Originally published 2 March 2019.

Originally published 2 March 2019.

Just over 20 years ago, a letter from Australian prime minister John Howard to the president of Indonesia, B.J. Habibie, set in motion a chain of events that would lead to East Timor’s passage to nationhood.

The ‘Howard letter’, as it has been known ever since, was a bold attempt to free Australia and Indonesia of their most burdensome bilateral problem.

It was high risk, and it failed in its stated aim: to find a way to legitimise East Timor’s incorporation within the Republic of Indonesia.

By providing the indirect trigger for Habibie’s decision to give the East Timorese an early vote on whether to separate from Indonesia, Howard’s diplomacy also bears some responsibility for how the East Timor referendum played out in an orgy of property destruction and bloodshed.

It is not possible for Howard’s government to cast itself in the role of sponsor of East Timorese independence, as some have, without accepting a certain degree of ownership of the cost for East Timor in attaining independence.

Still, the unintended consequences of Howard’s intervention were not all negative. The East Timorese were delivered their freedom. Indonesia was delivered from a long diplomatic purgatory. And what was the biggest single impediment to relations between Canberra and Jakarta was laid to rest.

So, what are the lessons and legacies of one of the most creative and ambitious episodes in Australian foreign policymaking?

With the passage of time, the impact of the Howard letter ought to be easier to assess, although the repercussions of Australian diplomacy in 1998–99 are likely to play out for many years to come.

But first some background.

Howard’s letter came at a fragile time in Indonesia. President Suharto was removed from power in May 1998 after 32 years; his demise was preceded by a collapse in the value of the rupiah, a deep recession and widespread rioting on the streets of major cities. As his successor, Habibie was left to clean up the entwined crises of economic confidence and political legitimacy.

Habibie was a restless reformer. He quickly set about overturning many of the basic tenets of Suharto’s ‘new order’, including the refusal to consider any change to the nature of Indonesia’s rule of East Timor. One of Habibie’s early acts was to offer the East Timorese a package of special autonomy.

The speed of change caught Australia off balance.

In 1979, Australia had broken with the United Nations consensus and granted de jure recognition to Indonesia’s incorporation of East Timor, a policy adopted by every successive Coalition and Labor government. In 1998, it suddenly faced the prospect of maintaining a less progressive policy than Indonesia.

The letter Howard sent on 19 December aimed to seize back the initiative. This was undoubtedly motivated in part by domestic politics. The Labor Party had started to shift ground, backing an act of self-determination for the first time. Australia’s pragmatic accommodation of Indonesia over East Timor was never popular and becoming less so.

It left the Howard government searching for a viable East Timor policy it could sell at home and abroad, yet one that would preserve Indonesian rule of the former Portuguese colony.

On this latter point, the Howard letter was explicit: ‘It has been a longstanding Australian position that the interests of Australia, Indonesia and East Timor are best served by East Timor remaining part of Indonesia.’

To its architects in the Canberra bureaucracy, the ideas contained in Howard’s letter offered an elegant means of reaching that goal: direct negotiations with the East Timorese leadership, a long period of autonomy under more enlightened oversight from Jakarta, and an eventual act of self-determination.

Although even a delayed act of self-determination clearly contained risks, the presumption of the Canberra officials, almost certainly mistaken, had to be that Indonesia could convince the East Timorese they were better off remaining part of a bigger state. The alternative is that a fundamental contradiction lay at the heart of the letter between its proposed objectives and means.

The choice of analogy used to illustrate Howard’s proposal would turn out to be unfortunate. His letter suggested Habibie might emulate the 1988 Matignon Accords, in which France agreed to give its Pacific colony, New Caledonia, a referendum on independence a decade after implementing new development policies and political concessions to appease indigenous Kanaks. (The vote was later deferred by popular assent.)

In a typically animated meeting with Australian ambassador John McCarthy on 22 December, Habibie bridled at the notion of Indonesia, a former Dutch colony, being equated with colonial France. He dismissed the idea of a Matignon-style process as a ‘time bomb’ for future presidents.

The possessor of an inspired but impetuous mind, Habibie sat up late one night in January 1999 and scribbled a fateful message in the margins of his copy of the Howard letter. In a rambling statement that would become the basis of Indonesian policy, Habibie advocated an early referendum in which the East Timorese might ‘be honourably separated from the unitary nation of the Republic of Indonesia’.

Nine months later, having weathered a campaign of military-orchestrated dirty tricks and violence, the East Timorese overwhelmingly voted for just that. Australia’s hopes of cleverly engineering Indonesia’s permanent incorporation of East Timor had failed.

By then, Howard and his foreign minister, Alexander Dower, claim to have been converts to the cause of independence. That might be so, but it ignores the reality that from January onwards they were captives of a process of Habibie’s design. Australian officials were astonished by Habibie’s decision to announce an immediate referendum in 1999. Thereafter, they were left scrambling to catch up with events on the ground.

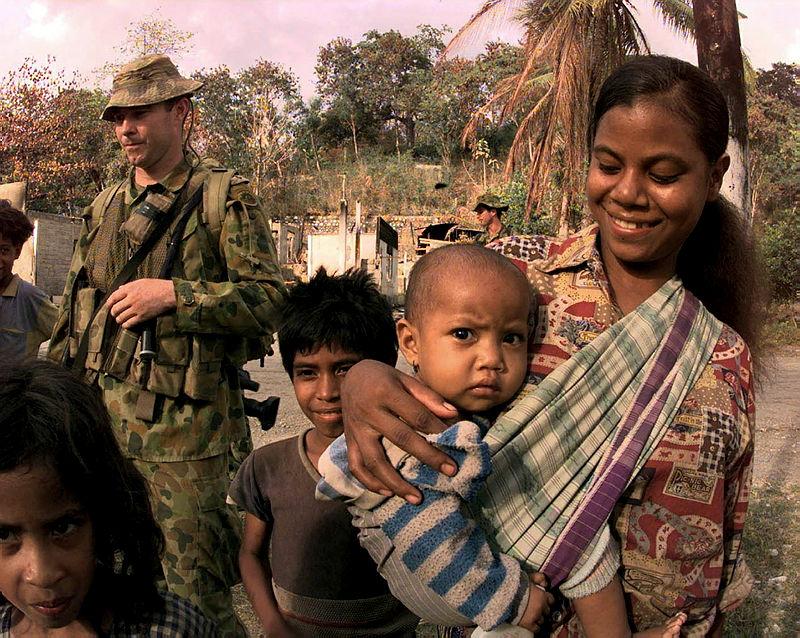

The vote for independence, the mayhem that followed and the deployment of the Australian-led International Force East Timor (INTERFET) could not have been envisaged at the time the Howard letter was drafted. Indeed, planning for a large security intervention was done in a rush.

It is hard to believe Australia would have chosen to intervene with its own ‘solution’ in a direct communication from Howard to Habibie had the consequences been fully appreciated.

For officials in Canberra who are required to think strategically, the result of the East Timor diplomacy has to be judged on whether it served a narrow definition of Australian national interests.

Its biggest legacy was the creation of a small, weak, aid-dependent state, vulnerable to foreign interference, and located 700 kilometres northwest of Darwin. To put it mildly, this was not their preference, regardless of any sympathies they felt for the East Timorese.

Another legacy was the creation of a new layer of distrust in relations with many in government and the army in Indonesia that would linger for years, hampering cooperation on a range of bilateral issues. It fuelled the intractable suspicion that Australia has designs on the liberation of the Papuan provinces.

On the positive side, East Timor started to fade as the constant irritant it had been in the relationship. That might have been one goal of the Howard policy, yet its eventuality looks like an accident.

What can we learn from Australia’s East Timor diplomacy?

First, we should remember the value of consultation. Canberra took charge of the substance and form of the policy. The process would have benefited from greater inclusion of the people Australia deploys at vast expense in its diplomatic mission in Indonesia. Surprisingly, it appears Canberra deliberately chose not to ask McCarthy for his views when the letter was drafted.

We will never know whether the quiet airing in Jakarta of Canberra’s policy change before it was presented to Habibie would have steered the debate in a favourable direction and avoided the impulsive charge to a referendum. When McCarthy was finally included in the loop, officials in Canberra even urged him to exclude foreign minister Ali Alatas for fear he would veto Howard’s proposal. This was short-sighted. It disregarded the value of giving officials on the ground leeway in policy implementation.

The haste to get the letter in front of Habibie put the fate of Australian policy almost entirely in the hands of an unpredictable president without the tempering influence provided by his own foreign ministry.

Subsequent episodes in the bilateral relationship show that the lessons are easily forgotten. Julia Gillard’s kneejerk live cattle export ban and Scott Morrison’s untidy speculation about moving Australia’s embassy in Israel to Jerusalem before he had an actual policy on it are two examples where laying the groundwork in Canberra and Jakarta can save a lot of unnecessary grief.

Diplomacy is not foreign policy; but foreign policy without diplomacy—the ‘application of intelligence and tact’ to the conduct of interstate relations—runs the risk of being self-defeating.

This points to a second lesson. When politicians start measuring the success of foreign policy by the likely reception it receives at home they increase the risk of causing trouble for themselves abroad. It is never an easy balancing act, but too often it tilts in favour of domestic gratification.

The conduct of East Timor policy, by a government that had just lost the popular vote in a federal election, was heavily influenced by how it would play at home. The live cattle ban, as much for the way it was done as the substance, still rankles in Indonesia; the Israel embassy move never happened but it delayed the signing of a trade deal for several months. Both were heavily influenced by domestic imperatives.

Thirdly, whether we are celebrating success or managing the consequences of conflict, Australia benefits from adopting modesty and restraint in its public positions, not just with Indonesia but in the immediate region. Howard’s assumption of the mantle of ‘war leader’ after the deployment of INTERFET, and the triumphalism that followed, rubbed salt into Indonesian wounds and delayed the necessary reconstruction of ties.

It was in the mustering of international support for INTERFET when the Australian government could recover some initiative. It deserves praise for how well it went about that difficult task.

But even as INTERFET was deploying, Australia needed to have an eye on the post–East Timor security relationship with Indonesia. To their credit, a number of generals, diplomats and officials did; the same could not be said of the politicians. Its importance was soon apparent with the arrival of refugee boats and the Bali bombing.

This lesson still hadn’t been learned in 2013 when Tony Abbott adopted a combative tone in parliament in response to revelations from Edward Snowden that Australia had bugged Indonesian public figures. It ran contrary to the best advice Abbott received and unnecessarily prolonged the fallout.

The Howard letter is now a historical artefact remembered by fewer people on both sides of the relationship. Yet it was one of the most decisive interventions in the history of one of Australia’s most important relationships. Despite attempts by some of those involved to retrospectively claim it was a success, it failed on its own terms. We should not forget what went wrong.