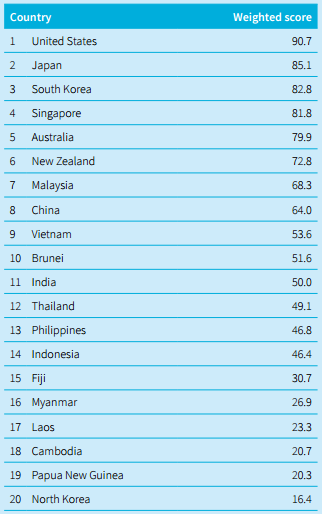

Today ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre launches the second edition of its Cyber Maturity in the Asia–Pacific 2015 Report. It analyses the cyber maturity of 20 countries, representing a wide geographical and economic cross-section of the region. For a more holistic picture of regional developments, this year’s maturity metric has expanded to incorporate five additional countries: Vietnam, Laos and Brunei in Southeast Asia; and New Zealand and Fiji in the South Pacific (see image for rankings). With these additions, this study now assesses the entire Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) grouping and seven of the ten ASEAN dialogue partners.

Today ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre launches the second edition of its Cyber Maturity in the Asia–Pacific 2015 Report. It analyses the cyber maturity of 20 countries, representing a wide geographical and economic cross-section of the region. For a more holistic picture of regional developments, this year’s maturity metric has expanded to incorporate five additional countries: Vietnam, Laos and Brunei in Southeast Asia; and New Zealand and Fiji in the South Pacific (see image for rankings). With these additions, this study now assesses the entire Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) grouping and seven of the ten ASEAN dialogue partners.

An additional layer of analysis, a standalone ‘cyber engagement scale’, is also provided. The scale is intended to be a reference tool to identify opportunities for the sharing of best practice, capacity building and development, plus commercial opportunities. Using this scale governments and the private sector can tailor engagement strategies to best fit existing levels of maturity in each policy area in each country.

Online, 2015 has been a significant year for the Asia–Pacific: the internet has played a pivotal and ongoing role in many of the region’s political disputes, economic growth spurts and social movements.

Throughout the year, awareness among regional governments of cyber threats and opportunities remains uneven. Governments that prioritise the development of coherent cyber policy frameworks understand that those frameworks are necessary for their countries to advance digitally. Others, specifically South Korea and the US, have also been subject to incidents in cyberspace that have critically affected their economic and national security. Those left behind are usually struggling to develop the required infrastructure to open up cyberspace to more of their population, challenging their capacity to develop adequate policy frameworks. However, it’s critical that those frameworks are established as cyber infrastructure is developed and not ‘bolted on’ retrospectively.

New national organisational bodies were established in 2015 and cyber issues given new ministerial prominence in several countries such as Singapore, Japan and South Korea. Governments are also taking a progressively more active role in trying to bridge the internet connectivity divide between urban and rural areas by expanding internet infrastructure, often with the support of foreign-owned private enterprise. Fixed-line and, perhaps more dramatically, mobile internet networks have expanded access to online services and markets, allowing the region’s digital economies to continue to grow.

The potential for social, economic and political change continues to expand as online technology advances and access to the internet grows. This is invigorating and enabling the next generation of technologists and entrepreneurs, but also creates avenues for new forms of crime. To reflect the increasing prominence of financial cybercrime and the need for adequate responses to it, this year’s cyber maturity metric includes a standalone assessment criterion on financial cybercrime.

Beyond domestic cyber issues, governance structures and connectivity are part of an international strategic landscape that’s continually evolving. While cyber quarrels frequently break out between various state and non-state actors, for the most part, traditional geopolitical rivalries are being replicated online, accounting for the most significant cyber incidents. This has led militaries to deepen their thinking on cyberspace, prompting to an uptick in recruiting, training and strategic planning.

The Asia–Pacific region continues to be a major source of interest for major and middle powers. Many countries are increasing their region-based capacity-building efforts. While critical to developing cyber maturity, these efforts also underpin a larger observable trend in targeted ideological persuasion and manoeuvring.

What about Australia’s position in this picture? Unfortunately, Australia has lost ground relative to progress made in Japan, South Korea and Singapore. Those countries have implemented stronger government approaches to cyber issues, and focused on invigorating innovative digital business and start-ups. Due to more rapid implementation of cyber policies in other countries, Australia’s rank has dropped from three to five, despite improving on its overall 2014 score. Strong implementation of the renewed Cyber Strategy is required to keep up with the rapidly increasing maturity of cyber policy approaches in the region.

On the plus side, Australia is a regional leader in financial cybercrime enforcement and capacity building, ranking second only to the US in the new cybercrime category. It’s highly likely that, with the implementation of the forthcoming Cyber Strategy in the coming months, 2016 will see Australia improve its ranking.

The report will be launched at a free ASPI event with special guest David Irvine AO, tonight at 5.30pm at our Barton offices. Registration and information here.