Discussions during a trilogy of AUKUS-related events in Washington on the one-year anniversary of the deal’s announcement suggest the novel strategic partnership is about much more than submarines, the transfer of nuclear propulsion know-how and Anglosphere chumminess.

Political officials, scholars and practitioners gathered last week under the auspices of ASPI, the Center for New American Security and the Centre for Grand Strategy at King’s College London to identify key successes and primary challenges for the partnership.

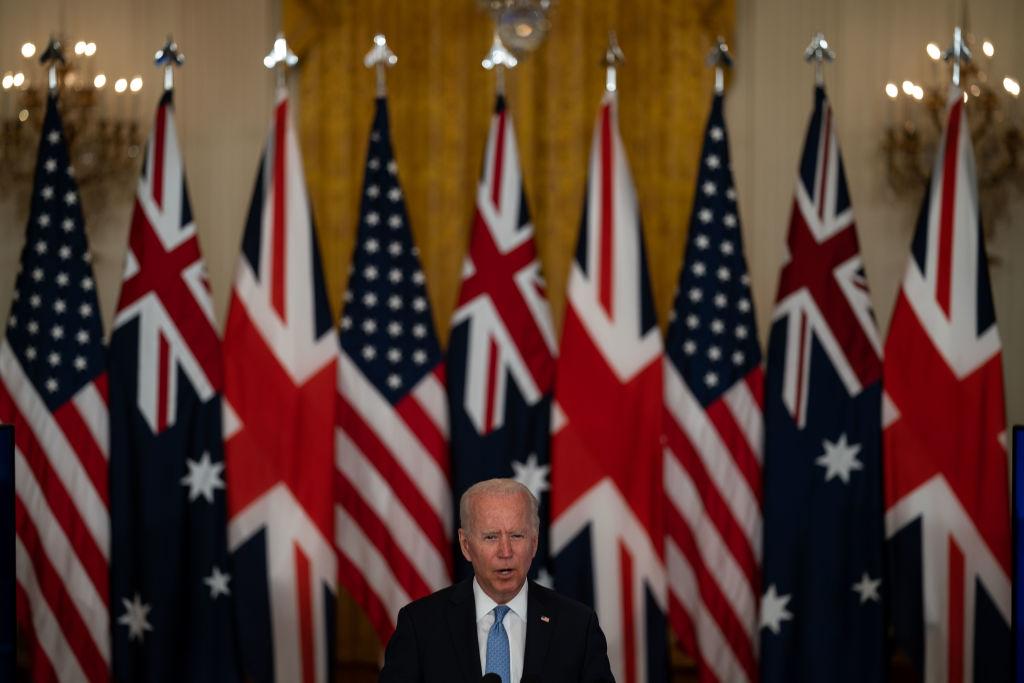

The political leadership in all three countries appears fully aboard with AUKUS—the deal has survived a change in government in Australia and a change in prime minister in the UK—and officials describe levels of cooperation not seen since World War II to streamline advanced technology sharing. Participating officials described AUKUS as a new paradigm of defence integration across a broad spectrum of advanced technologies to maintain scientific and engineering advantages while improving a collective defence posture among the three countries.

For the US, this project represents an overdue shift of attention to the Indo-Pacific and a determined effort to make good on longstanding promises of a geostrategic pivot to the region and the looming Chinese threat with the help of steadfast partners. It also portends a change in the American approach to alliance capability sharing. AUKUS helps to further anchor Australia in the American defence orbit and should make Beijing think hard about how to respond to a Canberra that’s increasingly willing to push back against Chinese aggression. In the UK, the AUKUS agreement is seen as necessary to show strength alongside allies with shared interests and values, but also as part of the UK’s new ‘global Britain’ strategy in the wake of its departure from the EU.

The much-publicised submarine component of the pact—so-called pillar 1—appears to be moving forward apace. All parties expect that a plan to provide Australia with nuclear-propelled submarines will be announced, as scheduled, in March. The details are being held close by officials, but a year into talks, confidence is growing that delivery may occur earlier than the parties expected at the beginning of discussions. Besides the actual capacity-enhancing propulsion technology transfer, AUKUS partners see pillar 1 as a ‘big bet’ signal that will demonstrate a capacity to meet the defence coordination challenges of the second pillar, relating to artificial intelligence, quantum computing and other emerging technologies.

The decision of the AUKUS partners to take their case for the sharing of nuclear-propulsion technology to the International Atomic Energy Agency in the interests of transparency, and the response from most of the international community to consider, accept or support the argument in good faith, portend success for pillar 1. Some allies and partners have expressed concerns about AUKUS’s effects on nuclear proliferation and possible further destabilisation of the Indo-Pacific, but the Chinese information campaign to discredit AUKUS has so far failed to gain much traction.

Despite widespread support for AUKUS and a desire for its success, three pressing issues were repeatedly raised throughout the discussions.

First, there is a lack of clarity around AUKUS’s strategic purpose and what each partner aims to achieve. The inability to define specific, shared goals beyond banalities of protecting the ‘rules-based order’ or technology sharing to ‘deter Chinese aggression’ may belie a failure to identify different threat perceptions and risk appetites, which, if accounted for, help determine how to rank the technologies that are critical to advancing specific interests for each partner.

Does AUKUS strengthen integrated deterrence against a common threat, namely China, or may some technology transfers—even discussion of them—trigger escalation in some scenarios? If power projection is itself a goal for one or more of the partners, pillar 2 activities need tailoring. It is understandable that more time is needed here given that the efforts under pillar 1 are the initial priority. Determining metrics for measuring AUKUS’s worth is necessary before making any further claims of success, however.

Second, the story of AUKUS—or lack of one—also poses a challenge. The narrative on the need for the deal in the first place hasn’t really registered beyond nuclear submarines meeting Australia’s defence needs, resulting in confusion from regional allies and partners, and giving rise to concerns that AUKUS could destabilise the Indo-Pacific region. Canberra, London and Washington need to have explicit and uncomplicated discussions with allies and partners about what they intend the deal to accomplish more broadly.

Is AUKUS a trial run for a similar, future initiative with Japan, France or other countries in the Indo-Pacific? The potential for Chinese disinformation to colour perceptions of the deal will grow the longer that the AUKUS members delay announcements and fail to fully explain its parameters and objectives. This effort will require the AUKUS partners to gain a more comprehensive understanding of why allies and friends may be sceptical, regardless of Chinese influence.

Finally, a major concern is the failure so far of AUKUS partners to assess the role of commercial industry, supply chains and broader society in enabling pillar 2 to succeed. Shared bureaucratic, legal and practical infrastructure is needed to support sustained advanced technology sharing across myriad critical technologies—all of which are at various stages of development. Each partner needs to conduct a comprehensive review of its supply chains and skills gaps to ensure shared technology is utilised and retained.

Pillar 2 is fundamentally different from pillar 1. A top-down approach needs grassroots support for AUKUS to succeed. Pillar 2 exceeds the scope of traditional defence capability sharing, and this alone will necessitate creative and uncomfortable changes at all levels to ensure its success. Long-term momentum may be difficult to sustain without greater industry and civil-society stakes in AUKUS’s development and a better understanding of its potential benefits. Domestic diplomacy will need the support of think tanks, educational institutions and ‘track 2’ planning to clarify and refine AUKUS over time.