The Australian government’s 2020 cybersecurity strategy included a headline figure of $1.67 billion in funding. This is significant, but spread over 10 years it’s certainly not going to solve the problem on its own. As the strategy makes clear, effective cybersecurity for the nation will depend on businesses as well as governments taking action. After all, it’s surely reasonable to expect that the products and services we buy are appropriately secured by the businesses that provide them.

As I describe in my new ASPI report, Working smarter, not harder, released today, the problem is that the information and communications technology market, right now, doesn’t seem to provide the right incentives to suppliers. No one buys telecommunications services based on security, and how many consumers even think about the security options provided by their internet-connected doorbell?

We have a long way to go before reaching an environment like the car market, where buyers routinely ask about the safety ratings of products and factor that information into their buying decisions. Regulation is one option to address this gap, and the 2020 cyber strategy foreshadows a role for that. Regulatory approaches can create cost and complexity, and they need to be done carefully to avoid introducing a ‘moral hazard’ by appearing to take responsibility for decision-making away from the private sector and creating the perception that government is responsible for any residual risk.

While there is a role for regulation, and it will be interesting to see the response to the discussion paper on obligations for critical national infrastructure providers as a starting point, we should also consider other options for how the government can influence the market.

The government is a major buyer of ICT, and could use its significant market power to address some of these challenges. The more than $10 billion the government spends annually on ICT procurement dwarfs any specific cybersecurity budgets, so leveraging even a small portion of it could have a major impact. Of course, the priority should be to ensure security for the direct purposes of the procurement. But the government should consider the opportunity to leverage its market power to provide for broader benefits to the Australian economy and society.

Setting the security standards expected from its suppliers may help to lift them across the board. Companies will be incentivised to lift their standards in order to qualify to do business with the government, and it will often be easier for them to apply those standards across their whole enterprises rather than just for government contracts.

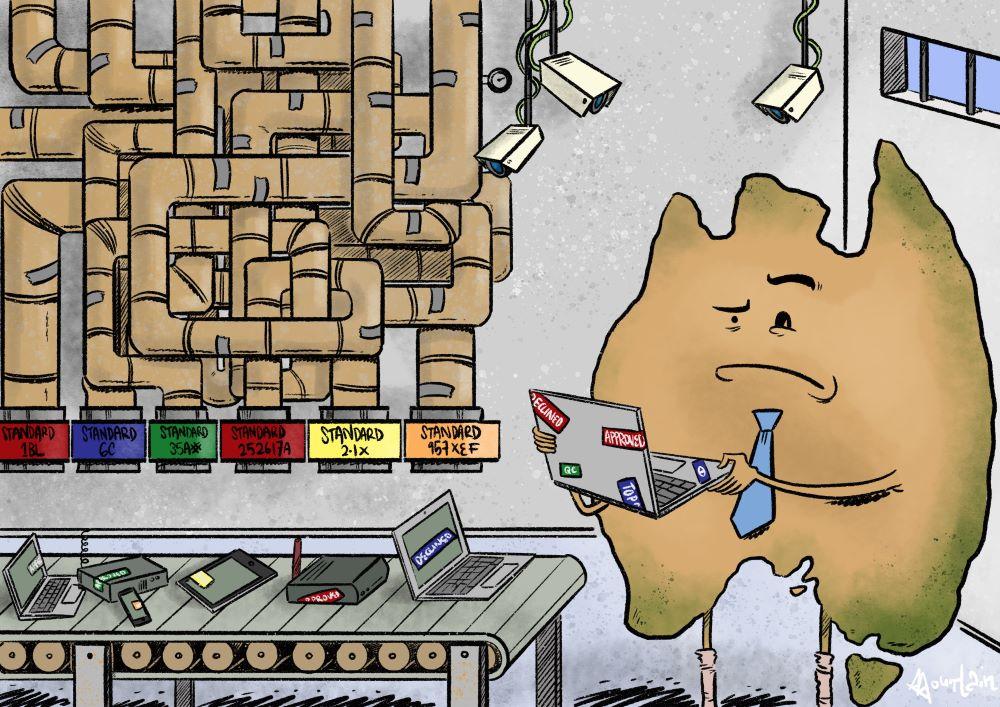

Many cybersecurity practitioners, however, will tell you the problem is not a lack of standards, but too many of them, and we found that open, published tenders have a wide range of levels and types of security requirements levied on them. The key is to come up with common standards that are scalable and also provide a series of levels of maturity. All suppliers could gain recognition at the basic level, for example, but those that want to differentiate themselves can get up to the equivalent of the 5-star ANCAP safety rating that the best car manufacturers have.

Government procurement also needs to be flexible enough to allow innovative security approaches to be recognised and encouraged. Commonwealth procurement rules require departments and agencies to ensure value for money, but all too often this is interpreted as ‘cheapest minimally compliant solution’. This means that if providers believe they have differentiating security capabilities, their only realistic route is to lobby buyers before tender documents are drafted to get their preferred requirements included in the specification (something that may be possible for large, established companies, but isn’t feasible for many small, innovative businesses in the sector).

A better option would be a mechanism that mandates that security always be explicitly included in the evaluation. One approach would be to make security a ‘fourth pillar’ in evaluating proposals, alongside cost, quality and timescales, although that then leaves room for subjectivity about how to measure security and weigh it against the other criteria.

The ideal approach would be an effective pricing mechanism, reflecting the fact that better security should equate to lower financial risk. We understand that governments have been looking at how to value cybersecurity risk and have found it challenging, so little progress has been made on this to date.

It may be that we can learn from a well-established market that provides a mechanism for consolidating data, sharing risk and best practices, helping organisations manage and reduce risk, and putting a price on residual risk—the insurance industry. Today, the market for cybersecurity insurance, particularly in Australia, is poorly developed.

We should think about introducing mandatory cyber insurance for government suppliers, a move that could help kick-start the industry and build the critical mass it needs. Cyber insurance obligations would be similar to existing ones for mandatory public liability insurance that are commonly found in government tender requirements. Insurers would, over time, provide lower premiums to suppliers that reduce risk, just as they do with public liability by incentivising construction companies to improve site safety, for example. If we ensure that such insurance not only covers liability for security breaches, but also includes resources for incident response and resilience, it would provide assurance that all suppliers will have access to these resources when required.

Of course, there will be challenges in implementing these ideas, but we need an integrated approach that considers how the government’s ICT procurement can be leveraged to support its new cybersecurity strategy. Doing so will improve the security of the government’s ICT systems, raise security standards across the board and ensure the government’s spending on cybersecurity has the maximum possible impact.