Last week was a bloody week for Indonesia. First there was a prison riot on 8 May at the command headquarters of the Indonesian police’s Mobile Brigade (Brimob), where over a hundred convicted terrorists held a 36-hour standoff. The riot left five officers and one prisoner dead. The next day, another police officer was stabbed to death in the same area by an alleged terrorist.

The worst happened on Sunday morning. Suicide bombers attacked three separate churches in Surabaya, Indonesia’s second largest city. The police claimed that the perpetrators were a single family (both parents and their four children). Police chief Tito Karnavian noted that the husband was the Surabaya cell leader of Jemaah Ansharud Daulah (JAD), an Islamic State (IS)‑linked group that the US has deemed a ‘specially designated global terrorist’. There were more than a dozen fatalities, and more than 40 injured.

Earlier in the day, the police shot and killed four suspected terrorists in Cianjur, West Java, who were planning another assault against the Brimob headquarters. But hours after the Surabaya attack, several bombs exploded in Sidoarjo, a regency on the outskirts of Surabaya, killing three people, including the suspected terrorist’s wife and child. Finally, on Monday morning, suspected terrorists detonated explosives outside the Surabaya police headquarters, wounding six civilians and four officers.

So, just within 25 hours in East Java, the attacks left at least 28 fatalities and 51 injured, making it the deadliest series of attacks in over a decade. As more details emerge in the coming days and weeks, we’ll have a better sense of what happened. But for now, let me offer some preliminary thoughts.

First, the events over the past week represent a serious and dangerous escalation of IS‑linked attacks inside Indonesia. We haven’t seen a simultaneous, coordinated church bombing since the 2000 Christmas Eve bombings that killed more than a dozen people across eight cities. We also rarely see a series of continuous and coordinated terror attacks by terror groups that span nearly a week, perhaps more. The attacks also marked the first successful attack by female suicide bomber in Indonesia.

If it’s established that IS‑linked groups in Indonesia such as JAD are capable of planning and executing multiple and coordinated attacks for stretches of time, there’s ground for concern.

Analysts have long warned that even as the terror threat in Poso was winding down and Jemaah Islamiyah continued to lay low, IS‑linked groups like JAD and returnees from Syria and Iraq pose a growing new threat in Indonesia. The JAD bombers in Surabaya were alleged to have just returned from Syria. The police claims that there are over 500 returnees from Syria or Iraq in Indonesia—although some had estimated that approximately 700–800 Indonesians went to those two countries between 2013 and 2017.

Second, one of the key challenges when it comes to Syria–Iraq returnees is the absence of a more comprehensive and powerful law to deal with them. According to the police, until those returnees commit a ‘concrete act’ of terrorism, they cannot be arrested. They haven’t broken any laws simply because they ‘fought’ in Syria or Iraq. The police have also complained about the lack of detention power and authority over suspected terrorists—and therefore their lack of ‘preventive’ capabilities.

Following the January 2016 attacks in Jakarta, the Indonesian national legislature began debating a revision to the 2003 anti-terrorism law currently in place. The debate continues, and centres on a wide range of contentious issues, from ‘defining’ terrorism to the role of the military, the lack of specificity in terror offences and the expansion of detention powers.

Following the Surabaya attacks, Indonesian President Joko Widodo gave an ultimatum to the national legislature, saying that if it can’t pass a new anti-terror law by June, he’ll issue an anti-terror Government Regulation in Lieu of Law (PERPPU) of his own. It’s unclear how the PERPPU would address those contentious issues now being debated by the legislature.

Third, a new counter-terrorism law—while a step in the right direction—isn’t a panacea for Indonesia’s broader terror landscape. For one thing, despite the narrative that the IS‑linked threat is global in nature, domestic challenges continue to shape Indonesia’s terror landscape.

As one recent study carefully noted, Indonesians aren’t lured into joining ISIS simply because of its ideology or propaganda. Instead, the study argues that local political and religious dynamics are central issues. These include, among others, the pre-existing debates over the role of Islam in public and private life; the lack of restrictions and uneven implementation of legislation on social, political, and religious organisations; and the intra-jihadi community competition whereby IS affiliation is used to bolster the credentials and agendas of some clerics and personalities.

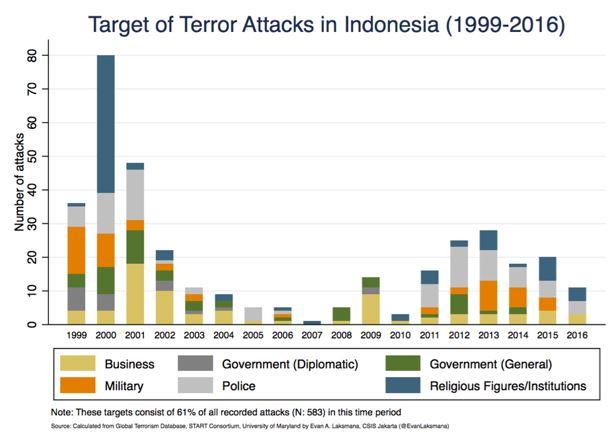

In addition, the nature of the attacks over the past week should be viewed within the broader trajectory of terror attacks in Indonesia over the past decade. As the following chart shows, religious figures and institutions haven’t been targeted to the same degree that the police have been over the past decade. But recently, religious figures and institutions have again become more prominent targets. The Surabaya attacks fit within the pattern that seems bent on exacerbating pre-existing religious cleavages and tensions.

Indonesia can and should do more to address the growing and increasingly lethal IS‑linked threats. But the upcoming debates over the best strategies and solutions, including a possible new anti-terror law, should be conducted with a level-headedness that considers the broader and long-term terror landscape.

One shouldn’t rush into abandoning the current criminal justice model of counterterrorism in return for a more repressive, or ‘war-fighting’, one. As Indonesia’s own long history tells us, repressive measures often lead to prolonged and more deadly conflicts in the future.