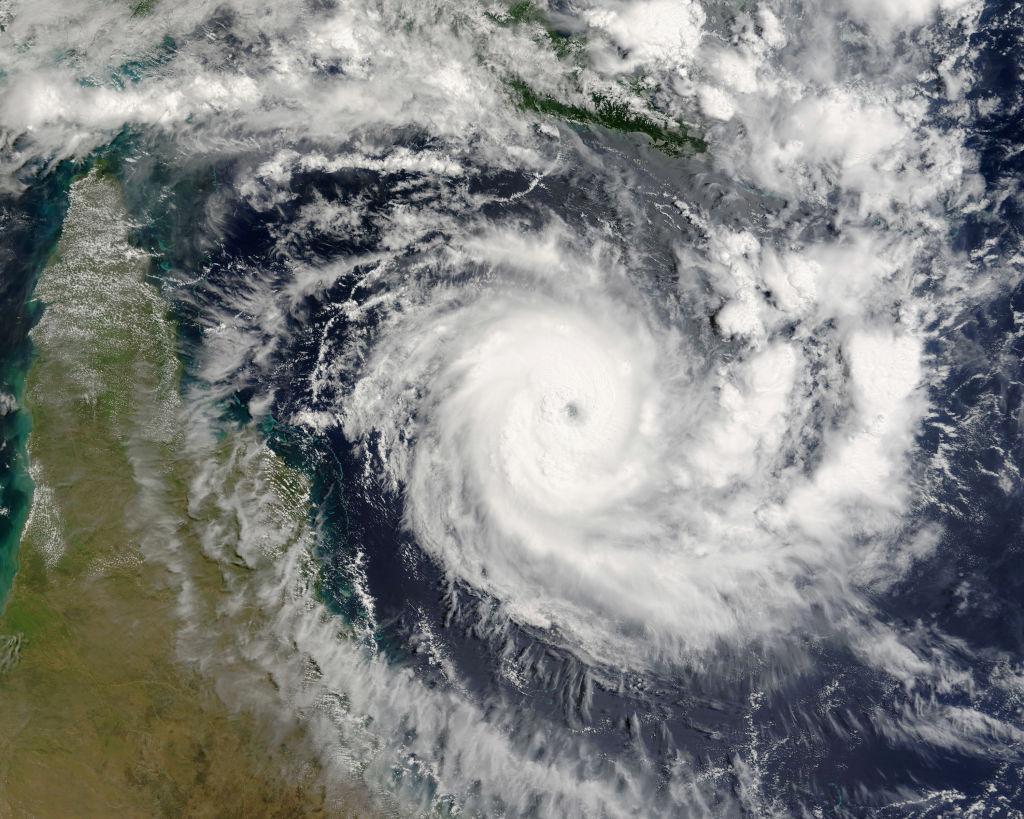

The global failure to embrace complex risk analysis as part of a basic rethink of climate assessment and response is now glaringly obvious. Scientists have described a zone of heat at 2.7°C of warming—likely to be reached about 2060 on current indications—of near-unlivable conditions, which traditionally have been experienced on only 0.8% of the world’s surface, mainly in the Sahara. That zone (as illustrated above) will include Amazonia, the region around the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, stretching to significant parts of South Asia, Southeast Asia especially Indonesia, and areas of northern Australia and Papua New Guinea. Yet by refusing to confront these implications, Australia seems hell-bent on walking into that furnace.

Once northern Australia reaches a state of near-unlivable conditions, partial depopulation is likely. The services and infrastructure on which civil society and the military depend—transport and logistics, utilities, health and social and education services for families—will degrade. Yet $22 billion has just been allocated to upgrade northern bases with barely any recognition of this reality.

The impact of this extreme heat on rice yields, wider food production, water security and the functioning of societies—as well as the potential for conflict and state failure—in many of our key Indo-Pacific partners has not been articulated, nor taken into account in any of the government’s key defence and security initiatives. We are likely building security alliances with states that will collapse.

The possible breakdown of another key global climate system is also absent from security analysis. There is a non-trivial risk that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which transports heat from the Atlantic tropics to Northern Europe, keeping that part of the world relatively warm, will collapse this century. A July 2023 study estimated a ‘collapse of the AMOC to occur around mid-century under the current scenario of future emissions’, with a high confidence (95 percent probability) that it will happen between 2025 and 2095.

This would have devastating consequences for global food production, for sea levels and for flooding in Australia. Shifts in global weather patterns would likely deprive Asia of vital monsoon rains, with enormous security consequences for the region and for Australia.

A breakdown of this system would cause temperatures to plunge in Britain, Ireland and Scandinavia, with temperatures in parts of Europe dropping by 3°C each decade and sea levels rising by a metre on both sides of the North Atlantic, while the wet and dry seasons in the Amazon would flip and severely disrupt the rainforest’s ecosystem.

Peter Ditlevsen of the University of Copenhagen says that an AMOC collapse would be a going-out-of-business scenario for European agriculture. In addition, the monsoons that typically deliver rain to West Africa and South Asia would become unreliable, and huge swaths of Europe and Russia would be devastated by drought. As much as half of the world’s viable area for growing corn and wheat could dry out. ‘In simple terms [it] would be a combined food and water security crisis on a global scale.’

Yet in the government’s analysis of climate risks, no attention has been paid to a potential AMOC collapse. It does not get a mention in the DSR or NDS, or the first pass of the NCRA. No minister or member of either major party has even mentioned it in the current term of the federal Parliament.

One of the greatest climate-related threats to our future security appears completely absent from the government’s thinking. Today’s real challenges require far broader strategic thinking than is currently evident.