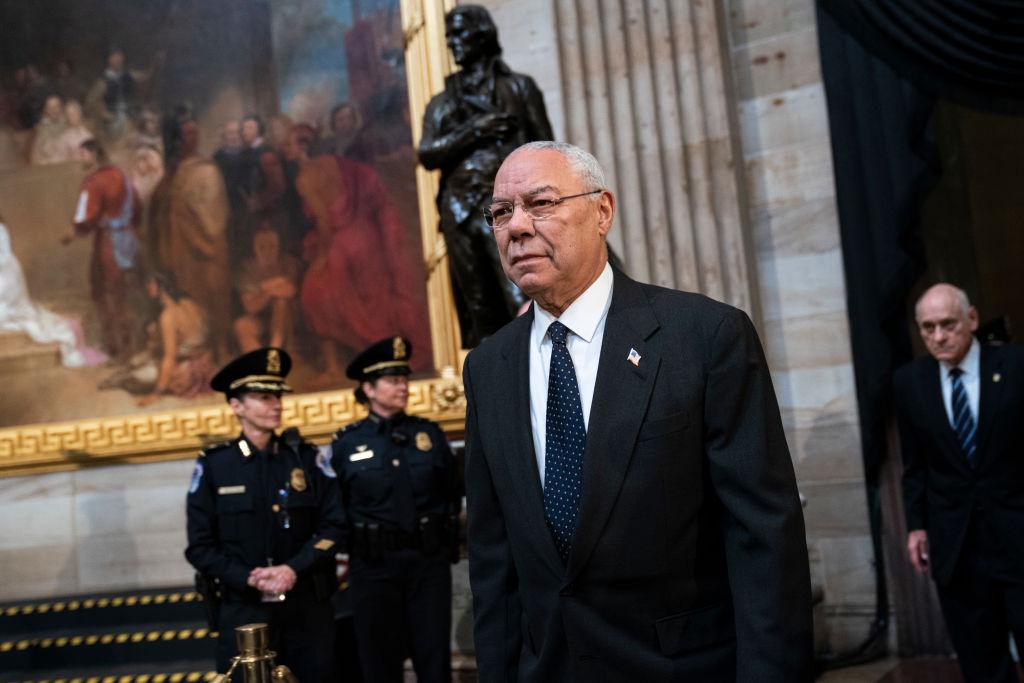

Colin Powell, former US national security adviser, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and secretary of state, who died this week at the age of 84, was a quintessential American, the son of immigrants. He was forever upbeat, someone who advised ‘not to take counsel of your fears or naysayers’ and that ‘perpetual optimism is a force multiplier’.

All of us are framed by our experiences early in life, and Powell was no exception. For him, it was the Vietnam War, where he served two tours as a young army officer. He became acutely aware of how poor policy and leadership could cost lives and destroy institutions, and came away wary of global abstractions thought up in Washington and implemented halfway around the world. With his direct military experience, war for Powell was never less than real.

Powell’s experience in Vietnam profoundly influenced his thinking as a policymaker. This was reflected in the ‘Powell doctrine’, which established criteria to be considered before military force is used. It was a plea to employ military force carefully, if at all. War for Powell was a last resort. Articulated in the aftermath of the classic, battlefield-oriented Gulf War and amid debates over less traditional interventions in the Balkans and Somalia, the Powell doctrine called for pointed questions to be asked and answered.

Are there important, clear-cut objectives that military force can best accomplish? Would likely benefits exceed expected costs? How would the initial use of military force change the situation and what would follow?

It was this last question that triggered his reference, in the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War, to the ‘Pottery Barn’ rule: if you break it, you own it. Powell understood that the measure of an intervention was not how it began but how it ended.

I worked closely with Powell when he was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and I worked for the National Security Council under President George H.W. Bush, and again when he was secretary of state and I headed his policy planning staff under President George W. Bush. (Powell also was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations for 35 years and served on its board from 2006 to 2016.) He was particularly uneasy with limited uses of force to signal to adversaries, rather than significant uses of force to overwhelm them. This led him to embrace the 1990–91 Gulf War only after the first president Bush gave him the troops and equipment he asked for. The same set of questions led Powell to advise against going on to Baghdad in 1991 and to be wary of going to war against Iraq a decade later under the second president Bush.

Did Powell always get it right? Of course not. The biggest blemish on his record was his appearance as secretary of state before the United Nations Security Council in February 2003 to make the case for military intervention in Iraq. As we now know, what Iraq’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, was hiding from international inspectors was not weapons of mass destruction but the fact that he had none.

The process that led up to Powell’s UN statement is instructive. Given a script that Vice President Dick Cheney’s office had prepared just days before, Powell insisted that the intelligence community scrutinise and validate every word. In the end, more than 90% of the initial draft was changed or eliminated. Powell made clear he would deliver only remarks informed by what the government knew and, given the inherent uncertainty of much intelligence, what it judged to be correct.

We know now the statement was in part inaccurate, owing to what is known as confirmation bias. Assuming that Saddam Hussein possessed WMD, intelligence analysts and policymakers tended to devote the most attention to information that appeared to confirm their premise and discount information that did not.

What most of the critics miss is that Powell went to great lengths to establish the truth and that what he said was what he thought to be true. One can be wrong without malign intent. Moreover, it would be misreading history to hold Powell responsible for the costly, ill-advised war that followed. Alone among George W. Bush’s senior advisers, he did not push for it, and, as subsequent events showed, Bush was prepared to go to war without much international support. At the end of the day, Powell’s efforts at the UN are not central to understanding why and how the United States went to war in 2003.

After leaving government, Powell spoke out against the illiberal drift that had come to characterise the Republican Party. He remained a man of moderation and character to the end. In this, he resembled several of his contemporaries, including Brent Scowcroft and George P. Shultz, both of whom have also recently passed away. Unfortunately for the US and the world, there are few in American public life today who can take their place.