In March 2017, the Minister for Defence Industry told ABC radio that ‘We know the defence industry is driving the economy.’ He backed up that claim by referring to the just-released National Accounts for the December quarter, saying, ‘it showed that defence spending had increased by 15.2 per cent over the year and 34 per cent in that quarter alone and was showing up as a major reason for the increase in growth’.

Of course, defence spending hasn’t increased by anything like either of those figures. What’s probably happened is that one of his staff noticed the line in the ABS release that says, ‘public investment increased 7.7% during the quarter driven by Defence (34.2%) and….’.

The statisticians weren’t talking about defence spending, but rather the impact of defence investment on ‘fixed capital formation’. Checking through the ABS spreadsheets, it turns out that defence fixed capital formation for the December quarter was 15.1% higher than the corresponding figure a year before. So, almost certainly, the Minister was referring to defence fixed capital formation.

Now if you take defence-related fixed capital formation to be a proxy for Australian defence industry (I’ll explain later why it’s not) the Minister’s claim begins to make sense. Crunching the numbers, defence-related fixed capital formation contributed 0.15% to the quarterly GDP growth of 1.1%. But that doesn’t mean that defence industry was ‘a major reason for the increase in [economic] growth’. To understand why, we need to look at how GDP is calculated in the National Accounts:

GDP = Final Consumption Expenditure + Gross Fixed Capital Formation + Exports of goods and services – Imports of goods and services

Final Consumption Expenditure is the value of what’s purchased for consumption (food, clothing, medical services, etc.). Gross Fixed Capital Formation is the value asset purchases (building, railways, fighter aircraft, etc.).

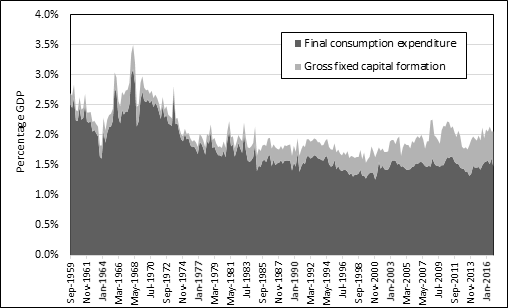

The ABS provide figures for defence final consumption and fixed capital formation (but not for exports and imports). Figure 1 shows the results going back to 1959, seasonally adjusted. Not surprisingly, the total mirrors the share of GDP spent by the government on defence. Defence final consumption is large because it includes personnel costs, as well as items such as rations, fuel, uniforms, and equipment maintenance.

Figure 1: Defence related contributions to GDP in the national accounts, 1959–2016

Note also that fixed capital formation has been growing as a share of GDP since at least the early 1970s. Fixed capital formation includes the construction of defence facilities and the purchase of new equipment. It’s been growing because (1) increases to the price of military equipment have outpaced inflation, and (2) the ADF has been becoming more capital intensive (including through the post-2000 defence build-up).

So far, no surprises: you spend a couple of percent of GDP on defence and it shows up as a couple of percent of GDP in the National Accounts. You’d worry if that weren’t the case.

But what about defence industry ‘driving the economy’. There are two problems with Minister’s statement.

First, the quarterly figures for defence fixed capital formation are too volatile to deduce anything from either a quarterly or annual quarter-to-quarter figure. The figures for the past eight quarters (working backwards) were: 34.2%, -28.6%, 30.0%, -7.4%, 32.2%, -35.3%, 29.6% and -5.1%. You can’t sensibly extract a trend from such volatile data over a brief time—it’s like looking for evidence of global warming by comparing today’s temperature with yesterday’s.

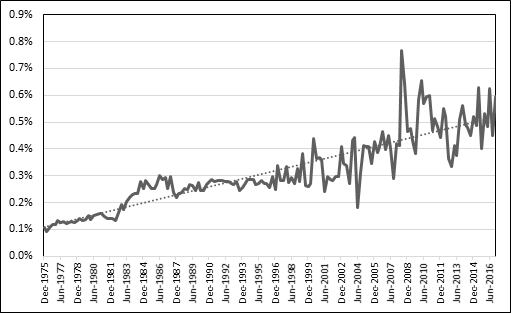

If you want to understand the economic importance of defence fixed capital, it’s the long-term share of GDP that matters. On that basis, shown in the Figure 2, there’s no short-term trend to be seen, and the long-term trend is an increase of a mere one-hundredth of a one-percent of GDP per annum.

Figure 2: Defence-related fixed capital formation as a share of GDP, 1959 to 2016

Second, as already mentioned, defence-related fixed capital formation is a poor proxy for defence industry. To start with, it includes the value of imported defence equipment (which is why the equation for GDP subtracts imports). It’s entirely possible that the 34.2% jump referred to by the Minister came from a surge in defence imports. In recent years, less than 40% of Defence’s procurement budget has been spent in Australia. Once that’s considered, the 0.5% of GDP attributed to defence fixed capital formation falls to 0.2% of GDP. And, yes, defence exports add a further boost, but it’s too small to worry about in the national accounts. In addition, defence-related fixed capital formation includes facilities construction, which is both substantial ($1.5 billion this year) and entirely unrelated to defence industry.

A focus on fixed capital formation also ignores the substantial contribution that defence industry makes to sustaining ADF capabilities. Materiel sustainment resulted in around $4 billion of local expenditure in 2015–16, compared to only $2.4 billion on equipment purchases. But the money spent on local sustainment was always going to happen, irrespective of the government’s ‘buy Australian’ defence procurement policy. The tyranny of distance means there’s usually no practical alternative to supporting defence assets locally.

To recap, far from ‘driving the economy’, defence industry contributes modestly to the national accounts. That’s to be expected; the National Accounts are roughly a case of what you put in, you get out. Moreover, the quoted growth of 34% in fixed capital formation comes from data that’s far too volatile to sensibly extract short-term trends—even if that weren’t the case, defence-related fixed capital formation is a decidedly poor proxy for defence industry.

With so much emphasis on generating jobs and growth from defence production, you’d think that the government would be getting the best economic analysis available to guide its decisions. Yet, as this example shows, that’s not the case. I wonder whether the economic analysis underpinning the looming wave of ‘nation building’ defence mega-projects is any better.

This is an extract from the forthcoming ASPI Defence Budget Brief.