In his recent article, ‘Pivoting back north’, Allan Dale argues that reforms are needed to pave the way for progress in northern Australia. Reflecting on the challenges of the northern Australia development agenda since the 2015 white paper, Dale says that ‘on-the-ground economic and social benefits have been slow to materialise’.

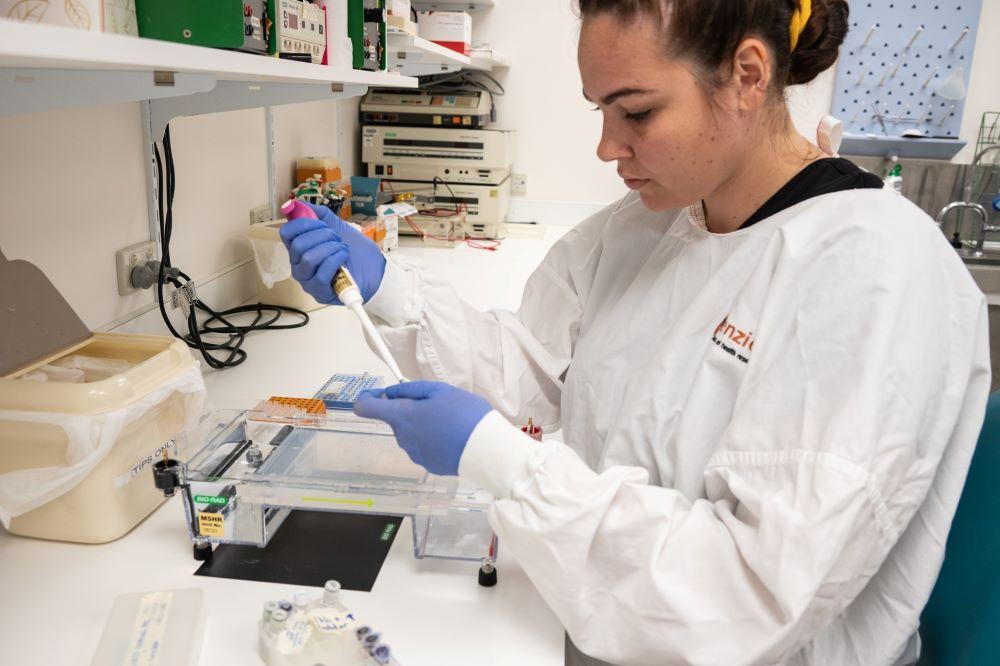

Yet, notwithstanding the difficulties encountered by some large infrastructure projects, many of the investments framed by the 2015 white paper have had demonstrable social impacts in the north’s regional and remote communities and beyond. Investments in tropical disease research and health security have strengthened the region’s capacity for policy-relevant research with partners in the Asia–Pacific. Funding for northern-led research has improved researcher retention and recruitment, researcher–practitioner collaboration and knowledge transfer. Health service delivery has improved through initiatives to empower local services and communities in place-based healthcare planning.

These investments were enabled by the inclusion of health in the white paper. The document recognised the potential for health and medical research organisations across northern Australia to strengthen their role as international leaders, particularly in tropical health and medicine. Tropical health became one of three pillars of the $75 million Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia, alongside agriculture and food, and later Indigenous-led business development.

Even so, health has taken a back seat in the debate over the sustainable development of the north. Conceptions of health as a priority investment area—to the extent they exist—tend to lack a clear definition and fail to articulate the link between economic development and healthy communities.

The World Health Organization defines ‘health’ as not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, but a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing. Health underpins the peace, security and prosperity of communities and nations.

Remote northern Australia has among the highest rates of preventable deaths and potentially preventable hospitalisations in the country. Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in the north have among the highest reported rates of youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the world. With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples comprising 16% of northern Australia’s population, and many living in remote areas, health must be central to the region’s development, with an emphasis on the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community.

A healthy population underpins economic development, including innovation across a range of industries such as agriculture, defence, health services and medical technologies. Health and social assistance is one of northern Australia’s largest employing industries. With the north’s proximity to the Indo-Pacific and tropical climate, health security is also pivotal, as is the imperative to respond to endemic tropical diseases that could impede prosperity.

The federal government’s commitment in the 2023–24 budget to a refresh of the 2015 white paper recognises this. The stated priorities include ‘strengthening First Nations engagement for advancement and focusing on climate action’ and enhancing ‘liveability and prosperity’ in the north. To deliver on these priorities, investment is needed in four key health-related areas: service delivery, cross-sectoral collaboration, international engagement, and research and evaluation.

First is service delivery. A 2020 situational analysis of health service delivery in northern Australia noted several strengths, such as the innovative service models led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled health organisations that deliver culturally safe service models for comprehensive primary health care.

It also identified challenges, including health workforce shortages and high rates of turnover, along with barriers to healthcare access and poor care continuity. Services are often fragmented, with poorly coordinated financing and governance, which affects both access and quality. As findings from coronial inquests show, improving access to quality health care is an urgent priority for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Addressing the prevalence of complex chronic disease across the remote north requires comprehensive primary care and integration with specialist acute care services.

While the white paper refresh should consider broad opportunities to strengthen health service delivery, building up the region’s health workforce is pivotal. Better local training and support, tailored to local health needs and supplemented by attraction and retention strategies and improved liveability for families, are critical.

The second priority area is support for cross-sectoral approaches. Persisting inequities highlight the importance of the social, cultural, commercial and environmental determinants of health. These include housing, employment, education, healthy environments, climate change and nutrition. Culture and connection to country are also key health determinants for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The ‘one health’ approach also recognises that interconnections between people, animals and the environment shape health outcomes and responses to global health threats such as Covid-19.

Social determinants are reflected in many government policies, but there are often gaps between policy intent and implementation. Connecting sectors to improve health requires joint planning and innovative governance models that support effective co-design and collaboration. The success of the northern Australia development agenda hinges most on governance models—they must be designed to allow policy intentions to be linked with evidence and action, building on learnings from past successes and failures.

The third priority is to strengthen collaboration on shared health challenges with Australia’s regional neighbours. The government’s health security initiative for the Indo-Pacific region is funded from mid-2022 to deliver a suite of programs, and should be linked to the northern Australia development agenda. Investments like this strengthen ties and improve health outcomes while also supporting regional security.

Finally, investment in quality research that breaks new ground and integrates lessons from past and current policies and interventions will support health planning across the north. Despite recent investments, universities and research institutes in northern Australia still receive less health research investment per capita than those in the rest of the country.

Supporting the career pipelines of northern-based researchers undertaking research that responds to current and future local needs requires sustained funding and resources. Service and planning organisations also need support to lead their own research, evaluation and quality-improvement activities. Coupled with high-value investments in infrastructure, such as data platforms and training programs, this support will drive engagement with key policy initiatives such as the establishment of an Australian centre for disease control. The northern-based Research Translation Centres could play a key role in networked, cross-jurisdictional approaches to research development and policy engagement.

The eight years since the 2015 white paper have brought many important lessons. A refreshed white paper presents an opportunity to collate evidence and encourage sharing of ideas for development and reform across multiple sectors. Health must be at the centre of these efforts, not least because healthy people and communities provide the backbone of the economy and a critical platform for innovation.