There’s a popular perception that cybercrime is an anonymous activity. With seemingly faceless attackers and ‘darknet’ sites, a picture emerges of a threat unlike anything we’ve seen before. But cybercrime shouldn’t generate this kind of paradigm shift. As Peter Grabosky astutely argued almost 20 years ago, it’s ‘old wine in new bottles’. The crime types—fraud, extortion, theft—remain the same; only the tools have changed.

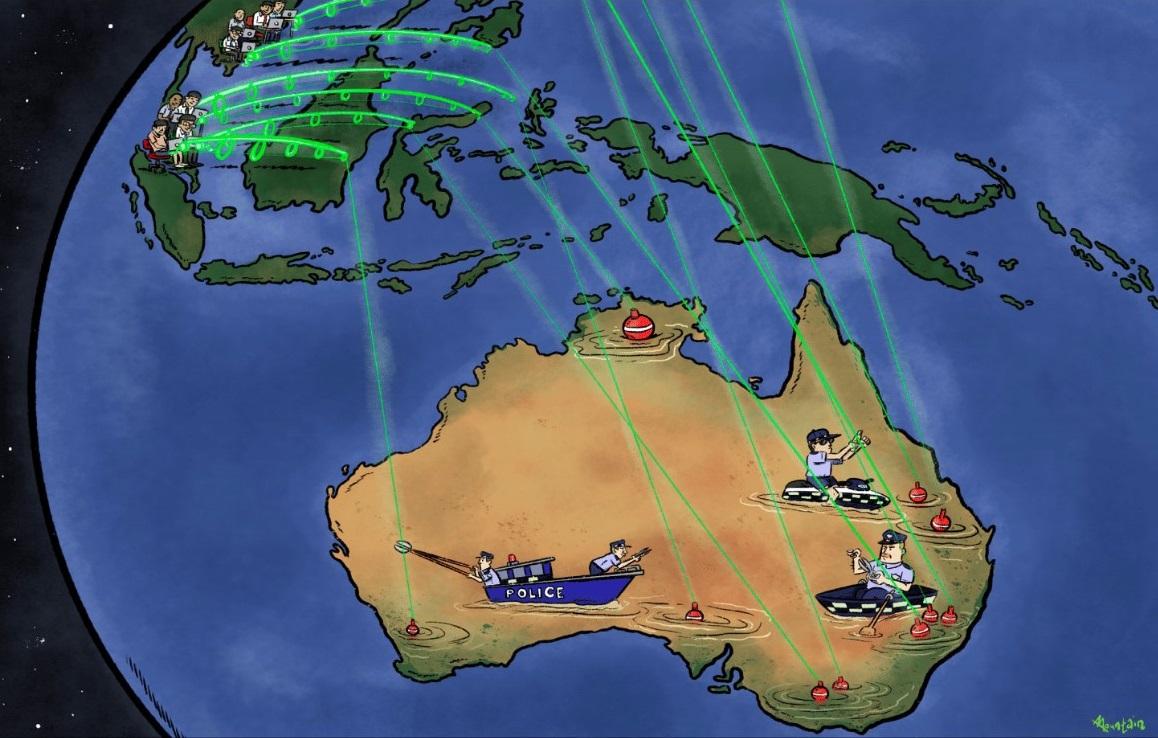

In my ASPI report, Cybercrime in Southeast Asia, released today, I argue that cybercrime is actually rooted in the conventional world. In many cases, there’s a strong offline dimension to it, along with a local one. All cyberattacks have at least one person behind them. Some of those offenders know each other. All are physically based somewhere and are the product of local socioeconomic conditions. As a result, we see different ‘flavours’ of cybercrime coming out of different parts of the world.

It’s worth quickly sketching some of the most famous cybercrime hubs around the globe. Perhaps the best known of all is parts of the former Soviet Union. That region produces the most technically capable offenders, who are often responsible for developing top-level malware and other tools that are used throughout the industry. An excellent education system produces an oversupply of able technologists who then struggle to find opportunities in a weak technology industry.

Another reputed hub is Nigeria, which is known for far less technical forms of cybercrime. Nigerian cybercriminals have traditionally carried out ‘advance fee fraud’—the email scams familiar to most of us. In more recent years, West African offenders have evolved. One growing threat is business email compromise, in which a scammer impersonates a CEO or other person to instruct an employee in the victim company to transfer funds into an account controlled by the criminals.

But there are cybercrime hotspots emerging elsewhere, including in Australia’s strategic backyard. Southeast Asia provides an interesting cybercrime case study, as it includes populations of both local and foreign offenders. While offenders are spread across the region, certain countries contain a larger cybercriminal threat than others. Vietnam, for example, hosts a local community of ‘black hat’ hackers. While some cybercriminals strike at home, Vietnam itself is not a target-rich environment and major attacks there are not widely reported. One rare example was the Vietcombank case of 2016, in which 500 million dong (A$33,000) was extracted from a customer’s account.

For those Vietnamese attacking targets overseas, credit card fraud has been a popular endeavour. The conventional business model has been to target ecommerce sites and steal their databases of credit card details. The cybercriminals can then sell the card data in virtual marketplaces or buy products online themselves and arrange for them to be shipped back to Vietnam. Vietnamese cybercriminals have also engaged in personal data theft, compromising email and other account credentials, and a number of other schemes.

If the example of Vietnam is about local offenders striking internationally, the case of Malaysia is about foreign cybercriminals using that country as a base of operations. There is a community of local Malaysian cybercriminals, but the more pressing issue is the large presence of Nigerian fraudsters who have established themselves there.

While Nigerian email scams are well known, many assume that the offenders are based in West Africa. And while there are indeed a number of offenders operating out of Nigeria, there are also Nigerian cybercriminals spread out across Africa and the world, including in the US, the UK, the Netherlands, India, the Philippines and Australia. Their presence in such countries can be for computing training, coordinating money-mule and other support operations, or running their own autonomous scam operations from those countries.

Curiously, for some time Malaysia has hosted one of the largest concentrations of Nigerian fraudsters. It isn’t yet clear why this is such a fertile location, but it’s of growing concern, as perhaps many thousands of such offenders are running hugely profitable enterprises there.

Australia’s approach to fighting cybercrime needs to be augmented to account more seriously for this local dimension, particularly in Southeast Asia, and our fight against cybercrime should be more targeted, enduring and forward-looking.

While it makes sense to continue supporting international cooperation in the fight against cybercrime, those efforts need to be targeted to specific hotspots where the problem is the most acute and Australia’s contributions can provide the greatest value for money. This involves the identification of current or future cybercriminal hotspots in Australia’s near region.

Australia’s law enforcement capacity-building programs should be matched specifically to those countries producing the biggest cybercrime threat. Deeper relationships should also be developed between investigators in Australia and in those countries through expanded use of cyber liaison posts and exchange programs.

Finally, Australia should adopt prevention programs that seek to block offenders’ pathways into cybercrime and promote those programs in cybercrime hotspots in the region.