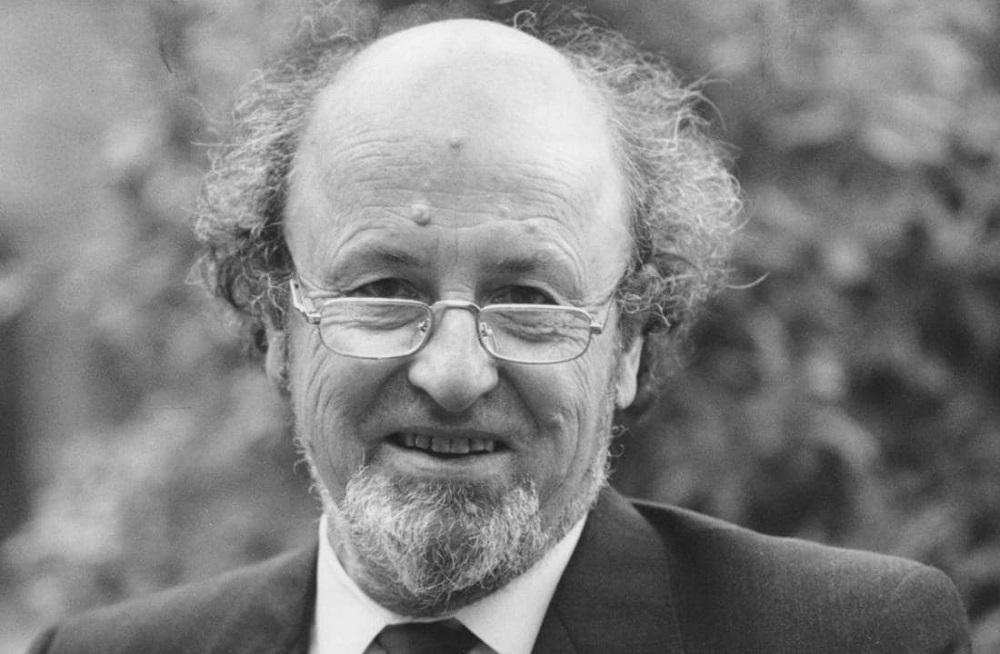

The former Treasury deputy secretary and member of ASPI’s inaugural council Des Moore sadly passed away in Melbourne on 1 November at the age of 88. As David Uren noted in his tribute published in The Australian, Des was a feisty public policy pugilist, deeply committed to the case for smaller government, lower taxes and economic deregulation.

Des sat on the ASPI council from its inaugural meeting in August 2001 through to his retirement as a councillor in August 2007. He was appointed to the council by Defence Minister Peter Reith, and I recall a later discussion with one of Reith’s chiefs of staff who was relishing Des’s appointment. ‘He’ll keep the council on its toes’, was the assessment.

Des was a passionate advocate of the American alliance and of the need for strong defence capabilities, and this became a theme in his interaction with ASPI staff and fellow councillors. In the early days of ASPI there was a debate about what ‘independence’ really meant in terms of the research and public commentary staff could undertake. Des firmly held to the view that the council should have a hand in editorial direction.

Robert O’Neill, ASPI’s inaugural chair, maintained that ASPI’s executive director and staff should have the latitude to express their own views. O’Neill’s stance was the correct one in my view and helped to set the foundations for the type of organisation ASPI is today. But there’s a lot to be said for strong views consistently and plainly put, and Des was a master of that art. He helped shape the institute in its early days and reminded us all that policy judgements profoundly matter and need to be explained, advocated and defended in a tough marketplace of ideas.

After his time on the ASPI council, Des kept an active interest in defence and international security issues. He would regularly send his thoughts on interesting developments to an email contact group, addressing, among other things, the fight against Islamic State, his ‘amazement at the policy on submarines’, China, climate and the political battles of the day. His interest in policy issues ran deep and was sustained through all his life.

I last saw Des at our June 2019 conference on ‘War in 2025’. At that point, walking with a cane, he attended every conference session and asked the chief of the Australian Defence Force a pointed question about climate change (Des was emphatically not a believer). Des emailed me after the conference saying he found it ‘most helpful’ and asked for speech transcripts for his further study.

A decade and a half ago, I recall an ASPI council event at which a respected agency head had given a talk on national security which had much been to Des’s liking. He asked the agency head with some incredulity, ‘So you say you have had a long career in DFAT?’ It seemed unlikely to Des that one could have that background and still say sensible things on security. Spirited, opiniated and at times a bit of a curmudgeon, Des Moore was a believer in public policy and the need to vigorously engage in the contest of ideas. He never lost that spark.

David Uren noted that Moore’s vigorous voice had been heard on one side of every public economic policy debate in Australia for the past 35 years.

Moore spent three decades in Treasury during a period of great intellectual ferment about the scope and nature of economic policy, before making the transition from public service to public intellectual in the late 1980s.

His Treasury career was associated with John Stone, who was the department’s formidable secretary from 1979 to 1984. Stone had been Treasury’s representative in London in the late 1950s when Moore, who was studying at the London School of Economics, paid him a visit, which eventually resulted in a job offer.

Stone recalls that Moore came from a wealthy Melbourne retailing family and might have been expected to return from his London studies to pursue a profitable career in business, but instead chose to take on a low-paid position at Treasury.

‘Des was never interested in his own wealth, but was a passionate believer in public policy and the public interest’, he said.

Treasury was an institution of extraordinary power and influence in the 1960s and 1970s, carrying sole responsibility for all Australia’s foreign borrowing, overseeing the exchange rate and taking charge of the budget, which was the main instrument of economic policy. Monetary policy and central banking were much less important in those days.

Through the 1970s, there were big debates within Treasury about the place of government spending, the role of money supply, the regulation of financial markets and the cost of Australia’s wall of tariff protection. The department’s culture was to foster robust debates internally but present a united face to the outside world.

Treasury was appalled by what it saw as the spendthrift ways of Gough Whitlam’s government. Whitlam blamed Moore and Stone for what he believed was Treasury obstruction. Treasury also found itself at loggerheads with the subsequent government of Malcolm Fraser. Moore was at the centre of debates between Treasury and Fraser over devaluing the currency.

As Treasury deputy secretary through the early 1980s, Moore was involved in implementing the early reforms during Paul Keating’s time as treasurer, but he left the department in 1987, concerned the government’s economic settings were too expansionary. Stone left in 1984, replaced as secretary by Bernie Fraser.

Moore then threw himself into the realm of public policy, heading the economic policy unit at the libertarian Institute of Public Affairs, and then establishing a one-person think tank, the Institute for Private Enterprise, with a newsletter presenting the case for smaller government, lower taxes and deregulation of the economy.

He was active in the H.R. Nicholls Society lobbying for industrial relations deregulation and was also involved in the formation of ASPI.

Over the past decade, the climate change debate became a passion, as he argued there was not the statistical evidence to support the thesis of human-induced global warming.

Moore was a keen supporter of the arts, reflecting the engagements of his wife, Felicity. They could always be found close to the front row of the Australian concerts given by their daughter, Lisa, who is a renowned US-based performer of contemporary piano. He also leaves behind two sons.